Modern machinery is an irreverent upstart god, mocking the Father’s ubiquity and spirituality. The silicon chip is a surface for writing; it is etched in molecular scales disturbed only by atomic noise, the ultimate interference for nuclear scores. (Haraway, 1985)

In 1985, Donna Haraway wrote A Cyborg Manifesto, introducing the figure of the ‘cyborg’ into the canon of technology theory. It set an intentionally ironic tone in order to combat the politics of a rising technological world order. Haraway foresaw how microelectronics would transform society and usher in a “New Industrial Revolution”. Rather than oppose new technology, as the Luddites resisted the power loom, Haraway embraced and integrated circuits with the concept of the human and nature. Haraway hoped for the cyborg to represent utopia, but today it is an instrument of techno- capitalism. As Haraway herself stated, “by the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism” (1991). This essay is an anthropology of the now-living cyborg.

Technology, the enabling force behind our cyborg present, can be traced back to the earliest origins of our species. As early as 3.3 million years ago in East Africa, Australopithecines began to manufacture stone tools. In the millions of years since, the forces of nature expanded our brains at the expense of our bodies' physical strength. This cognitive preference led to our mastery of fire, the birth of language, and the development of spears, clothing, agriculture, writing, and industry. Each successive advancement opened up new resources, territories, continents. They are our species’ solution to cold nights, hunger, and hyenas. At each stage, humanity was “reconstituted anew” (Verbeek, 2005). What emerged was Homo sapiens. Our technological inventions are both the product of and precursor to our success as an organism. To be human is to be technological.

Fast-forward a few eons, and the digital revolution arrived like the invention of a new fire. This started again the process of reconstitution. Over the course of this change, once-revolutionary technology becomes second-nature, and disappears into the background of human consciousness. In doing so, humans becomes blind to the tools themselves. Martin Heidegger describes this as ‘Enframing’ (Gestell), a concept where technology organizes the world around us, shaping our perception and experience (Heidegger, 1982). This process is notable in the birth of the ‘digital native’, a generation that grew up on the Internet. Millennials and Gen Z eagerly adopted new technology during childhood, a period of noted neural plasticity and identity formation. The Internet was absorbed into their understanding of the world, and they came to experience life through screen and sensor by default, increasingly unquestioningly. This adaptation is not a bug—it’s a feature of the human ‘program’. And so they might be considered the first-generation of true cyborgs.

Cyborg Evolution

If we are to become something new, there must be a process by which we get there. The process is evolution. Our progress as a species has removed us from the known pressures of natural selection, or so we thought. We certainly don’t expect to evolve as we once did. However, we are still under a great deal of pressure. Stress, crowding, sedentary life, processed foods, microplastics, and electronics are just a few of the environmental pressures in our cyborg evolutionary environment. Our fitness is now being tested against them.

It’s well known that chronic environmental, dietary, and social stressors activate different parts of our genes. However, it was previously unthinkable that these traits could be passed onto offspring, which is known as epigenetic inheritance. Recent studies in mice provide direct evidence for this newly discovered form of inheritance, and have brought about a complete reversal in scientific opinion (Fitz-James and Cavalli, 2022). If sedentary twenty-first century life is causing our bodies and brains to behave differently, it’s possible those changes might be locked into heritable genetic code.

Gene-editing technology enables humans to modify our own programming, the final form of cyborg evolution. CRISPR-Cas9 earned a Nobel Prize in 2020 and in November 2023, the United Kingdom approved its use for curing sickle-cell disease. If gene-editing techniques are applied to human embryos or a special class of reproductive “germ cells”, those changes become heritable. The consequences are so clear as to not require explanation. It no longer a question of if, but when, this technology becomes a feature of modern medicine.

More classically, the social conditions of society may act as an evolutionary pressure. This is known as ‘dual inheritance theory’ (DIT). Example may be found in dating apps. In this environment, sexual signals are flattened into lists of easily communicable traits. Engineers and data scientists control exposure to potential matches through proprietary algorithms which are unlikely to be optimized for compatibility. This effectively places private companies and their machine learning models in control of the reproductive population.

We have created a new evolutionary environment made up of digital, networked technology. We do not exist separate from nature, rather, we are nature ourselves, and our natural state is not static. We are constantly evolving. A thousand years passes in a short time, and there are consequences borne by the conditions of the past, present, and future on the human genome. The implications of this lend a new seriousness to the decisions we make as a society. Future generations might find that constant LED screen use and chronic sedentarism bring about epigenetically inherited adaptations. Or, digital habits might form the basis for human sexual preferences (see: iPhone v. Android preference). When we are the masters of our environment and its pressures, and wield the resources and power to change them, we choose what we become. A generation of social-technological interference could alter human genetics forever.

Adaptation on the ‘Postmodern Savanna’

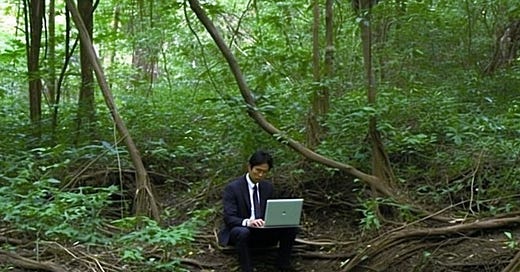

Adaptation to a changed environment is not a fun experience for most members of a species, and often leads to extinction. Within an individual's lifetime this entails struggle and stress. This pressure gives rise to increased competition, new behavior, and genetic adaptation over the long run. Necessarily, some individuals, if not many, will fail to adapt. We are adapting to a high-technology evolutionary environment. The savanna hypothesis once suggested that human ancestors began to walk upright because their forest homes gradually turned into open savanna. That savanna is virtually recreated in the Internet, requiring a new, digital locomotion. To make an inventory of the frontiers of our digital adaptation, we must address the tools that have come to dominate our lives.

