Sarah Chekfa (IG)

(Substack)“To discover truth, it is necessary to work within the metaphors of our own time, which are for the most part technological.” —Meghan O'Gieblyn

“In God we trust. All others must bring data.” —W. Edwards Deming

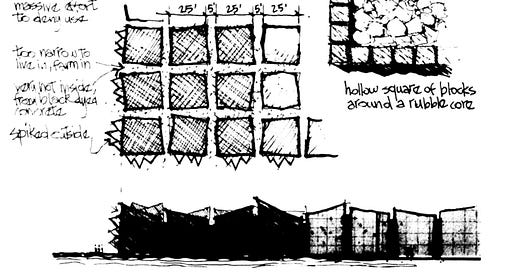

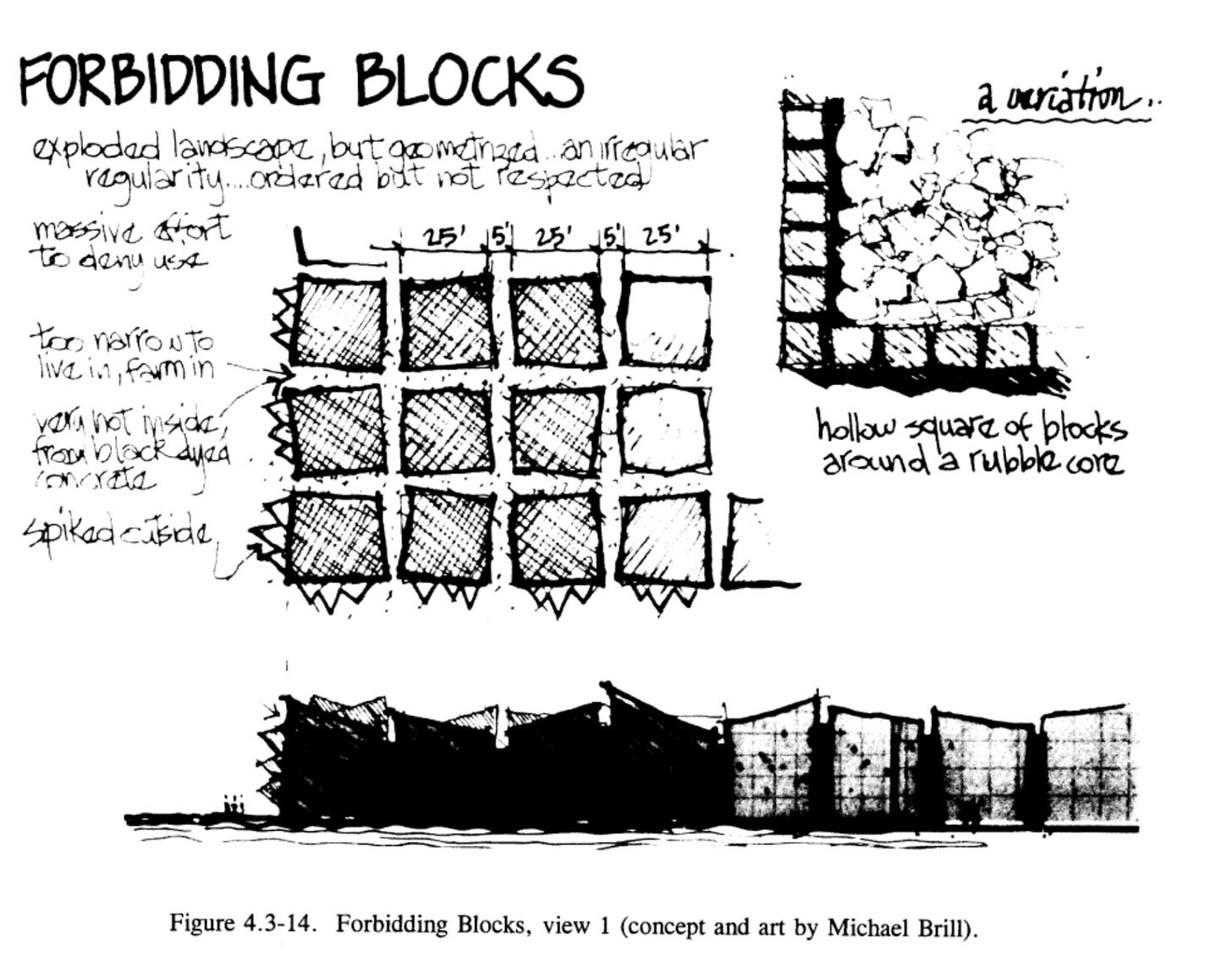

“Stone from the outer rim of an enormous square is dynamited and then cast into large concrete/stone blocks, dyed black, and each about 25 feet on a side...The cubic blocks are set in a grid...You can get “in” it, but the streets lead nowhere, and they are too narrow to live in, farm in, or even meet in. It is a massive effort to deny use. At certain seasons it is very, very hot inside because of the black masonry’s absorption of the desert’s high sun-heat load. It is an ordered place, but crude in form, forbidding, and uncomfortable.”

Such is the concept known as “Forbidding Blocks,” a physical marker speculatively designed to signify that a land is “shunned..poisoned, destroyed, [and] unusable” to preclude human intrusion at nuclear waste repositories within or above the order of magnitude of 10,000 years into the future. It is one of the designs explored in a 1993 report from Sandia National Laboratories for the US Department of Energy for the Waste Isolation Power Plant, an extensive foray into the field of nuclear semiotics that aimed to develop effective and prohibitive warnings for future generations who could not be presumed to speak our languages nor understand our symbols.

