I. IN SEARCH OF METHOD

II. PANDEMIA: AN ASYNCHRONOUS CASE STUDY (APPENDIX A)

I Have So Many Wishes Inside Me

If I Muck Up it’s Only the World Watching

It Would Be A Dream That Had Never Been, That Would Come True

We’ll Find As We Go I Suppose

III. THE PRODUCTION OF ASYNCHRONY

The Meter and the Milieu

The Absolute of Relativity

Global Cybernetics: Computations of Repetitive Corollaries

The Gregorian Protocol

The Arbitration of Asynchrony

IV. FEAR OF MY OWN SHADOW: THE ASYNCHRONOUS APPARATUS

AND THE POLICE FIRST STATE

Datum Immensity

The Asynchronous Apparatus

FOMOS (Fear Of My Own Shadow)

From Police State to Police First State

V. ASYNCHRONY AND CINEMA (OR, HOW I FORGOT THE FUTURE)

Locating Hauntology (Cinema Without the Cinema)

Node 1: The Emergence of Time

Node 2: The Madness of Time

Node 3: The Failure of Time (The Production of Asynchrony)

VI. ASYNCHRONY AND CLIMATE CRISES

VII. TERRORISM AND SYNCHRONIZATION (GENERAL INTEREST EXTREMISM)

Anarchism and Kaczynski’s Acolytes

Neo-Luddism

Accelerationism, Leftism, Ecofascism

Cyberterrorism, Conspiratorial Episteme, Critical Infrastructure

“General Interest Extremism”

Conclusion

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I. IN SEARCH OF METHOD

I write of a ‘politics of time’; indeed, of all politics as centrally involving struggles over the experience of time. How do the practices in which we engage structure and produce, enable or distort, different senses of time possibility? What kinds of experience of history do they make possible or impede? Whose futures do they ensure? These are the questions to which a politics of time would attend, interrogating temporal structures about the possibility they encode or foreclose, in specific temporal modes.

– Peter Osborne, 1995

There are so many infinities. From Xeno, an enduring and fundamental paradox, one can never articulate the complete motion of the material universe–and for what would be the satisfaction of obtaining the asymptote? Laplace’s demon emphasizes our own integration into the object of our own measurement, the requirement of a sample size of infinite duration from which there is no possibility to grasp within a finite consciousness that attempts to measure inward. Yet materially, whatever happened, at what physics calls the beginning of time, there began a great explosive tumbling of particular infinite regress; I mean this in the material sense of “particular,” in that any body in motion embodies a particle. “Regress,” of the infinite, the all-powerful, all-knowing motion of all particular motion, the godhead, neither begins nor ends–yet endlessly collapses and expands as to the absolute limit and its infinitely dense opposite. The filament of creation unravels in eternally cyclonic spumes and recoils with the same reversal of fortune but in a duration of infinite negativity, an energy of unfathomable violence. When the perspective of the Moebius strip flips from expansion to contraction, imagine the quantum entanglement involved with an explosion\implosion of such density that, at once, it contains all matter and all motion in the known universe. From what love does the miracle of consciousness break through the quantum field in this violence? To what greater-dimensional timescale does the unity of consciousness owe? Paraphrasing Camus: You explain the universe to me with an image–you have been reduced to poetry. And what greater miracle could one encounter, in this horrifying abyssal maw, than poetry. To what desire or delight does this knowledge apply? The purest mediation. Already so many infinities clash inside of you. Fanged Noumena foolishly chased this to the end of time: “Why does the sun take so long to die?” You are searching for entropy when negentropy exists in equal measure as sought. The all-consuming fire of nihilism turns the insensible compulsion of knowing to ash–in such a paranoia, there’s nothing left to wait for but the world to burn. You cannot see the limits of the circuitry in which you attempt to measure. Yet I suffer a fate strapped to such calculations of decay (the fading of the light, the cesium atom, rates of profit). In use value, such entropy–when on the hunt–is nothing more than the calculation of repetitive corollaries. This one material dimension of time, that which we fascinate on as the functionally singular plane of terrestrial motion and thermodynamic dependence, is not a mystical phenomenon, but one of predictable attraction and repulsion. Consider the immensity of the timing systems of which we willingly avail–an unreasonably expansive and expensive system of coordination. Keyed in by the mobile market device, time is a free service: you are the exchange value, a particle in synchronization to a system bound to theoretically scalable infinite sets. The billions of years between now and then, the smallest atomic visions commensurate to the largest cosmic agitation–the same vital force drives all. But that force could not possibly be a material time, as nothing ever exists twice. The term “fourth dimension” is an erroneous application of interdimensional unreality to a particular material repetition. The mass consciousness of time severely underestimates its depth. The infinite series that is the universe we abide, and all other universes, must be conceived from infinite infinites: a plane of immanence without any characteristic because it cannot be perceived at the aspect of dimension we call duration; rather, this temporal regime of which we are subjected should be named extensity.

Presently, we maintain this singular dimension as an electric time: transmissions organizing social simultaneity, through rhythm, duration, and decay. The frequencies of these pulses derive from spatial departure and arrival of some external repetitious source and broadcast as symbols from centralized transponders to diffuse receivers. These broadcasted measurements, maintained through political alliances with science (often the invented universal, a trend not unnoticed by the revolutionary Daniel Bensaïd) are agreed upon in variations of communal, provincial, national, and international law. Concentrations of power arbitrate these agreements often in the terms of peace treaties, or after revolutions, unifying time to the sovereign within the realm, in order to expand the synchronization or configuration of simultaneity across an endlessly enlarging geopolitical space. This is not enough space, as more earnest discussions around interplanetary colonization imply an extraterrestrial time. Will “geocentric” soon replace “Eurocentric” as the next concern of the academic Left? Time can be considered easily from here (off-earth) in its most basic characteristics: the measurement of gradient between light and shadow in what we call the rotational planetary day, solar revolution through the year, earth’s axial relation in the seasonal, the sidereal monthly designation derived from viewing stars. These are terrestrial perspectives, including that problem in positioning constellations as a constant, confronted with more specificity in quantum perspective and the very construction of simultaneity as an error of judgment.

The current experience of time and space—the condition of asynchrony—threads totality together, in conditions of global precarity (a temporal phenomenon) and the refusal of international capital to relinquish the prospect of “growth” (an assumption of futurity). The developments of technics, strategies of power, economic revolutions, and cybernetics all inform the possibility of a new dimension to the potential of global timing systems. Asynchrony must be seen not only as a spatial-temporal experience, but also as a conceptual apparatus to reconfigure time, timing systems, rhythms of life, interdependence of alternative lifestyles, time as praxis. Asynchrony demands critique because it appears as a universal and at every juncture. The demands of current systems of production quite obviously breach planetary limits—even on the exchange level of microbes—and therefore stretch beyond time as we might fathom. Humankind’s broken covenant with nature reaches its punitive phase, pitting the Earth against the leviathan. Time levitates around concrete-abstracts depending on the broadcast and interpretation of visual cues, then used to condition systems of reproduction. Temporal experience arises from this broadcast and its use in the mode of intercourse. Attitudes to time reflect the organization of societies, yet societies shape time, radiating from power centers. Times then become cybernetic feedback systems searching an equilibrium, defined outside the system–uncontested against the dependency of its inner use. Commerce, wealth, and conflict force communities and nation states into regulation and full coordination of time scales, shifting from religious ownership to the alliance of the scientific and political, never acknowledging this outside, demanding a dyadic certainty by enclosing territory around expansive timing systems. Systems of domination retain the fictitious immutability of time and space, claiming time itself as the fundamental fiction conquered in the coordination of humanity. An interconnected global perspective beyond the inappropriately valorized notion of Relativity emerges. I suggest the current temporal regime is breaking down by computational excess.

