Stephanie Yue Duhem (IG) (X) is a writer based in Austin, TX.

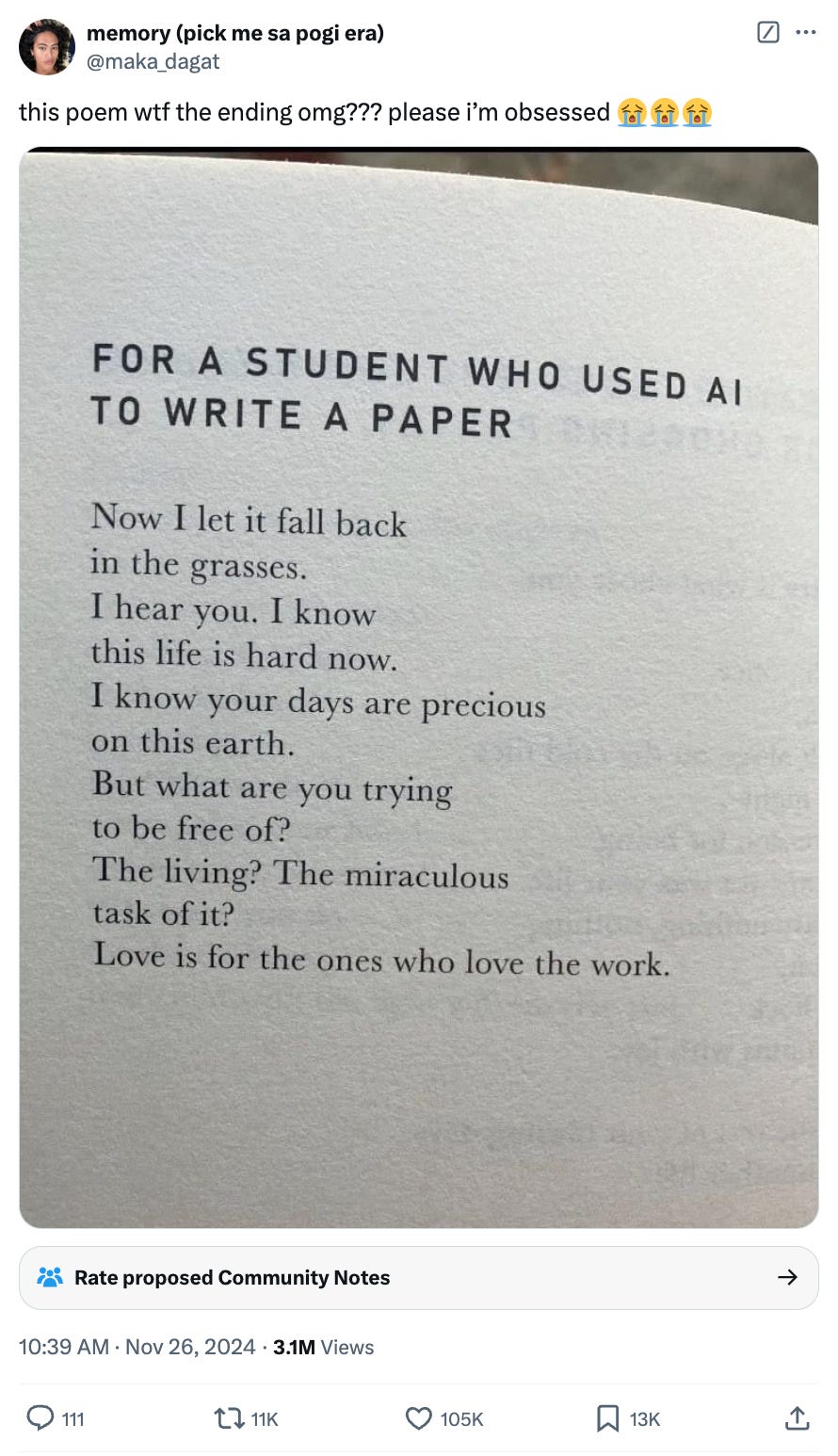

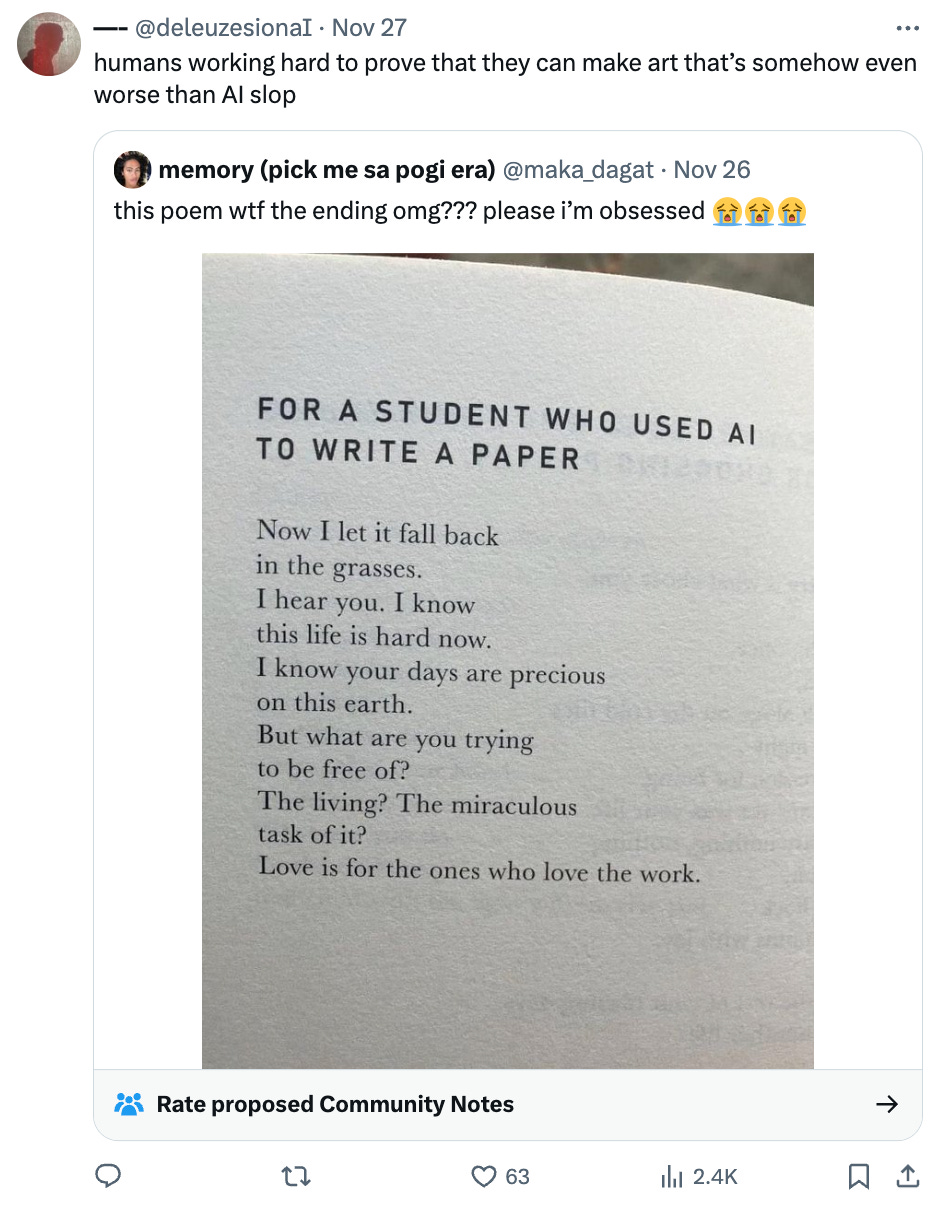

It all starts with a photo on my timeline: a page of lightly stuccoed paper, uneven lines of text cascading across its surface like fault lines before an earthquake. Before I even read the poem, I notice the metrics. Thousands of likes—accompanied by a quote-tweet count climbing to menacing heights. The tremors are starting. Between academic literary Twitter and basic poem-enjoyer Twitter; between leftist, liberal, and right wing Twitter; between zoomer, millenial, and boomer Twitter; the tectonic plates of contemporary poetry discourse are about to collide.

"Only bad poems go viral”—a statement bandied about in my own friend group—is maybe too facile of an observation. But it’s true that the qualities which make a poem catnip for one fawning segment of readers inevitably render it an object of derision for another. Moreover, this polarizing effect isn't random. Certain poetic traits act as reliable catalysts for virality, triggering an algorithmic reflex of appreciation and backlash.