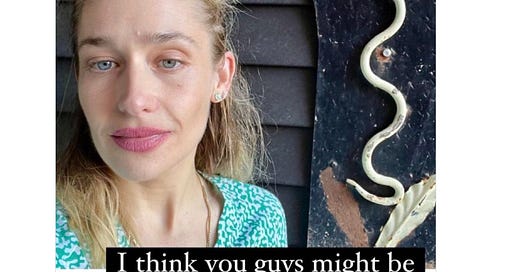

The use of smartphones and computers is subtle, refined, even fun, but paradoxically punishing and socially destructive. It is a quiet labor of repetition and fine motor coordination, and it takes place in relative isolation. Our physiology and psychology are not well-suited for the demands of this lifestyle. Studies show that smartphone, social media, and internet use are causing widespread psychiatric dysfunction. In May 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General declared a loneliness epidemic, stating that "even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately half of U.S. adults reported experiencing measurable levels of loneliness." Isolation and social alienation foment radicalism, especially among youth, and facilitate their withdrawal from society. Heavy users of digital media are twice as likely to commit suicide (2019). Repetitive stress and ergonomic injuries run rampant; cellphone use increases nerve strain by 70%.

In this environment the space for our own existence and quiet contemplation has shrunk, resulting in a “habitat loss” of selfhood. Financially profitable network media disrupts our social biology, which are fine-tuned towards kinship, reciprocity, and normativity (Richerson and Henrich, 2012). The Internet has expanded the local into the universal, which McLuhan named the ‘global village’ (1964). With access to countless unrelated individuals—impersonal, competing, contradictory—our ability to establish and conform to any group’s value-system is short-circuited. This dissolution creates immense pressure to compete for prestige. The loss of key social requirements destabilizes our ability to form secure identities and strong community bonds. Dangerously, these effects are socially invisible with the potential to snowball into disablement, self-destruction, and antisocial behavior. This emergent economy of information and image presents a mass crisis of identity and social developmental disorder.

Futureproofing H. sapiens

We cannot go back ideologically or materially. It’s not just that “god” is dead; so is the “goddess.” Or both are revivified in the worlds charged with microelectronic and biotechnological politics. (Haraway, 1985)

The habitat of the contemporary cyborg is of repeat technological revolution in a ‘ratcheting-forward’ action. Exponential growth in processing power (Moore’s law) in combination with snowballing capitalist accumulation has subjected all of us to ceaseless ‘disruption’ as proselytized by Silicon Valley venture capitalists. Opportunistic young entrepreneurs rapidly fill voids in the socio-political economy susceptible to digital innovation, which skirt around regulations and unions and baffle elderly politicians. Smartphones, computers, Internet communications, and associated apps initially arrived as luxuries. Now, they are more than manufactured needs, indeed they are social requirements, having replaced nearly all pre-digital human social functions. Society would collapse without behemothic cloud services which power everything from large- scale agriculture to international trade to government.

As new generations are born into the Information Age, ever more essential aspects of human social and productive life are transferred into cybernetic systems. A generation of children are being raised on iPads. They do not recognize life without capacitive touchscreens. These screens mediate all of cyborgian private and public life, transforming our senses and sensibilities. Opting-out is maladaptive, but opting-in leads to psychic and physical debilitation. This is not just ‘capitalist realism’, this is ‘technological realism’. Marxism in response states that the fault lies entirely in the capitalist mode of production. Any hope of revolutionizing social relations, however, is challenged by digital technology’s real and totalizing subsumption of the activities of life. The technology of the twenty-first century is qualitatively different and fundamentally inescapable than the factories of Marx’s day. Critiques of capitalism must include a critique of the technological conditions it has brought about.

We live in a rapidly closing historical window when the new political generation can still remember – if barely – a time before digital technology. We must develop hybrid frameworks which are able to analyze the complex relationships between technology, society, economy, and biology. Without doing so, techno-capitalism will literally write itself into the double helix.

References

Fitz-James, Maximilian H., and Giacomo Cavalli. “Molecular Mechanisms of Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance.” Nature Reviews Genetics 23, no. 6 (January 4, 2022): 325–41. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-021-00438-5.

Haraway, Donna J. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 1991. Heidegger, Martin. The Question Concerning Technology, and Other Essays. Harper

Collins, 1982.

Jiang, Shui, Lynne Postovit, Annamaria Cattaneo, Elisabeth B. Binder, and Katherine J. Aitchison. “Epigenetic Modifications in Stress Response Genes Associated With Childhood Trauma.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 10 (November 8, 2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00808.

Kapp, Ernst. Elements of a Philosophy of Technology: On the Evolutionary History of Culture. U of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Lieberman, Alicea, and Juliana Schroeder. “Two Social Lives: How Differences between Online and Offline Interaction Influence Social Outcomes.” Current Opinion in Psychology 31 (February 2020): 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.022.

Marx, Karl. Capital: Volume I. Penguin UK, 2004.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Createspace

Independent Publishing Platform, 2016.

Pigliucci, Massimo, and Gerd B. Muller. Evolution, the Extended Synthesis. MIT Press, 2010.

Richerson, Peter, and Joe Henrich. “Tribal Social Instincts and the Cultural Evolution of Institutions to Solve Collective Action Problems.” Cliodynamics 3, no. 1 (n.d.). https://doi.org/10.21237/C7clio3112453.

Saito, Kohei. Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism. Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Scharff, Robert C., and Val Dusek. Philosophy of Technology: The Technological Condition: An Anthology. John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Verbeek, Peter-Paul. What Things Do: Philosophical Reflections on Technology, Agency, and Design. Penn State Press, 2010.