In its simplest, time emerges from distinctions of light and dark, pulses of on or off, what a binary mechanism defines as I/O. Peter Galison notes: in the 1800s “Cambridge physicist James Clerk Maxwell had produced a theory that showed light to be nothing other than electric waves and so unified electrodynamics and optics.” Fundamentally, I see “time” as the appearance and evacuation of power. In the hands of the state, it is not the monopoly of corporeal violence, but a monopoly of synchronicity, a violence of a hauntological value—the future forecloses possibilities outside this temporality, by coordinating a social centerpiece appearing to have no politics. But that is the absent ideology of science through history, particularly when shielded in the rationale of pure physics. Where political interests lie or the foundation of a center of study with financial backing do not tell us enough. We must interrogate: What is the sovereign exception of the science that is produced under its domain? Which field abandons time? The church burned Giordano Bruno at the stake, in 1600, not for cosmology but for the required heresy of his infinite-yet-indifferent universe. “Your god is too small,” he told them all. The Vatican now maintains celestial observatories, in its various attempts to retain control of time—in particular the pagan cover-up of Christmas and its solstice antecedents.

Maintaining the project of consciousness is the wager—eliminating the space between the future and a future, the cognitive closure of alternate possibilities. We access time as a semiotic-material intermediary of theoretical physics, a concrete-abstract mediating interior and exterior coordination, a construction and projection of one framework of synchronization, put into symbolic broadcast and used to coordinate material flows. In the years since David Harvey’s The Condition of Postmodernity (1989) which contains a massive amount of reflection on the experience of time, GPS systems have become a global public utility, inducting individuals into satellite networks of large-scale military and commercial coordination; we now have one or two generations reared under the completed, publicized net of GPS—these satellites are simply orbital atomic clocks, towering above us in geosynchronous orbit.

The five scales of abstraction Harvey refers to, with examples inflected, as a general perspective of asynchrony: the individual, the ability to produce and subsume Reason disconnected from the flow of Reason of all other induction; the particular spatial-temporal, with time systems so consolidated the time system becomes a given; the general behavior of capital, perhaps asynchronous accumulation, not unrelated to what others call ambient accumulation; class division, where value sits in the proposition of asynchrony; and life in general, which can be seen as advancements in medicine or changes to the general experience of being, such as second-order consciousness that guarantees a synchronized core, the abstraction of humanity away from “natural” process. In the semiotic arc, the interwoven communication networks actuate asynchrony among the material flow. Bratton’s outline of The Stack is useful in its broadest framework. Here, it includes six layers: user (individual), interface (mobile market device), address (time stamp proof of work), city (coordination and contrast of time stamps), cloud (virtual space of information processing), and Earth. Holding this rudimentary-yet-complex sketch in mind should be sufficient to imagine the frame of reference in which the condition of asynchrony persists—yet the possible permutations of these two perspective matrices might require an algorithm in which to know the limits of asynchrony. Every layer and every permutation of this matrix accesses the same rhythms via freely available timing systems–every computational impulse depends on a simultaneity of a knowable comprehension that nevertheless could not be understood in totality, even when attempting to combobulate the cybernetics at which the entire machinery operates. The time of the timestamp contains a remarkable history of power and contradiction, crucial to every inflection. I suggest Paul Feyerabend’s “epistemological anarchy” with Chomsky’s anarchy in mind, in that the burden of proof in favor of time rests on those in its maintenance; the argument of this essay is that this burden is no longer met.

The condition of asynchrony must account for a circuitry of global simultaneity running throughout retailers, banks, production centers, distribution networks, treasuries, black and gray markets, naïve cultural exchange, calculated intelligence operations, central banks, a washed colorless propaganda that generates its own oppositions on autodactic biunivocal algorithmic discourse, channeled in all radii from the individual, commensurate to scalable infinite sets, prefiguring a system of capital that runs on an impossible-to-ensure future that is nevertheless predictable from an averaging of mediation and commodity delivery to the molecular org chart of these corresponding radii; the greater the archive of exchange to a greater degree the future can be conditioned into a presumptive kind, a self-organizing feedback loop of a certain temporal regime, requiring an ever-expanding maintenance of archive to further analyze repetitive corollaries. Capital haunts the past as it plans these futures, calculating buying habits of the mobile market device into a likelihood of what can be convincingly sold. What is the analysis of markets other than pattern recognition in difference-of-kind, distilled to the singular difference-in-degree of capital?

A strong motivation of the US first adopting Daylight-Saving Time in 1918 was to maintain at least one overlapping hour of financialization with the UK stock exchanges. The condition of asynchrony obviates this, as a robot delivers an anonymous short sell to a market in a time zone across the world three days from now, tempered by AI, the heraldic nonsense of insider trading erased by the technicality of global timing systems. In 1611, the corralled open-air Amsterdam stock exchange, the first of its kind, commenced under the aegis of a huge clocktower, in order to make trading securities more efficient. Following a shift in scale of capital from the Dutch to the English, the United States enlarged yet again. To what scale does the next hegemon shift? As the limits of spatial expansion are met, the solution seems to be a dislodging of time, an inward expansion to the polyvalent framework of asynchrony—the invisible disruption in the next era of capital expansion, where time can be exploited such that time collapses through computational excess of capital management. When all is subsumed, there will be nothing by which to measure outside this correlation of infinite sets. Georg Simmel, in The Philosophy of Money, discusses the tribal chiefs of Oceana, who could not even conceive of stealing, because everything already belonged to them.

Jonathan Martineau writes, “an analysis of time in contemporary societies gains from taking into consideration the development of capitalism as a contradictory social system.” Martineau tells us clock time takes on different characteristics after the advent of capitalism, that clock time, despite popular conceptions, is not a product of capitalist societies. We cannot flail from this outside but, rather, mold the boundary that redirects conditional flow, the procedure and product of algorithm, of which every node inflects influence. Time depends on an interior/exterior agreement. It is not the expression of relativism that sustains this, but the story of time as ritual, the guardians of this ritual inherited and applied. Foucault asks: “How is it that rationalization leads to the furor of power?” This reconfigures our perspective of time by mediating the relationship between rationalization and power, to reintroduce as false problems the elements of assumed temporal truth. In the triumvirate of Gilles Châtalet—cybernetics, politics, economics—the production of asynchrony becomes the structurally cybernetic model of time, in that its first order consolidates around an observed core, the second-order observation a condition of the atoms of distress. This is a story about the production of synchrony first, and then the elevated valence of the mode in question. That is to say, the condition of asynchrony relies on full synchronization.

First appears the élan vital, the vital impulse, that phenomenon imperfectly grasped by science, a sense of constant pulsation, giving life an unstoppable surge that cannot be captured or restrained in full measure. Vitalism and the quantum uncertainty effect, life as observed, blossom outside the “irreconcilable dichotomies that characterize modernity.” Henri Bergson obsessed over a continuity of a different kind than the maintenance of the temporal regime: duration, the heterogenous quality of dynamic real time, in which contextual margins collapse endlessly and escape measurement, the unstoppable and innumerable of the élan vital. Duration opposes extensity, the homogenous and fractured, the measured and quantified production of “time.” In Creative Evolution, the defining work of the élan vital, Bergson defined it as a retarding force that worked against degradation. It was “attached” and “riveted” to matter but not entirely part of it. Accordingly, living bodies were part matter—they were “riveted to an organism that subjects it to the general laws of inert matter.” But they “tried to rid themselves from those laws.” They “did not have the power to reverse the direction of physical changes, such as Carnot has determined them.” But they were nonetheless “a force that, left on its own, works in the opposite direction.” Incapable of “stopping the march of material changes, it nonetheless is successful at retarding them.”