What makes certain poems such efficient engines of discourse? And what does our collective obsession with dunking on contemporary poetry reveal about our relationship to art in an age when even our most intimate aesthetic responses are mediated through social platforms?

—

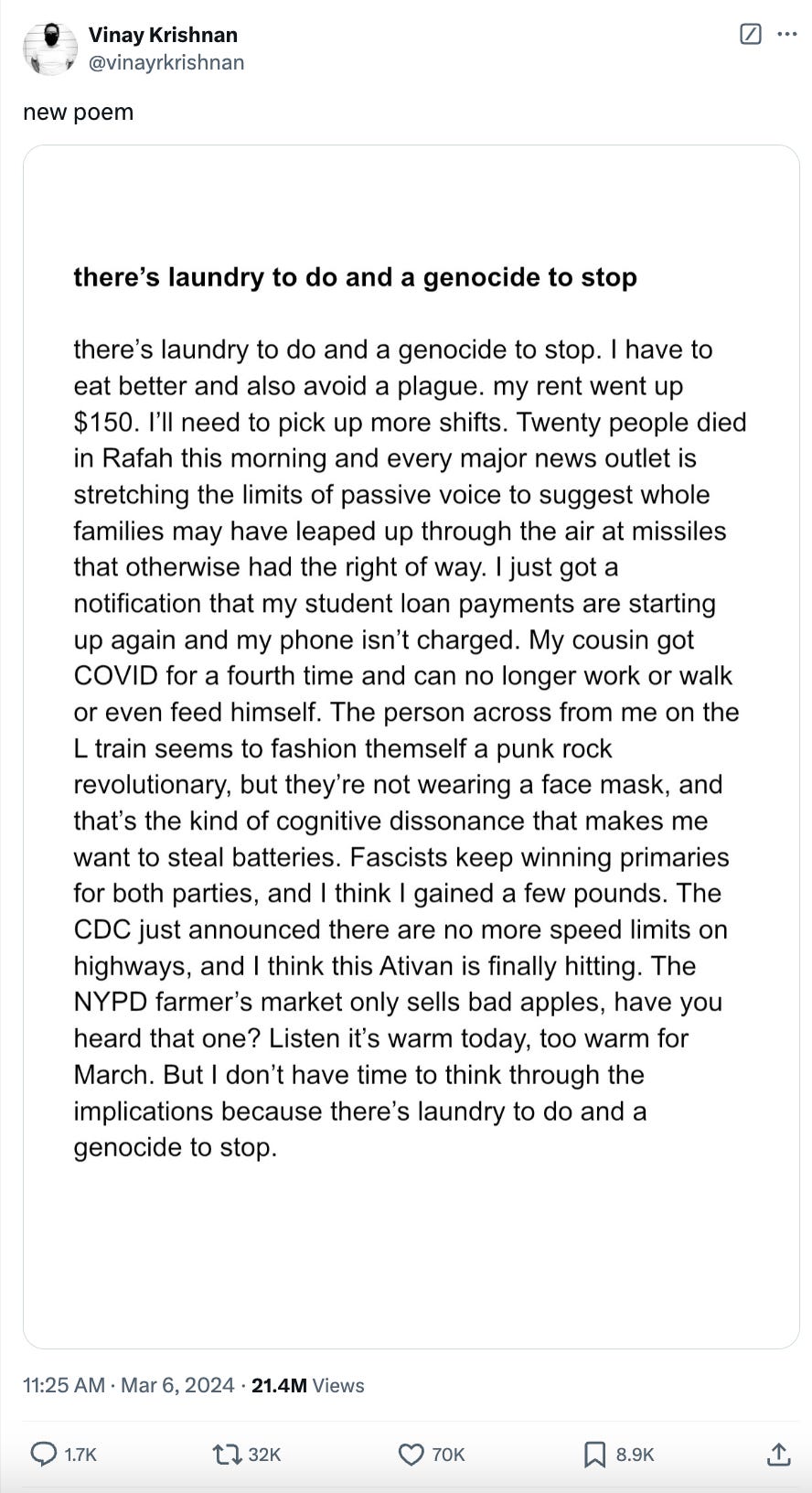

Consider three poems which achieved viral infamy in 2024: Joseph Fasano’s For a Student Who Used AI to Write a Paper, Vinay Krishnan’s there's laundry to do and a genocide to stop, and Amanda Gorman’s This Sacred Scene.