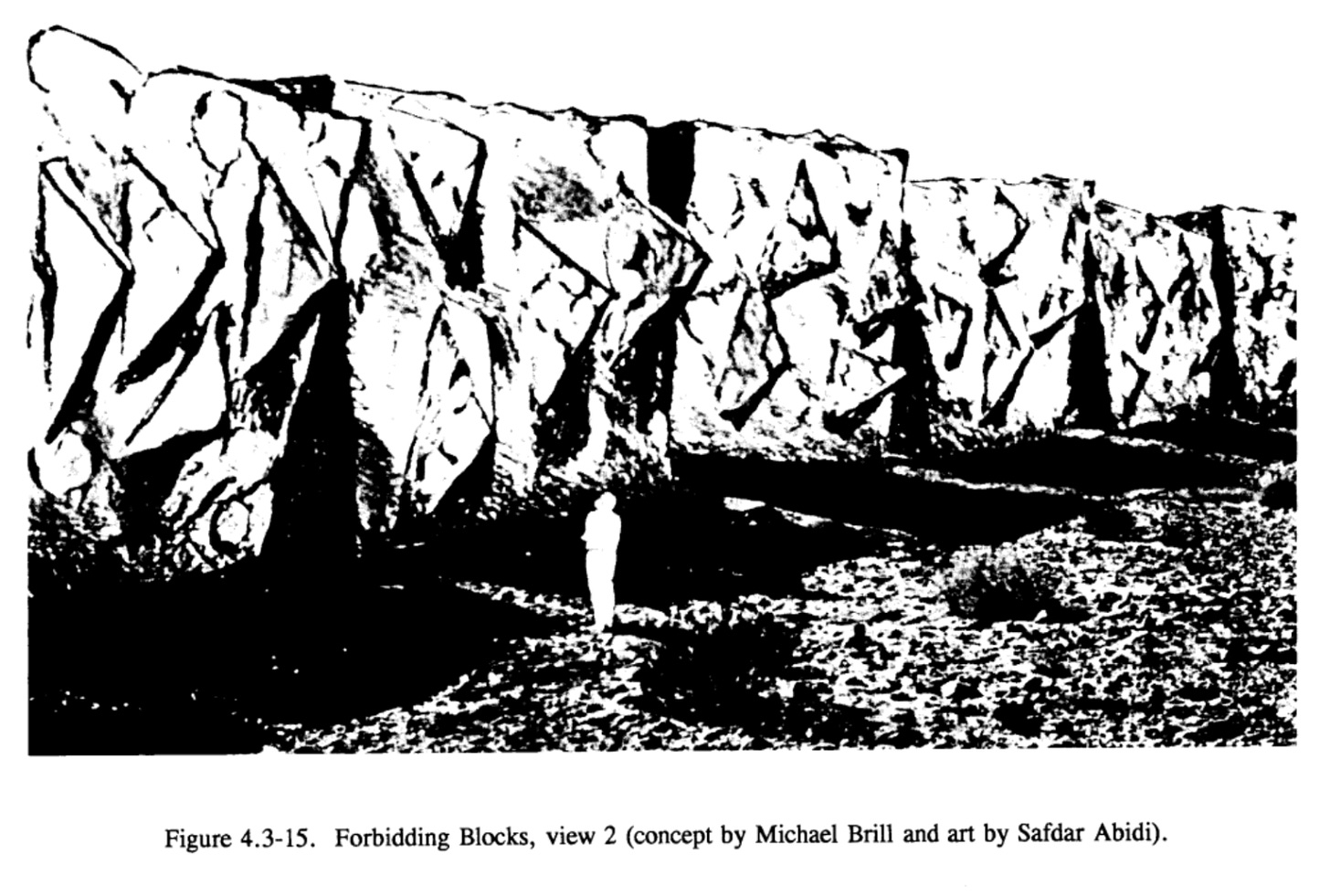

While the concept was never developed, an unintentional iteration of it persists in the present day: “Forbidding Blocks” is a phrase that comes to mind when confronted with images of contemporary data centers. Yet rather than performing the role of earthly deterrent, they “house...[sic]” IT infrastructure for building, running, and delivering applications and services, and for storing and managing the data associated with those applications and services (IBM).

The language used colloquially to refer to our age of compulsory connection is often heavy with binary. Online, offline. Digital world, physical world. Yet this binary is a false one—as is that of Heaven and Hell, some techno-utopians might retort—conveniently shrouding the inherent physicality of the “digital world,” which is borne of this earth, and is inextricable from it. All our data—rapaciously accumulating with every innocuous act, from texting to online shopping to Tweeting to downloading PDFs to watching porn—the list undulates into infinity—has to live somewhere. That is: in data centers. A data center, then, is the physical space containing the machinic paraphernalia—servers and storage systems and cables and such—that the virtualization of “the Cloud” necessitates.

"Data centers power modern life and yet they're rarely considered as pieces of architecture," says Claire Dowdy, who curated an exhibition on the design of data centers at Roca London Gallery last year. "But as they mushroom across the globe, it’s time we thought of data centers