What we must, then, insist on is critique that considers the work of Bergson, Schrodinger, Planck, Heisenberg, Bohr, and de Broglie, to what Sartre, in his own Search for a Method, his reconciliation of his existentialism with Marxism, remarked on as the “practico-inert,” the nuance of subjectification, and the necessity to take into account a kind of study that weighs the observer as a modifying aspect of the system—the absolutist Einstein refused to account for this, saying, “God does not play dice with the universe.” Latour characterized the aporia in slightly different terms in Reassembling the Social—maintaining the perspective of mediation that does not privilege human action. The negative hermeneutic must be weighed against logical positivism. To consider the opposition of the Marxists to Foucault—a devotion to the dialectic and Hegel’s philosophy of history—now arouses a line of questioning that asks: does the Marxian-derived critique of time insist on production and circulation, in a descriptive capacity only? Is this not a hyper-Newtonian metaphysics that presupposes time as absolute, homogenous, even if it is an absolute of the material, time as pure physics, pushed through industrialization? When Tombazos uncovers the varieties of time in Capital it is with the force of the Hegelian category of measure and the thesis-antithesis of Volumes I and II, to the synthesis of Volume III. If capital determines or relies on specific temporal modes, to what benefit does the extrapolation of these modes offer a resistance effort at the end of time—not in the sense of Foucault or Mill, civil society overtaking the state, but the end of sustained consciousness? A non-ideological reading of Capital builds a more efficient capitalist.

In cybernetics, timing takes a central position, the gauge by which the social-mechanical organizations of such approaches can be grasped. Early influences on cybernetic theory were experiments in which the structure of the human brain could be derived by the difference of neurological reaction times. In the supplementary book to the landmark Cybernetics, Norbert Wiener stated his thesis of The Human Use of Human Beings: “… society can only be understood through a study of the messages and the communication facilities which belong to it; and that in the future development of these messages and communication facilities, messages between man and machines, between machines and man, and between machine and machine, are destined to play an ever-increasing part.” How is the consolidation of time a feedback system of the social organism itself? The densities of populations and the division of labor inform the necessary configuration of simultaneity, which further necessitates further precision, which further informs the configuration of simultaneity, which allows for greater concentrations of populations, which requires further precision… until the proper micro-derived frequency can radiate in past the skull, broadcast to the pineal gland, and charge the single life with the rhythm of the social—the speed of broadcast through Relativity accounted for! Galison writes that at the turn of the 20th century, the era of Einstein’s emergence as the scion of a new physics: “Time coordination in the Central Europe of 1902-06 was not merely an arcane thought experiment; rather, it critically concerned the clock industry, the military, and the railroads as well as a symbol of the interconnected, sped-up world of modernity. Here was thinking through machines.” Similarly, Wiener’s cybernetics made time central and unitary, wherein he developed the “brain clock hypothesis,” in which he posited the human brain as nothing more than a timing device for processing information. This flattening of the milieu, individual, and machine to the same level reduces all to a temporal unity of extensity in an indifferent network of particle economics, and one that must be tuned to a universal standard—the universal standard of an extensity. As Henning Schmidgen recently commented on Wiener, “From the standpoint of cybernetics, these entities or ‘systems’ did not so much differ in essence, that is ontologically. The main difference among them was rather chronological—that is, it was tied to their respective temporal regimes.” The history of time consolidates these temporal regimes into a normative unilocular homogeny.

Wiener introduced an idea of time he believed would end the debates between mechanism and vitalism, by unifying interior and exterior synthesis. Yet he did believe the servo mechanism lived in Bergsonian time. The division of academic labor in regard to time allies it with serious study in the realm of physical science; time takes on an absolute character that tends to make fools of those in other disciplines after a certain juncture; this is not the first paper to suggest this rupture emerges between Einstein and Bergson,demonstrated further through the work of Jimena Canales. Norbert Elias, in an immense essay on time, saw its dualisms as representative of academization and knowledge production, excluding social sciences and philosophy from the mechanical aspects, forcing the topic on a “serious” or material level to the realm of theoretical physics. To excise the full potential of asynchrony, we might recover these splits in the order of an interdisciplinary approach. While Wiener’s could be argued as one version of this in his quest for an inner-outer mediation, his goal to transcend nuanced perspectives of the false problem speaks only to the strength of the temporal regime. He wanted to end discussions of time. We need theory in the vacancy of intersection, and so the current work is not one of mere curiosity, but of an attempt to venture through this absence of interdimensional thought.

Bergson and Poincare both argued that measuring time destroys it–the most polished razor leaves its residue, the most supple medium shedding its excess, the action itself excising the extensive from the durational. What we then discover is a plane of temporal immanence from which any manipulation of synchronization can be made. Before the revelation of quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle, Schrödinger’s cat, the observational effects of measurement on matter, et al, this concerns the mystery of continuity as much as science—the practico-inert, the phenomenological inheritance that limits the true actions of one’s freedom. We now understand this occurs in quantum measures and alter-states. How are we not to infer that time, being just one of these unseen (yet rather felt, intuited) dimensions, expels the patterns of behavior in observation? Better ways of planning by the measurement of the future are not dependent on the consolidation of the present. Any temporal society is a planned society. Time is essential and constitutive of a planned economy, with the GPS the largest social utility in history, benefiting less the viewer of it, and more those who make use of the measurements thereby viewed—and, in asynchrony, the analysis of this use. These are social measurements as much as they are scientific measurements, and they bridge a gap of understanding that needn’t necessarily arise from the perceptual. The other side of that bridge—the wager of simultaneity—is a wager of the heart. It arises from a good faith argument in defense of my fellow. To agree on next month is to agree on the invisible orb of right now. And here is the contradiction. Because the precision of broadcast time is not a purely social mediation, but an instrument of a rationalized science; we might ask to what extent this instrument no longer bears the burden of its legitimation. That is a vacancy of critique, a demand for uncertainty, the discomfiture that is outside the I/O, an application of affect theory to science studies itself.

II. PANDEMIA: AN ASYNCHRONOUS CASE STUDY (APPENDIX A)

I Have So Many Wishes Inside Me

One in every 153 US workers dawns the helm of the arborescent, a shrinking megafauna that now emits more carbon than it eats, a site of tropical ecocide, a mythic that consumes its own potential, a geolithic tragedy of the fall of one biological organism giving rise to a cybernetic inversion of its own disorder and demise: Amazon. These workers pee in bottles or defecate on strangers’ front lawns, in order to meet quotas derived by off-pace algorithm, calculated for a machinery of profit that exceeds the time scale, broaching an inhumane asynchrony. A worker in one fulfillment center had a heart attack, fell to his death, ignored on the warehouse floor for 20 minutes, coworkers dusting up their packaging quotas rushing by. As labor moved to organize, management countered just as quickly to its own information strike, propagandizing aggressive anti-union campaigns and digging up the old Pinkerton spies. The wiry clutter and radiating filth of the cyberpunk vision entered the firmament, establishment media posting headlines like “Amazon’s New ‘Factory Towns’ Will Lift the Working Class,” an image viral of a giant company warehouse surrounded by slums. Employees became aggressively monitored down to the second and the keystroke, alternating regulation of paranoia, leading the invasive surveillance to be dubbed by labor researchers a “panopticon.” Does the media hand us this language for the reason of folding into critical theory that somehow makes Foucault into a prankster? A pandemic swept the globe, and a worker at an Amazon fulfillment center in Detroit begged a battery of video cameras at a news conference to stop ordering the delivery of sex toys. He led a walkout among unsafe working conditions, in which many contracted this virus, and then he was fired. The gleaming head of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, not so unlike Foucault’s, later flew an ultra-phallic rocket ship to the edge of space, landed back on Earth, put on a cowboy hat (the headwear of the frontier, the protection applied post-coitus) and declared: “I want to thank every Amazon employee and every Amazon customer, because you paid for all of this." What kind of analysis is necessary here? They carve these monuments out of nothing, out of the empty promise of a myth that had never been. First, they erase the skies and then claim to travel beyond the stars that don’t exist.