At first glance, these poems seem to have little in common beyond their ability to generate hot takes. Written in distinct styles by poets of varying identities, each poem addresses different topics and themes. Yet each is built according to a shared architecture of virality—specific traits that prime poems for both mass appreciation and savage critique.

These elements include:

Mixing Mundanity with Profundity

Discourse-triggering poems often juxtapose everyday objects or experiences (prescription drugs, smartphones, pop culture references) with weighty emotional, philosophical, or political issues. While some find this technique clever or compelling, others see it as obnoxious or trivializing.

Deploying a Contemporary Form

Talky free verse, prose poetry, or spoken word—while seemingly accessible—can also upset readers whose major exposure to poetry was through high school English. The absence of traditional markers they studied in class, like end-rhyme or meter, becomes instant evidence that something is “not real poetry” for this perpetually precocious crowd.

Signaling a Political Ingroup

Viral poems often align themselves with particular ideological communities, guaranteeing sharing from within the group and immediate backlash from the outgroup. The poem's artistic merit then becomes secondary to its function as a tribal signal—"good" poetry affirms one’s stance, while "bad" poetry is the opposition’s propagandistic slop.

Urging a Moral or Therapeutic Takeaway

Another common trait is building to an explicit lesson or revelation at the end, usually about sociocultural change or personal growth. While some readers will share these poems as vehicles of inspiration or validation, others resent the presumption and heavy-handed “self-help” vibes.

Being “Cringe”

Relatedly, poetry that delivers sentimental tropes with complete earnestness often draws praise from readers who prefer emotional directness, alongside ridicule from those who value originality or self-aware restraint.

Kindling Generational Divides

Finally, boomers might see profundity where Gen Z sees cringe, or vice versa, creating perfect conditions for cross-generational warfare.

—

Let’s take a closer look at these elements in a couple of the aforementioned poems.

Though not explicitly political, Joseph Fasano’s “For a Student Who Used AI to Write a Paper” manages to trip every other viral discourse wire.

Mixing mundanity with profundity (homework and grading with the miracle of life)—check.

Deploying a contemporary form (talky free verse)—check.

Urging a moral or therapeutic takeaway (life, love, labor)—check.

Being “cringe” (well…)—check.

Kindling generational divides (pre-LLM nostalgics versus younger pragmatists)—check.

The reprisal was not only unsurprising, but algorithmically determined.