as a peculiar, and peculiarly challenging, new building typology...We are producing an architecture that is not constructed, or located, relative to human scale, but instead is a physical manifestation born out of, and subject to, global flows of information.”

This unrelenting deluge is recognized in everyday parlance as “big data.” “To become part of depth of infinity, such is the destiny of man that finds its image in the destiny of water,” writes philosopher Gaston Bachelard. A sense of infinity, an everlastingness—this is what divinity promises. And so it is not unsurprising that data that has grafted itself into the valley of the gods, historian Yuval Noah Harari warns: “Just as divine authority was legitimized by religious mythologies...high-tech gurus and Silicon Valley prophets are creating a new universal narrative that legitimizes the authority of algorithms and Big Data. This novel creed may be called ‘Dataism.’” In his book, Homo Deus, Harari suggests that dataism “declares that the universe consists of data flows, and the value of any phenomenon or entity is determined by its contribution to data processing.”

Some observe that big data is mythological in its gravitas. As Roland Barthes suggests, the role of myth is to consecrate beliefs that are contingent, rendering them beyond question or criticism (Farida Vis, 2013). Myth, then, becomes a mode of communal reinforcement, a social phenomenon in which, upon consistent attestation within a community, regardless of whether sufficient empirical evidence affirms it, becomes regarded as fact.