The asynchronous laborer compounded the exploit in pandemia: thousands of “essential workers” risked life or fell to death to keep the engine of commerce burning. This “essential worker” designation set fire to the moral receipt of an economy dislocating to service jobs, in this case valorized by the necessity of porterage. The delivery drones had yet to be calibrated against the birds of prey who knocked them out of the skies. The state mediated the conditions of production by revealing the tolerably baseline laborers as the only real source of prosperity at the perihelion of simulacra. Isolated, we watched on screens as the elite engorged the journey to the middle. The ultrawealthy gained $3.7 trillion in wealth, while ordinary people lost an aggregate of $3.6 trillion over one year of pandemia (“probably just a coincidence”) an imaginary, virtual sum nevertheless representative of real brutality. Haunted by subsistence, paid to do nothing, the expression of consumption remained the universal exercise of individual control in an idle petty bourgeois, as the synchronized libidinal core could not be rocked from its nesting place in the global north, aligned to the Atlanticists’ stars. The individualist spirit of liberalism, so deep in mediated consciousness, rationalized the paranoia of lockdown, the service industries now asynchronous in their unlimited operation, invisible in their service, sterilized, hermetic; groceries, meals, consumer goods appeared on doorsteps as if left by helpful-but-probably-vengeful ghosts, the SEARS Catalog staffed from Kurosawa’s Dreams. The only self-assertion into this world was the codex: not everything we need, but anything we want, figments of lost hope cast into binary analyses. Consumer sovereignty ruled the exception, revealing the psychic violence at hand—a broken time scale, shocked into the truth of asynchrony, the urgency of the moment not disrupting the assurance of getting anything now.

This virus swept in, but the reproductive cycle required the continuity of the temporal regime. This depended on the education system distributing labor among its strata. At the teenage circuitry, New York City high school students attended classes from home, using video conferencing. A year of this went by and then the virus receded. Quarantine protections lifted, after the military administered vaccinations, and these same NYC students returned to synchronized spatialization—yet continued video conferencing. A few dozen students sat next to each other with one overseer administering discipline IRL, but the pupils corporeally in the schoolroom connected to different instructors, pulsed through the net device equipped on each desk. One student observing a physics lesson sat next to a student observing an English lesson who sat next to a student observing a math lesson, all concentrated in the space of the school, but constructing diffuse knowledge, centralizing students while dispelling instructors. This seems necessary only to reinforce the monopoly of space, unified by timing systems, the invisible hand of this investment power forced by pandemia. This corralling keeps New York the most segregated school system in the nation. And make no mistake, hardline broadband access itself is segregated, a redlining of cutting-edge transmission equipment from historically oppressed people. The silent laptop overseer in the example, if not for the imposed spatial necessity, knows the truth: the quality or content of education could be separated from the space in which truth and knowledge are constructed, a ratiocination of space from which institutions historically derive their power, a scaffolding of cybernetic maintenance constantly spidering out of archaic formations. Because the answer to the question, is education of a positive net worth? sidesteps just who determines the very measures of worth. The discipline of primary education tethers to place. The more pressing query is: of what use is the curriculum to operating in this world? Not, “What is it?” but, “Does it work?” Show one the chain of contingencies holding them up and they will be in no better a position as to fending off the wolves. To paraphrase a great philosopher, contradictions never killed anybody. Yet it is these contradictions that reveal the crossroads of determination. Here, it is the potential liberatory function within a racialized meritocracy, shown through a contradiction in the very proposition of space.

In pandemia, the knowledge economy boomed on. The divide between public and private times disappeared for the intellectual laborer, for the educator, for anyone lucky enough to work behind a laptop, while illuminating the truth of financialized, synchronized space: emptiness. “Globally, in the knowledge and technology industries,” Jodi Dean writes, “rental income accruing from intellectual property rights exceeds income from the production of goods.” The outdated necessity of an office dissolved, as the home wired to the web fully broke the privatized barrier of the mainstream workspace to continue this production of virtual, intellectual value—maintaining the power of asynchronous information overload. Relegated to the conditions of hermetic precaution, the web became somehow more crucial to commiserating this anti-social society. Workers in office administration, public relations, culture industries, and digital media especially—called depreciatively “fake email jobs” by those lucky to still have them, or what the late David Graeber might have called “bullshit jobs”—now untethered from the organization of clock time that synchronized spatially dependent work gatherings, posted to the internet the increasingly prevalent sentiment: “What even is time?” This was not a question of the philosophical or scientific type, but an irony-poisoned expression of the irrelevance of the clock, the suddenly fractured durational aspect of the calendar, and instantiations of the mobile market device.

A question once reserved for philosophers and physicists becomes a prevalent statement of psychic dislocation: “What even is time?” It cannot be answered because time has been dismantled, not in the sense of obliteration, but by constantly shifting centers away from collective notions of experience, constructions of historicity, and disengaged from space. In a rhizomatic potential, this should benefit a syndicalist development of honest, multitemporal variety, or an amodern decolonized time; however, the dictation of time and space as absolute in social reproduction makes minute synchronization compulsory to subsistence in the asynchronous marketplace—transmissions of time stamps of varying quality refracted through analytic algorithm of upward mobility, scalable radii of infinite set size. The mechanisms behind this information gathering are so pervasive and powerful, the US intelligence apparatus uses “ad blocking” software itself, so that compromising information might not be disclosed through targeted marketing, thereby becoming victims of the very open system exploited for national security ends. In a mechanism known as “bidstream,” data brokers hold “real-time” auctions for the placement of mobile market ads. In this, user data has already been collected. In one case, that data was purchased by the US Customs and Border Patrol, through an outsourced government contract, leading to the arrest and expulsion of immigrants. What are known as “cookies” themselves are a function of prosthetic memory of this apparatus, “saving” time by harvesting and storing market information in an archive, a memory of consumer function, a necessity presented in the violence of synchronization to keep pace with the machinery of accumulation and maintain the rhythm of market computation. Most internet interfaces don’t even function without the host OS synched to Greenwich mean time. Why? So that the timestamps sent in both directions can locate the device of access in space, using time (the legacy of longitude, a recent scientific-historical development) and so further generate relevant proximal data, while also maintaining the computational metric output of production cycles. Commodity production must have space in which to rationalize the abstraction of value, actual places through which capital can manage its flows. The kids must be kept in school.

In pandemia, skyscrapers and strip malls alike became vacant (what Fredric Jameson referred to as “zombie buildings”) towering and squatting reminders of the manifold precarities and contingencies of modernity (as described by David Harvey, himself inspired by Baudelaire) despite the asynchronous pathology guaranteeing the conditions of full network/supply chain activation (as described by Jonathan Crary) synchronized to such a degree that dis/engagement itself hides behind milliseconds. The rhetorical question (“what even is time?”) interrogates the obvious compaction and dislocation of time when valor cannot be derived from an immediate sense of self, where the established bias of communication fails, where temporal systems collapse under the force of pandemia’s cultural trauma. Because value emerges on the comparative level (as Marx showed through Hegel) and what might disrupt this sense more than being thrown into isolation, having only virtual labor to wage against a virtual stream of commodities shown specifically due to past purchasing and ad-interaction behavior, building a contingency of future value on the internal fixed data set of the rotating drum of consumer codex. This occurs as the 24-hour day reaches the capacity of populations and the limits of full employment. Time value diminishes because human labor can no longer keep pace with the planned global growth of capital—but only when kept under the yoke of scarcity (as described by Sartre). The common position becomes that the Irish potato famine was not an aberrance, but a trial run for this biopolitical exemplar. Asynchronous labor becomes useful, where no shifts are ever changed but instead overlap or radiate, traditional operating hours fluctuate at will, and employment becomes possible or necessary at the portal of the mobile market device—if we were not so tightly bound to the temporal regime. “What even is time?” If we have lost time, we have lost a claim to the vector of value.