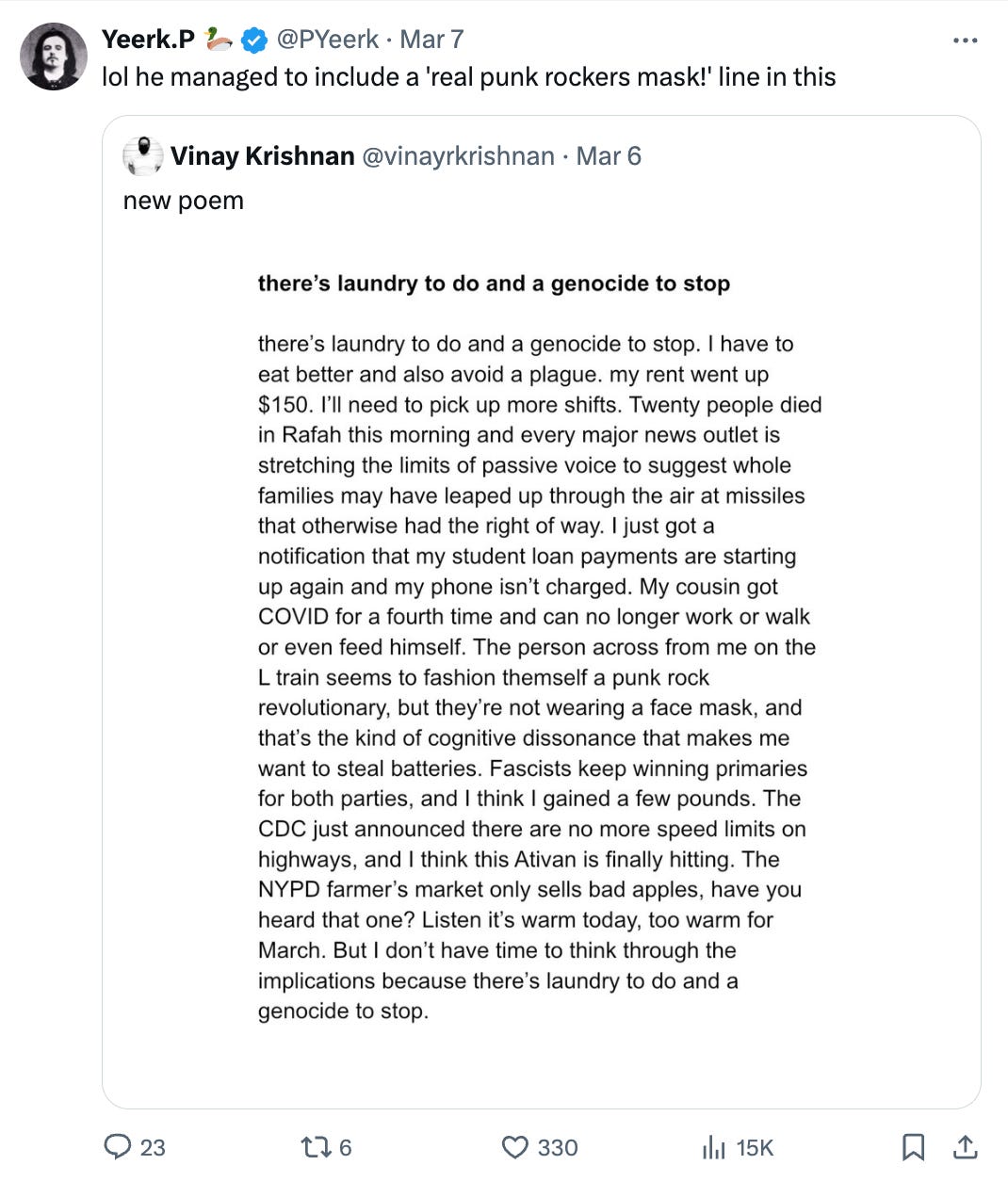

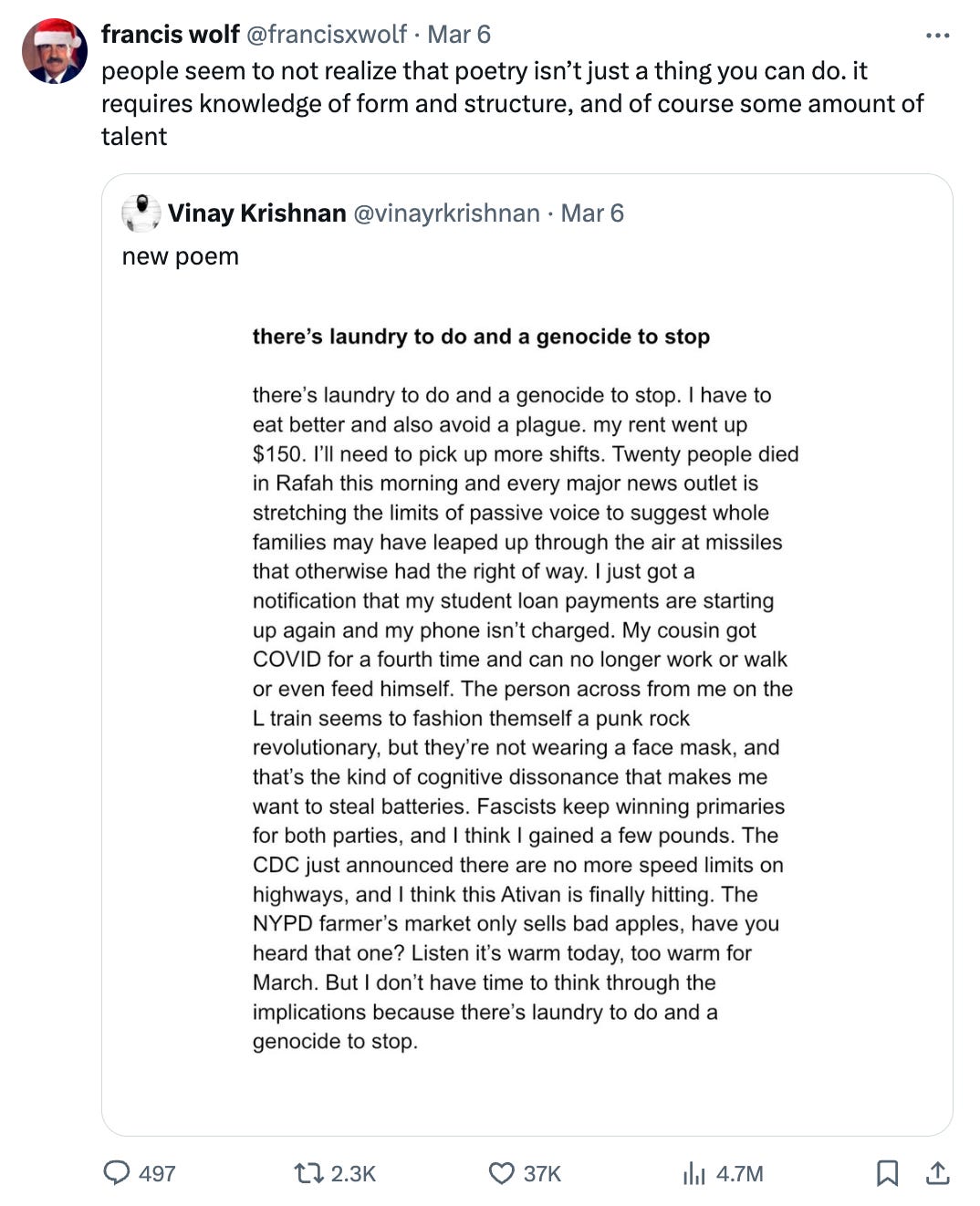

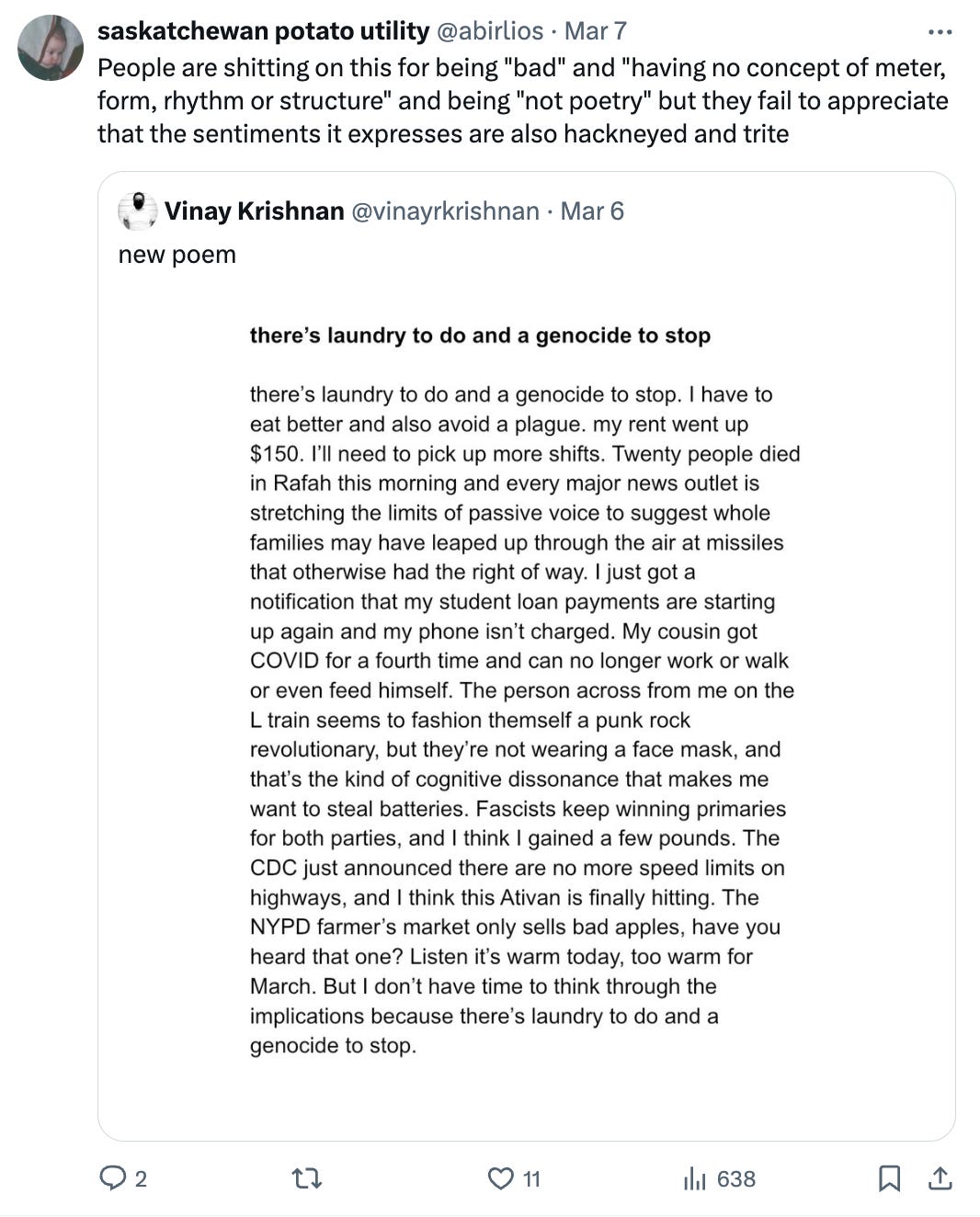

Similarly, Vinay Krishnan’s “there's laundry to do and a genocide to stop” flips every viral switch, including the political one.

Given Twitter’s ecosystem of political sub-sub-subcultures, the poem drew inevitable fire from left, liberal, and right wing factions—

—on top of the typical grumblings about style and sentimentality.

Overall, the predictable reception of these poems—from the initial surge of earnest shares to the ensuing wave of mockery—demonstrates the reliability of the poetic triggers I outlined. By hitting all or most of the six elements, these very different poems traveled identical trajectories across Twitter’s landscape, accumulating approval and disparagement in a mechanistic pattern.