Such is the mentality by which many regard big data, believing that these vast data sets provide our society with greater intelligence and knowledge that can produce previously unthinkable insights “with the aura of truth, objectivity, and accuracy” (Boyd and Crawford 2012). Aura, according to Walter Benjamin in his 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” is that quality of an artwork that is fundamental to it and unreplicable through mechanical reproduction techniques. To regard the potentiality of the results that data offers us as infungible assigns her a competitive advantage, renders her a unicorn—that mythological creature that has contradictorily been associated with purity, seduction, and divinity throughout history (JSTOR, 2021). In fact, data scientists themselves are often referred to as “unicorns” (Victor S.Y. Lo, 2019). And data is often alluded to as pure (“data scientists require computer science and pure science skills beyond those of a typical business analyst or data analyst,” reads an IBM piece of “thought leadership”), seductive (“How to make data look sexy,” reads a CNN headline from 2011), and divine (“All the eternal questions have become engineering problems,” writes Meghan O'Gieblyn in her book God, Human, Animal, Machine.)

So data is our religion. But what is religion without the architecture of monument? Religious monuments signify “historical moments...worthy of commemoration” (Phillips, 2020). Stonehenge, the Ka’bah, the Tian Tan Buddha...and now, belatedly joining their ranks: the data center. Experimental architecture is understood to denote that creative branch of architecture that aims to unsettle established architectural conventions, designing radically new architectural configurations and structures yet unimagined and unseen (Melbourne School of Design, 2018). Yet it is important to recognize that the adjective “experimental” is polysemous. “Experimental” can signify that a new invention is “based on untested ideas or techniques and not yet established or finalized (i.e., an experimental drug).” “Experimental” can also signify—now, archaically—that an idea is “based on experience as opposed to authority or conjecture (i.e., an experimental knowledge of God).” Data centers, then, can be seen as the poster child of this revisionist theorization of experimental architecture: big data is indeterminable, bound to what computer scientist and physicist Stephen Wolfram calls “computational irreducibility,” whereby the only way to ascertain the future state of a system is to let it transpire (Jag Bhalla, 2021).

And so it transpires. Donna Haraway, in her 1988 essay “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” coined the term “the god trick,” observing the way that “universal truths” seem to be engendered by “disembodied scientists” who observe “everything from nowhere” (Miranda Marcus, 2020). Now, data does not even have to be consciously collected by a human being—machines take care of it all. And so the scientist is displaced by data: data is always collecting, receiving, processing. It is an omniscient God, and the data center is both its medium and its monument.

The optics of the data center are not unlike those of a cemetery—rows and rows of those “Forbidding Blocks,” not dissimilar to black boxes, comprise its internal organs, stacked up and blocked off in an orderly gridlike pattern for as far as the eye can see. The effect is bewitching, and the halls begin to feel holy, perhaps because this machinist symmetry accords with a belief that has been around since antiquity—that a divine power conceived of the universe according to a geometric plan. Plutarch attributes the notion to Plato, writing that "Plato said god geometrizes continually.” Two of the messages that the aforementioned Sandia report intended to communicate through design affordances to future visitors to a nuclear waste site capture the aura of the data center—that is, that of an anti-monument: “This place is not a place of honor... no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here... nothing valued is here...What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us. This message is a warning about danger.” Such is the way data centers are perceived: “Banal,” “creepy,” and “ominous,” they are diagnosed by a Daily Dot article. Google prefers to call them the “heart of the internet.” Though perhaps they recognize their lack of aestheticism, because in 2016 the company launched the Data Center Mural Project, paying artists to “reimagine...[their] facades...to bring a bit of the magic from the inside of [the] data centers to the outside.”

Karl Marx conceptualized the “apparently magical” nature of the commodity to be fetishistic, a notion in anthropology that refers to “the primitive belief that godly powers can inhere in inanimate things” (Dino Felluga, 2002). “A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.” So data can be understood as a commodity, and thus as an object of fetish that contorts reality in its own image. What is real is whatever it portends, and whatever it does not portend is not real (Jag Bhalla, 2021).

And just as the aforementioned Forbidden Blocks emanate immense amounts of heat, so too does the data center. But its heat is not the doing of the sun—rather, it is a side effect of the vast amounts of energy required to store and process the data. Temperatures can rise above 95°F. Perhaps this is dataism realizing its rendition of Abrahamic Hell.