This is the core of asynchrony, the temporal-spatial mode of now. Asynchrony functions through the developed rational technocracy, arising accidentally from the human use of human networks as the end function of an administrative temporal algorithm. Asynchrony overcomes distance by the instantaneous, thereby erasing the power of distance. Asynchrony does not encompass all, but, actuated, it is all encompassing. It hides the character of its use under that use itself. It is the floating point of individual mediation wherein contingencies of modernity maintain a shield of Gaussian blur comprehensive to the individual. Pandemia broke the tension between spatial-temporal synchronization, the perversity of a less-than-optimal asynchronous mode, and the demonstrable cruelty of demanding synchronization in a society capable of something else. Asynchrony works as an affect, a condition, a technical infrastructure, a pathology, a result of consolidating interdependent systems of organization and transmission, a clock of a second order. It is the quality of asynchrony in the recent shift that sustains the entirety of this essay.

If I Muck Up it’s Only the World Watching

In pandemia, the project of asynchrony appeared complete. In mid-March 2020, I flew into JFK airport in New York City. I walked through the empty airport to baggage claim. Huge, wall-sized ads for this thing called Zoom confronted me. I had, to that point, never heard of Zoom. I would come to use this video conferencing software daily, a software that rapidly and inexplicably became the only choice in education and work applications. This kind of market adaptation is either too good to be true, forged from the coincidental backdrop of ironic cosmic misery, or coordinated such that the mechanisms in place behind advertising, technology, and global pandemics are somehow interrelated. A shorthand for this could be the asynchronous apparatus.

Gilles Châtalet, in To Live and think Like Pigs, his 1994 engagement with the theory of James Buchanan, describes the emergence of a “triple alliance,” that of politics, economics, and cybernetics, which becomes “capable of ‘self-organizing’ the explosive potentials of great human masses.” I would like to expand on this idea throughout the rest of this essay, specifically with close attention to the time at the center of that triumvirate. Through history (or since the church lost control of time) science operates in the background of politics and economics, even in the context of major world conflict, with the savants or scientists emerging consistently on the side of the victor, with an easy social relation to truth that endows an unprecedented political mobility. Anyone with a cursory understanding of Operation Paperclip should agree here. Time slides through the French Revolution, both World Wars, the Cold War, the War on Terror; each period marks a specific development—from the idea of personal determination arising from the French Revolution, to the telegraphic and radio broadcasts of longitudinal World War use, to the Cold War satellite race, to the drone bombing campaign of the War on Terror—and the construction of time-broadcasting infrastructures are identical to those of the expansion of empires casting out their nets. Currently, we sit in the age of asynchrony, a style of time that makes inscription so dense that time is not thought of at all—until the shock of pandemia revealed asynchrony through its very sudden vacancy, an absence of intensity.

Châtalet’s engages not president James Buchannan, but the mid-20th century political theorist who engages rational or public choice discourse with the likes of Gary Becker and Milton Friedman. Buchannan developed the darker side of game theory at the Rand Corporation, discarding altruism in human behavior. The self-interest of politicians and bureaucrats then dominates the decision-making process, and Buchannan finds this a positive fact, one from which repetitive corollaries can be calculated. Becker, Buchannan, and Friedman represent several facets of the midcentury neoliberal project. The name drawing more attention in the context of cybernetics is Rand. The neoliberal expansion (a stealth political project designed specifically for economic ends) corresponds directly to the development of cybernetics. “To make an institution out of an idea is the surest way to stop it,” cybernetic pioneer Norbert Wiener wrote in 1948. Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, in their 2015 prospectus Inventing the Future, sketch a compact-yet-comprehensive history of neoliberalism that illustrates the virus of individuated market-driven self-interest working through the state by way of think tanks, media, and other cascading networks in a long-term purview of social control—that is to say, the soft exercise of power through a multivalent broadcast web, the self-correcting tendency of systems making bedfellows of the cybernetic and neoliberal approaches, and disseminating as idea through institutions, rather than becoming one (in a party apparatus). Srnicek and Williams declare the paramount result for the neoliberals has been the construction and maintenance of markets, with an emphasis on the state, and actuated by exterior means.

The ends of cybernetics—refining systems of modified data sets, defined by an inside/outside equilibrium. Wiener, who wrote one of the first texts on the matter, saw all biological, physical, and human movement as concentrated around messages of some kind. He simply defined cybernetics as "control and communication in the animal and the machine.” Andrey Kolmogorov took this a step farther, defining cybernetics as "the study of systems of any nature which are capable of receiving, storing, and processing information so as to use it for control." In the context of this essay, systems of time are coordinations of social reproduction that, in the feedback of the organization resulting from the time system, allow the time system to intensify and refine, thereby coordinating a greater concentration of social reproduction, and so on. The feedback of the time system (the product of the temporal organization of social reproduction) feeds into the organizational capability of the time system. We can only know this in the cybernetic paradigm, in that we define not only understanding, but the understanding of understanding, what Heinz von Foerster called “second-order cybernetics.”

Asynchrony, in the individual, dislodges second-order understanding, consolidating the first order of an observed system as a given, making the observing system an isolated formation of experience by interdependent dislocation. By fully activating the synchronized core, the second-order floats as if disconnected—when in truth it may access so many nodes as-good-as instantaneously that it is always connected—the rhizomatic captured, functionally regulated through timestamp tracking. Herbert Brun defines cybernetics as "the ability to cure all temporary truth of eternal triteness;" The project of asynchrony fits perfectly within that temporal vision. But pull back from a positive approach to the “California ideology” in engagements with cybernetics and a pull toward the subcultural. It is there—cybernetics—first disengaging from the music of salesmanship, to understand the underlying systems of organization or domination in which we willingly participate: “cyber” as the Greek prefix for control or govern (with another longitudinal aspect in the etymology of steering a ship, the Platonic ideal fixed to time) and time as a cybernetic system within a centuries-long and ever-tightening feedback loop. Ponder Stewart Brand, one of the ideological wanderers coming out of the ‘60s counterculture, a cybernetic advocate and a commune idealist, fervently supporting a project called The Clock of the Long Now This clock wound to 10,000 years sits inside a mountain on the territory of Jeff Bezos. Fading eschatology built into the hubris of asymptotic machine power enacts the assertion of the endless self. The development of information technologies has been explicitly tied to time and human control, especially in the psychic realm; the gesture of the 10,000-year clock implies a consciousness of precarity, a fear of evacuation or abandonment, the continuous insistence of time systems as representative for the zombie extension of a system failing more often for all but the elite—or this is simply the design of the clockwork.

When McKenzie Wark declaims in 2019 that “capital is dead,” the ownership of the means of production transmuting to the means of organizing the means of production, discerning a sense of complete synchronization—meshes and networks overlaying one another in intense coordination, ensuring flows of goods and capital remain fluid, out of control in the sense they need no control, synchronized to a degree of the apparently automatic, the consolidation of the first-order observed system. I see Wark’s melodramatic book, Capital is Dead cited often; the climate-futurist-hyperstitionist Holly-Jean Buck borrows language from it, and Jody Dean’s 2020 piece on neofeudalism begins with a question posed by Wark (“is this not capitalism but something worse?”). But Châtalet had already written in 1994, “capital is no longer a factor of production, it is production that is a mere factor of capital,” making a comparable point as Wark’s in a more constructed folio. What we take: that the exploitation of labor, financialization, and global infrastructures interlock to the point that value is constantly produced in the efficiency of a self-organizing feedback loop, to the effect that these mass amalgams require a new set of second-order capital handmaidens, the derivative function of neoliberalism overtaking actual material, as Brian Massumi writes in 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value. Wark, at the least, provides a useful shorthand for the echelon of global capital, namely the “vectoralist” class, the ultra-billionaires of the extraterrestrial century who coordinate the networks which coordinate. I see the vectoralist as the steward of asynchrony. The vectoralist tugs the cybernetic capillary of feedback response that runs on the same infrastructures from which other transmissions were constructed (always networks of time transmission) and upon which more will be relegated.