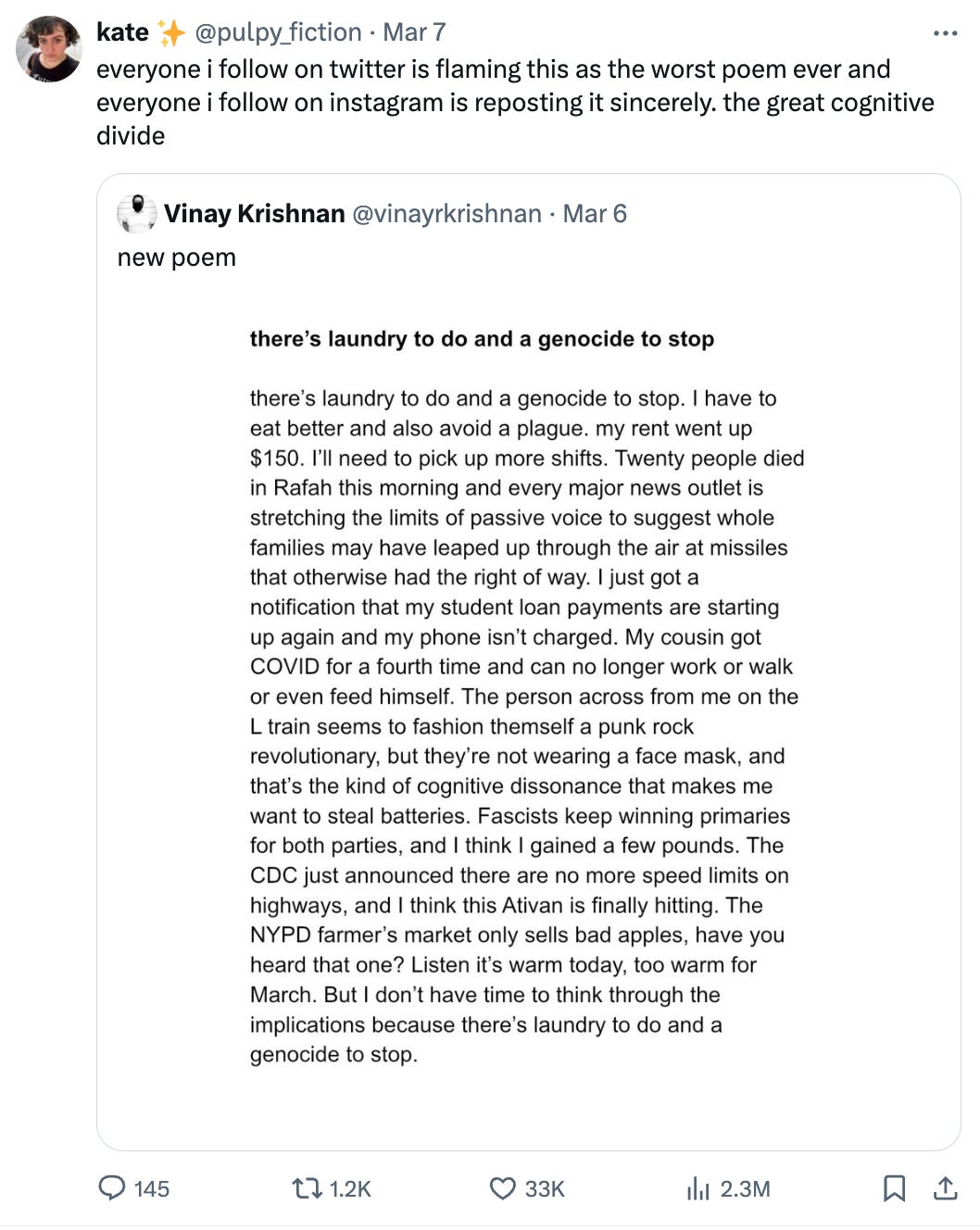

One caveat: the six triggers are, importantly, specific to Twitter. On Instagram—where a poem might pop up accompanied by a coffee cup or pen artfully in frame, as well as watercolor or pen-and-ink illustrations—even terrible verse rarely provokes vitriol. This stark difference suggests our relationship to art is increasingly shaped by the architectural affordances of the social platforms where we encounter it. Twitter's quote-tweet function practically begs for cutting commentary, while Instagram's visual emphasis encourages looking, if not reading. Neither is ideal.

—

Today, we engage with poems less as aesthetic objects worthy of sustained attention, and more as convenient units of online discourse. This shift becomes even more striking when we consider the material reality of poetry readership. While viral poems rack up hundreds of thousands of likes and shares, only about 3 million poetry books are sold annually in the United States—a fraction compared to the 189 million adult fiction books and 289 million adult non-fiction books sold per year.

The disparity between poetry's online virality and its actual readership isn't coincidental. Poems are, in many ways, the perfect vehicle for social media engagement. Their brevity makes them easy to consume in a single glance. Their self-contained nature means they can be completely divorced from context. Their formal qualities provide instant fodder for judgment. A novel might require hours of sustained attention to form an opinion, but a poem can be considered and dunked on in seconds.

What's lost in this shift from private contemplation to public performance is the slow work of developing aesthetic judgment. Few of Twitter's most vocal posters spend time reading contemporary poetry collections, attending readings, or tracing the evolution of forms. Instead, they encounter poems as random units of content in their feeds, stripped of historical context and artistic lineage. Their reactions are less about the poems themselves and more about participating in the platform's algorithmic cycle.

So maybe viral poems are not (only) inherently bad—maybe virality itself corrupts our ability to engage with poetry. In our rush to signal our tastes and allegiances through takes, we've forgotten how to sit quietly with a poem, allowing it to work on us slowly, mysteriously, beyond the metrics of social validation.

—

Thank you to August Smith, Wallace Barker, Noam Hessler, Tom Will, Anna Krivolapova, Hayden Church, Paul Franz, and Pierre Minar for a discussion that informed some of this essay.

yay steff

im so glad I found this! it articulated so well something else I was beginning to explore in a piece of my own. I loved yours and it helped me finish mine, so thank you very much for that.

here it is if you'd like to read it.

https://ellastening.substack.com/p/quotes-ive-seen-reposted-on-social