One technology firm recommends that the ideal location for a data center is a single-story, detached building with no other functions (other than IT and tech support). The singularity of the data center is reminiscent of the singularity of a monotheistic god: nothing can compare, or even come close to it physically—it is all-powerful, all-encompassing, and ultimately alone in its grandeur.

Religious monuments “represent sacrifices and suffering that many religious people had to endure in order to practice their faith” (Adrienne Phillips, 2020). And how we sacrifice and suffer for our data. As the latest issue of Paradigm Trilogy: Man vs. Machine opines, “It’s your civic duty to accrue data. Every move you make is money in the bank of someone else. Platforms seduce their users into performing unpaid work—uploading the texts, photographs, videos, and music that are the raw material of the digital world—while mining their metadata to create new markets for corporate and military surveillance” (Paradigm Trilogy, 2023). In her essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” Ursula Le Guin suggests that the earliest human tool was not the spear, but the vessel. And so it is that humanity has come full circle, conflating the two contenders: the latest human tool to “disrupt” our way of life is the data center, which at its core is itself a carrier—of our data—that simultaneously is capable of harm, as a spear. “Don’t Get Comfortable,” warns AKCP, the world’s oldest supplier of network-enabled sensors, in a blog post detailing safety and health recommendations for data center employees. “A false sense of security could be the biggest threat for human employees in a data center.” It seems like good advice for all of us.

Data centers emanate a noise pollution that is unregulated by the government: the tremors of hard disks, the reverberations of air chillers, the winding of diesel generators, and the revolutions of fans harmonize in a haunted white noise, a disconcerting hum that not only irritates but actively harms the communities in which they are situated. One software engineer was diagnosed with hypertension, and now meets recurrently with a clinical therapist to manage anxiety exacerbated by the data center’s buzz (Steven Gonzalez Monserrate, 2022).

What an ecologically decadent life we allow our data to lead! The Cloud now possesses a carbon footprint larger than that of the airline industry—at 200 terawatt hours annually, data centers holistically squander more energy than some nation-states, even. A single data center can use enough electricity to power 50,000 homes, annually allotting 2% of global carbon emissions. And the increasing amount of data that is collected—2.5 quintillion bytes daily—leaves the cloud no choice but to swell, leading to the construction of more data centers across the Earth.

And soon, perhaps, our cloud will hover over the moon. In March of 2023, cloud computing startup Lonestar Data Holdings raised $5 million in seed funding to establish lunar data centers. “Data is the greatest currency created by the human race,” Chris Stott, founder of Lonestar, proclaimed in an April 2022 statement. “We are dependent upon it for nearly everything we do and it is too important to us as a species to store in Earth’s ever more fragile biosphere. Earth’s largest satellite, our Moon, represents the ideal place to safely store our future.”

The proposition is not without its poetic undertones. Data centers consume vast amounts of water, the same element that destroys the electronics that connect to, and presuppose them. It is under the seas where the fiber-optic cables that make data transfer—i.e. the Internet—possible are situated (Dan Swinhoe, 2021). And it is the moon’s gravitational pull that generates the force that causes the tides of the sea to ebb and flow (NASA, 2021). To situate data centers on the moon would, in a twisted way, bring the cycle to full circle, a grotesque adaptation of the early Hindu belief that the souls of the dead returned to the moon to await rebirth. Yet data centers will unavoidably provoke space pollution, surfacing “a settler-colonial futurity that eliminates other types of possible futures and relations with the environment...dealing with the myriad of possible pollution legacies rather than refusing them in the first place” (Yung Au, 2022).

Yet making like iconoclasts and razing the very notion of the data center from the planet is too drastic, too utopian, too vindictive, perhaps even impossible. “Data mourning,” then, surfaces as an alternative theorized by the architect and researcher Marina Otero Verzier. Coming to terms with the inexorability of digital decay, she suggests that we must let go of digital data that has become “redundant, outdated, or no longer needed. Just as we mourn the loss of physical objects, places, and people, data mourning recognizes digital data’s emotional and cultural significance and the need for new practices for letting it go.”

Perhaps. But first, we must stop believing.