The ownership and privatization of time no longer comes into question—on both long- and short-term levels. Many forks in the road of social progress meander back toward the ruts, deceptive routes to reproducing aesthetic and economic conditions without substantial systemic change, a turmoil of predictability that Giorgio Agamben recently identified as “stasis,” the perpetual movement between the private and the public, a coordinated tension of the biunivocal. The increasing frequency of historical-level events, and the rapidity of course correction away from possible new futures (including that of Trump, the failure of a coup, protected from without by The Corporation) make this subtly apparent, and what once seemed a mainstay of postmodern theory becomes a mainstream statement of ever-common observation: we, as subjects tied to the static fiction of the synchronized, stick in time, dislocated from the limits of the clock, in interleaved networks of telegraph and telephone, the airwave modulation of radio and television, the pulses of fiber optic cables, cellular networks, and satellite beams. The newest development of communications technologies allow developing nations to leapfrog over industrialization and into the world computer-knowledge economy. All the while, data compression achieves new tiers of clarity and economy, as Moore’s Law—an empirical postulate originating around 1970 that the presence of transistors in a dense circuit (i.e. computing power) doubles every two years—oscillates in harmonics. And this is the level of “inward growth,” the attempted interior extension of eternity. For example, in 1967, we moved from reductions of “the day” as the standard of time measurement, to 9,192,631,770 oscillations of the cesium atom in its ground state, in this precision coincidental duration to what we’d already determined by centuries of rationalization to be the second. “What even is time?” In this case, a number of a microscopic immensity, the frontier to the right of the decimal.

When time expresses urgency as its dominant characteristic—an overlaying rapidity of simultaneously constant, segmented, and multivalent transmission—even in a pandemia of forced immobility, it is not the virus itself that corresponds to affect, but the viral. Through Lukacs we might abstract why one might decline to wear a protective mask in pandemia: an unwillingness to come to terms with the category of totality itself. Žižek, in one of two 2020 books on the pandemic, subverted Hegel and told us not that spirit is a bone, but that spirit is a virus. How could one argue with unmasked intolerance? Vaccination blocks the path of history! Bad science allies with the wrong side of history! Kamala Harris stood on the debate stage with Mike Pence and declared she would not take a vaccine developed under the command of Trump. The current of asynchrony demands complicity of the individual, an imposition of universalism, false or not, of the most particular kind, to the consensus negotiation of politics and science. In a refusal of that, the horizon of belief turns inward—as the scalar of time moves inward—unable to coordinate with the reliability of the Other, by negating Reason, or, somewhat disastrously, constructing a false and unfounded Reason—the lack of proof being the proof— in the narrative construction of the asynchronous apparatus. The asynchronous subject fails to negotiate good faith amid accelerations of life-threatening proximity—Pascal’s wager but for a liberal democracy on the brink of collapse. Pandemia forces this bifurcated thinking to not only the possible, but to the Real, by immobilizing entire populations, applying the biopower of nation states to the representation of efficacy on a world map, and implementing biometric tracking to the individual. Even the most blinkered are forced to contemplate (this is not to say accept or embrace) the intricacies of a world system and the global flows of commerce and communication in which they are but a data mote, and in fact little more than a vector for disease. This represents the asynchronous cognitive map: an impossible attempt to situate oneself amidst the synchronized core, precisely because it is not within this core, but without, a transcendence of the concrete aspect of time-space relationship to a disoriented abstract, a position that holds possibility at arm’s length through the alliance of the technocratic arts.

It Would Be A Dream That Had Never Been, That Would Come True

As a result of its comprehensive machinery, asynchronous temporality itself in the recent past moved into the static realm, where the public time of commerce and the private time of leisure merged to full solution, beyond working hours never ending, where leisure activities generate value in their various strands of feedback, as Neta Alexander described in the context of David Harvey’s A Brief History of Neoliberalism. There, at the cybernetic streaming service, an often-repeated observation of the globalized, “late capitalist” world is the apparent endless present, where culture, upstream from politics, folds back onto itself—both due to and despite increasingly segmented and fractured experience, dissected by ever-more precise instruments—where time does not pass, but simply “is,” infinitely dense in its inscriptions. Governed by a cybernetic warden, human archetypes of postmodernity become little more than “thermostats” of input-output signals making fluid the “market democracy” of tertiary industrialization, the move from producing value in the factory to value on the screen. The turbo power of communications networks aggravated the isolation of pandemia, the endless screens and screening and screens within that screening—the nightly news blaring from the flat screen in the vaccination site—the asynchronous totality, the reality of the new condition of pandemia, being certain of so much, with a knowing complicity in the system of domination and exploitation (a second-order understanding of the violence of synchronization) and without a way to disengage (asynchrony) if only for the social responsibility of isolation. This is the intensity of the “now,” the deception of the endless instantaneity that we have indeed met with some kind of political and cultural singularity. To be sure, it is false! It is a coordination of time-space and information systems that exceeds the limits of physicality by inward growth and vectoralized calculations, so dense its absence shocks more than the audacity of its presence, as pandemia revealed.

This position of timelessness in advanced/late capitalism, first theorized by Fredric Jameson and Jacques Derrida as a cultural phenomenon, atomized into daily life, in the decades since, from the macro to the micro, into a technical and psychic phenomenon: asynchrony. In music, the proliferation of “the loop” represents a certain dislocation from forward movement in time, remarked on often in the anthology The Politics of Post-9/11 Music and elsewhere at length by Mark Fisher. This reflects “[...] the dominant mode of being of external reality [as] time itself,” as Jameson presciently wrote in 1971, at the nascence of the neoliberal consensus. Time freezes like a river—the surface can be grasped in representative solidity, while the flow remains out of touch. The very system of measurement sits outside the argument by fiat, a hyper-Newtonian constructed psychic absolute. This disconnect between the awareness of time passing and its incommensurate experience reflects the state of the asynchronous subject. The individual—like two students in one room constructing different memories—generates a monadic vision through the mobile market device, incompatible with totality and contradicting all others, while simultaneously overlapping with all others—yet because of the multivalence of the experience, no two Venn diagrams, in the endless universe of overlap, are the same. A contradiction, to be sure, and one arising from the ubiquity of information and entertainment that the individual constantly may reify the conditions of existence. The triple alliance ensures flows of economy, including—as David Harvey described in The Condition of Postmodernity (1989)—economies of image. We now face more coordinated iterations of Debord’s “integrated spectacle,” both diffuse and concentrated, emanating from power centers but lacking permanence in social cohesion, isolating and thereby unifying by the very isolation of the atomized mass. In pandemia, cultural institutions closed—cinemas and the like had already been on the brink, as a consequence of on-demand/asynchronous entertainment technology. There, the asynchronous subject nullifies the “boring” as a narrative category, even in staying home for days on end, fearful of death, the invisible death of Covid-19; the demand for affirmation of life becomes immediate, constant, and asynchronized. Formally within the asynchronous, always available are spectacles in durations either monolithic or miniscule. The former arrives in the phenomenon of the “binge watch,” a practice of durational masochism and an affect of uselessness, the cultural expression of mechanical malaise, the second-order observation of a system observed—the quarantine of pandemia enabled a never-ending binge watch. Here, the viewer watches episode after episode of a television serial and entire “seasons” exhaust in a matter of hours. The viewer may “skip intro.” Content needs no introduction.

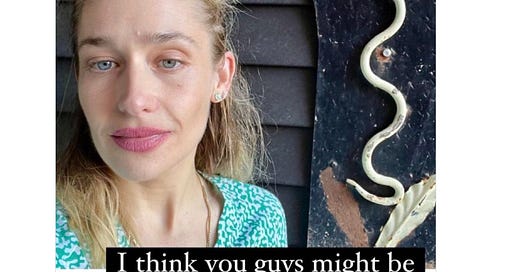

In one episode of a reality show called Wife Swap the one family was devoutly Christian and the other actively Atheist. The father figure of the Christian family described with relish his practice of soaping a child’s mouth over and over, “until he [the child] cared.” The Atheist family sported a husband figure known in a niche internet micro community, where he spends 18 hours a day broadcasting an Atheist internet talk show. One son in that family does chores all day and his younger brother is sent to a daycare, so that the wife figure could have all day to manage a second, digital family in the video game The Sims. How does a family function in the production of the virtual? The thing to look at is the position of labor and the production of morality by the contrast of the edit, the absence of unified time in the godless home. In a different but similar episode opposing the pastoral and the secular, a super-structured family swaps matriarchs with a more deconstructed family. The deconstruction wife, upon seeing how regimented her host family lives, throws their “brain” in the fireplace. Their weekly planner smoldering in the hearth, the 15-year-old son, pious and kind, erupts in anger. He yells, “How are we supposed to know if family came over for Christmas?” One faction sees the calendar as crucial personal history, the other as a potentially repressive grid of social organization. Gender norms for whatever inscribed meaning are queered, here, in Wife Swap by a simple side-by-side of time. The performance of gender is put on blast by the sheer contrast of an opposition—not a full negative, but any opposition at all. By filling this absence that it creates for itself, Wife Swap functions as critique. In yet another episode, a Mennonite family swaps wives with a family of punk rockers who operate a bar and small music club out of their home. During the filming of the episode, the father figure loses his job as an office administrator, relaying to cameras that his superiors did not find it appropriate he aspired to the rock star life. Had this been filmed within the paradigm of asynchrony (this particular episode was produced before 2005, the advent of the mobile market device) it is possible the punk father may have distanced himself by gig work from both an authority of lifestyle and the aesthetic judgment of the subculture in which he aspired. The personal becomes irrelevant to the production of value. Skip intro skip everything. In media res replicates in social conduct. Why then does the media report that, under pandemia, workers who dropped their commute in order to work from home ended up working more hours? Skip the intro of commute, the environment completely virtual, to labor in the enterprise of intellectual property, a demonstration of the asynchronous position of labor and the irrelevance of what Debord called pseudo-cyclical time. In the virtual environment, communal affirmations of the self, an ordering of one’s place in the world, dislocate to neurochemical feedback loops of social media dopamine production. Economy and cybernetics ally easily, here, building an instant affirmation into value production. This personal archive of the post ritual exists ostensibly for virtual others, rendering the subject virtual, holding the position of privilege. To Lacan, the true purpose of the masochist is not to provide jouissance in the other, but to provide its anxiety—the asynchronous. In the digitally constructed, voluntarily virtual, the self is an individually affirmative hall of mirrors, a Narcissus without an Echo. The constantly mediated must not distinguish hyperreality from experience (I’m reminded of the intelligence gatherers in Neil Stephenson’s book Snow Crash) and the construction of the subject becomes completely virtual, foreshortening time, triviality, the “boring” narrative of life itself. The declaration, “I saw that on Facebook already” brings conversation to a halt. Skip intro skip everything. When all is “post,” that is to say after, past, already happened, intro-to-be-skipped, the present exists previously (and tomorrow is already algorithmically accounted for) purely as a mechanism of reflexivity, the anxious affirmation machine. Yet the celebrity theater of the biunivocal political spawns enough interpretative surplus value to make an opinion generator out of the most discontinuous subjects. The already ruthless efficiency of consensus politics accelerates by way of allowing extremism to appear, only in order to distract from the inaction of the center. That’s the purpose of the Dwight character on the US television series The Office, the exquisite form of binge-watch, a show about a dying paper company—that is to say an asynchronous gestalt guidebook to ascending labor to the virtual. Dwight’s amodern/fundamentalist prosthetic (revised past-future perfect survivalist) is made to look absurd, against the hauntology of Pam’ and Jim’s Protestant Oedipal ethic. “Good Mommy, Good Daddy/Bad Mommy, Bad Daddy.” Taken further, off the screen and onto the other screen, when it comes to online dating, algorithmic matching masks a technological form of arranged marriage, dislocating the importance of cultural/social reproduction to the technocratic success of copulation, a thoroughly dishonest arrangement that postures individuality against the cold logic of machines. The success of matchmaking television like The Bachelor or Married at First Sight rationalizes what was once fully Othered, through the Western language of the Oedipal image commodity. In the malaise of pandemia, we binge-watch Sophocles, a Sophocles so on-the-nose it feels fake. The asynchronous apparatus incorporates the first-order function into its own second-order critique. The often-ambiguous Love on The Spectrum holds the position as a future-leaning attitude toward sexuality and psychology; this program follows adults with autism on their quest to find life partners. The titles of the sections here are quotes from the earnest and ultra-logical subjects of that program.

We’ll Find As We Go I Suppose

As I write this, we gaze into an ocean of fire, microplastics move into food supplies and appear in the bodies of newborns while outnumbering stars in the Milky Way, inequality gaps widen to the abyssal, floods sweep lands in a biblical prelude, and so on and so forth, all the anxiety inducing news that’s fit to arrive on the same devices through which we conduct our labor, leisure, and love. A reassessment of spatial-temporal mode presents an opportunity to reclaim productive, meaningful, and human endeavor beyond sustainability in a world more fraught with precarity than ever, and somehow simultaneously measured as more prosperous than ever—yet only by ratio, the inverted pyramid a colossus of chit. It would be disingenuous to hide in darkness the tremendous hope of a strategy that reconciles this gulf between dispossession of a foreclosed future and a prosperity that spans humanity. Already I run the risk of banality: world peace is the answer of the pageant winner, the universally appropriate abstraction to the question of, “why?” Yet it must be articulated: there are vastly different versions of peace. Fascism offers its own—the boot on the neck of the Other, the obligation to a fixed ideal (the devotion to the Oedipal). Would it then invert tyranny to suggest disengaging from the dominant thought of the last few thousand years? If this implies a new balance, it must be theorized from a new source, beyond liberal democracy as we know it, where “value” diminishes in the gravity of history and the escape from this endless present shifts to the consciousness of a before and thereafter, the history after the end of history. These phrases such as the “end of history” indicate a blunt kind of indebtedness, that of political jingoism nonetheless deeply influential to shaping the world from which these thoughts arose. Fukuyama, in particular, shoulders the blame for the spread of a blasé attitude toward the destructive pace of liberal globalization in the 1990s and exploding after the neoconservative rationale provided by September 11; even if Fukuyama’s essay is misinterpreted commonly (Hegel had already made such a pronouncement a century earlier) the title alone provided the motto for an expanded American global hegemony. Is this the peace we wanted?

The endless war ends again, the Bad Infinity, and the 20th anniversary of the towers crumbling passes like salt into pixels. Marking a derogatory shorthand, hardline liberals, naked imperialists, and war crime apologists quipped on the “forever war” spawned from that tragedy. But it must be considered: the dictum, “never forget,” is itself a political slogan of time, and the ultimate instance of the postmodern revisionist project. The fact the establishment borrowed the phrase from the Nazi holocaust should demonstrate this, for the reason it has overshadowed the Nazi holocaust by shorthand. Position “never forget” against its inverse, “always remember.” In the secondary farce (after the first tragedy of fascism) “never forget” lacks the heart of “always.” The heart of “always” is love; the heart of “never” is indifference, assumes indifference. “Forget” is a warning; “remember” is the language of the fond. We are not meant to remember. We are meant to never forget, the insistence of that affect; we do not forget empire, a formation of imperialism that we can never forget, lest we become subject to history, and halt an economy of speculation relying on movement around a nexus so complex it appears unknowable, unrepresentable, to know the opposite of what should be known: powering down the imperial engine. That serves the exact opposite function of never forget—it is the phantasmagoric othering of then, the impassable present, rather than the apprehension of the impossible: always, eternity, beyond sustainability. We are not meant to remember, because we are meant to transverse the rupture of that moment as if it never happened, an attempt to freeze the meaning there and continue on the toric path at the end of history, the biunivocal tradeoff that extends endlessly the temporal regime of communicative capitalism. The dialectic between pandemia and a post-Afghanistan America radicalizes a new horseshoe contingent, moving by interior failure to exterior consciousness. The lie of American omnipotence eventually fell, while the war of infinitude (we’d traded cowboy hats for assault helmets) stretched back into the homeland by an incomplete sense of concept—the broken conclusion to the founding mythology of the frontier. Who are we without a war? The new threat is within, as white Christian sectarians begin militating in a way not unlike the balkanization of Islam following the American ventures for oil in Central and West Asia. By some legitimate reports, there are currently double the threats of domestic terrorism in the US against international variants. In a recent interview, Noam Chomsky made this remark:

Suppose that on 9/11 the planes had bombed the White House. Suppose they’d killed the president, established a military dictatorship, quickly killed thousands, tortured tens of thousands more, set up a major international terror center that was carrying out assassinations, overthrowing governments all over the place, installing other dictatorships, and drove the country into one of the worst depressions in its history. Suppose that had happened. It did happen, on the first 9/11 in Chile in 1973, except America was responsible for it, so no one even knows about it.

What he refers to is the coup in which US intelligence services helped overthrow democratically elected Salvador Allende and install the junta of Augusto Pinochet. The latter, a brutal dictator of untold horrors, sits high in David Harvey’s neoliberal pantheon (along with Reagan, Thatcher, and Deng Xiaoping). Chile in the ‘70s became the testing ground for the theory of “The Chicago Boys,” the monetarism of Milton Friedman, and the disruption for the explicitly cybernetic socialism designed by Stafford Beer and Project CyberSyn; I think the span between the two 9/11 operations can be seen as the era of unchecked neoliberal expansion. The era after 2001 seems to be the beginning of the end of American hegemony, even in the economic standard indicators of human rights indexes (freedom of the press, inequality, instability, and so on). While I am positioned in what follows to comment on the US as the focal point of these remarks, it comes to terms with a counter-hegemony, against a failed emancipatory project.

III. THE PRODUCTION OF ASYNCHRONY

Physics, today, no longer denies time. It recognizes the irreversible time of evolutions toward equilibrium, the rhythmic time of structures whose pulse is nourished by the world they are a part of, the bifurcating time of evolutions generated by instability and amplification of fluctuations, and even microscopic time, which manifests the indetermination of microscopic evolutions.

– Isabelle Stengers, 1997

From the intellect, biology and physics bind into rotation in the earth, of day and night, of seasons (though seasons are themselves contingent on climate stability and therefore not absolute to region or temporal stasis). Yet these motions of bodies are dividends of the aggregate of a universal motion that, until fully indexed–an untenable possibility at present–the project of “time” can never be complete. Terrestrial time is rote, basic, and leveled by the observable. Social constructions of time have ancient commonalities, even if coincidental, including the development of weeks of different lengths, the coordination of lunar cycles, and religious festivals—psychic consolidations of repetitive corollaries. You’ll understand me, then, to distinguish the extensive future of measurement from the durational eternity. As Bossuet said: “By means of the time that passes we enter into the eternity that does not pass.” A fine line or no line at all separates what we may never imagine, and what we may never know. It is that very imagination to which I appeal—the wager is not the impossible, but the impassable present. A high-stakes and urgent present populates the consciousness. The future arrives by means structurally suspect, yet appearing logically sound—or worse, rational! Though he slept through it, Gregor Samsa’s alarm clock made “an ear-splitting noise” that morning. Better still, take “The Warden of the Tomb,” who never sleeps in order to guard a centuries-old body, 60 years of dreamless sentry; he has worked himself not to death, but to whatever the opposite of living is. This projection of coordinated life calculates averaging functions, the micro divisions reconciled to a unilocular stasis, the condition of asynchrony.

We explore the relationship between time and power—the structural development of precision predictability. All time systems account for a future. The planning of agriculture, in the first instance, presents a self-evident temporal forecast of social reproduction. In anthropological study, the markings of notches on excavated wooden rods have been interpreted to be coordinating the week, they tell us, tracking sunsets for the meeting of a marketplace. These are the determinants of algorithms that foretell the mediating presence between at minimum two nodes, for the purpose of reproducing social conditions. It is the same wager of an alarm clock in modernity, the supposed agreement between expanding populations on a fixed frequency of simultaneity, the wager that when I leave for the office so, too, will you. Every clock on earth directs a momentum of social life (an attempted containment of the élan vital) through a temporal organization that synthesizes the determinate future. As populations and territories expand, it falls upon power to consolidate simultaneity. It should be an obvious thread to pull, as these systems of organization are fundamentally linked to some external indicator and therefore some kind of common sense. “The opening lines of Hesiod's ‘Days,’” Harold Innis wrote, “mark out the two chief moments of the farmer's calendar, ploughing and sowing, by the rising and setting of the Pleiades; and that faintly glittering constellation has been a farmer's guide through many centuries.” Yet we construct this common sense, in the case the problem of simultaneity relating to a certain constellate perspective; what we find in this “natural world,” the boundary of which we also construct, is interpreted in ways that become convenient to advancing certain practices of governing, inscribing the subject with a rhythm of governmentality. These rhythms through history become increasingly dense until the opacity of synchronization reaches a point that makes time useful in new ways. It is at that point of opaque synchronization that asynchrony appears as an instrument dislocated from the produced continuity of time, by appearing above and around the fully solidified temporal core.

In a 1915 essay by J. T. Shotwell “The Discovery of Time,” the author distinguishes between the calendar and chronology. The first is the mathematical calculation of repetitive corollaries; the second is the study of time itself, which cannot be measured, but is made in the instant of the everyday, flowing constantly from the flux of human activity. The calendar made chronology possible, as the rhythms of the market (for why the week was first coordinated) the ebb and flow of agriculture, one that recasts the book of Genesis as attributing to the feminine the synthesis of predictability (for why months and solstices are calculated) and the seasonal patterns of hibernation (for how the future is negotiated) allowed the derivation of record keeping. Shotwell argues these are the basis of scientific history and to a massive civilizational extent. The sun provided the framework for the calendar. In other words, the origins of the calendar precede the origins of chronology. The origins of the calendar, says Shotwell, are from when man settled in the soil and began to farm it. He claims time and space are joined and the first to accept this was they who cultivated earth. This assumes futurity, as does the hunter who negotiates feted prey. The discovery of time shifts epistemology toward a self-conscious imagination and memory, the building of pattern recognition and correlative function of future anticipation, an internal synthesis of exterior stimuli, a computation of messaging. We make time from reconstructing the past—not that we know the past; we know things in the past happened at frequencies of predictability, within the limits of our perception. Shotwell concludes that the Greek and Roman rivalry, in the disagreements about beliefs of the moon, could be reconciled in their consistency in their belief in the stars. At that point, the maintenance of continuity becomes less tied to agriculture and more to the scaffold of empire.