“What will a human being be like who is not concerned with things, but with information, symbols, codes and models? There is one parallel: the first Industrial Revolution.”

—Vilém Flusser

Software ate the world. We, humans, are in the digestive tract of the global technological-capitalist organism, which Karl Marx identified as the capitalist mode of production and Vilém Flusser calls “the apparatus”. We are being metabolized by it. This is nowhere better reflected than in the form media consumption takes today: doomscrolling. This digital phenomenon, beget by the ubiquity of smartphones, is a neologism describing the pathological habit of consuming an infinitely scrolling feed of media content to the point of psychological self-harm. The following analysis will explain how the transition from desktop computer to capacitive touchscreen unlocks an all-new profit model which threatens human dignity and independence. These events are unfolding in a disturbing parallel to those of the First Industrial Revolution. Smartphones and digital platforms are the machines of large-scale industry in the twenty-first century. They bring about the real subsumption of the human spirit within the digital-capitalist mode of production. Its machinations impose a suite of gestures which individuals use to pursue basic social livelihood, but which simultaneously cause mass suffering and exploitation. This revolutionary model transforms a person trapped in its addictive cycle into a living being something more like constant capital than worker.

The Computer

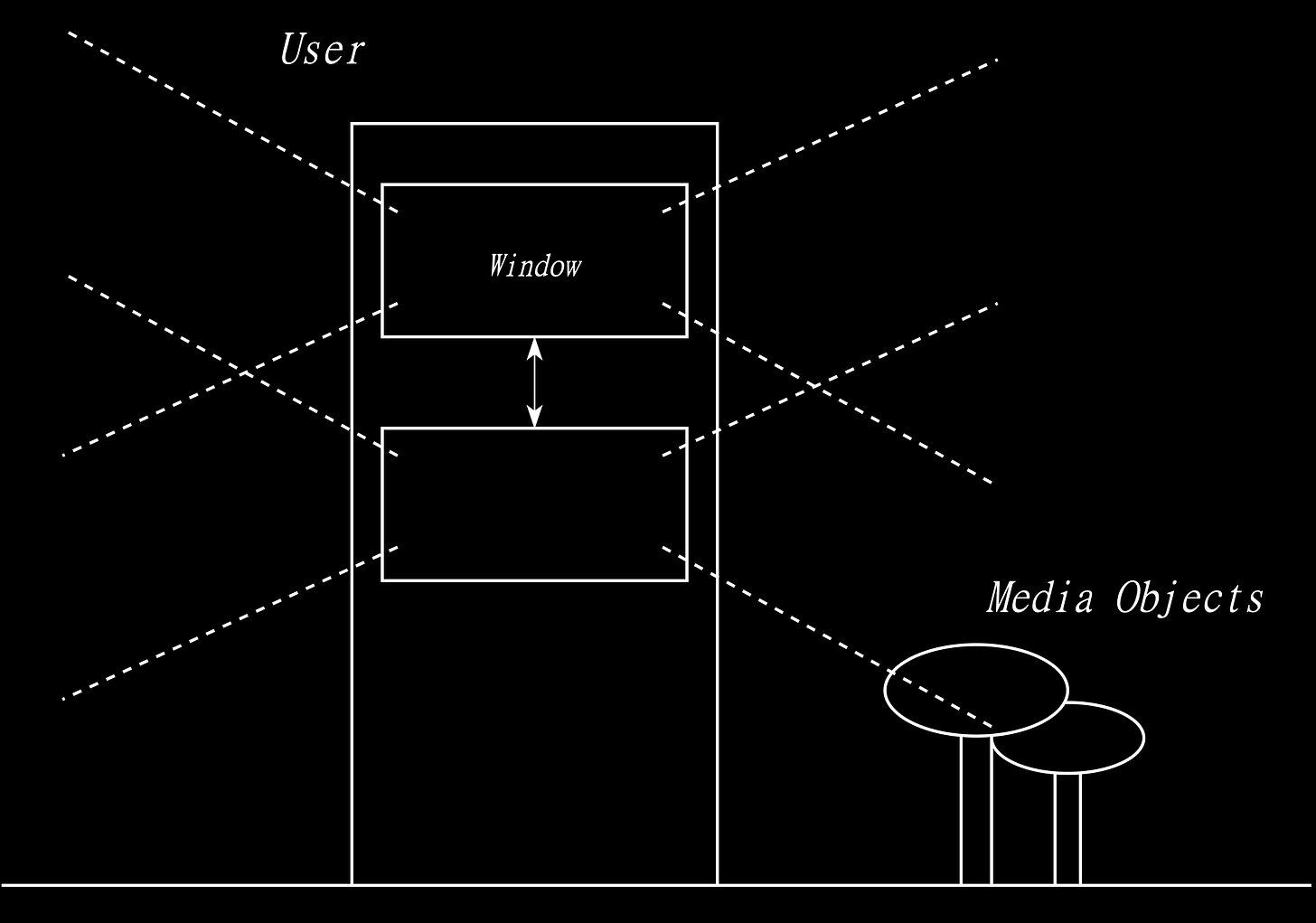

The computer, a stationary work-site consisting of a screen, keyboard, and mouse, is the appendage of the white-collar “digital bourgeois”: the Google employee or Worker’s Compensation adjuster. The screen is an analog for the page, the keyboard a digital typewriter, the mouse a stylus. The operation of such a system is an indirect brain-to-screen interface which requires coordination, skill, and dexterity. The use of the computer is mediated by a complex interplay of keys typed, mouse clicked, and screen read. Young children must be trained to type on the keyboard and many are not very good at it even into adulthood. If for Flusser the typewriter is the machine analog to the piano, the computer might be the analog for the orchestra’s conductor. Computer work is skilled and involves data entry, word processing, information management, logical reasoning, problem solving, programming, designing, innovating, and disrupting. Computer interfaces are made up of windows, entailing sight, visibility, horizontality. Its horizontal orientation is set in the aspect ratio 16:9. One can see through the computer as one can see a landscape through a high window. Its gestures are of freedom, breadth, expansion, perpendicularity, and boundless space. Such gestures are fundamentally a gesture of “searching”, which is concerned with the discovery, classification, and manipulation of inanimate objects. This is the nature of technocracy:

“Technocracy is the form of government of bourgeois ideologues who would turn society into a mass that can be manipulated (into an inanimate object) [...] It becomes an objectively perceptible and alterable apparatus, a human being an objectively perceptible and alterable functionary. Through statistics, five-year plans, growth curves, and futurology, society does in fact become an ant colony.”

—Vilém Flusser

Despite the fact that they inhabit the technocracy, individuals like programmers are still laborers who are exploited in their work on computers. Paradoxically, they now appear more closely like factory wage-laborers who operate the instruments of production to produce value. White-collar workers are churned into high-rise office buildings and back out of them again in remote work and boom-and-bust cycles. Computer laborers suffer from repetitive stress injuries: micro-tears, inflammation, and nerve damage. This is a tale as old as time. But this class, and the computer, is already a living fossil. They have been superseded by a far more efficient technology for generating profit: the capacitive touchscreen.

The Touchscreen

The capacitive touchscreen is a mystifying veil over the rational kernel of the computer. To touch a touchscreen is an oxymoron: you believe you are tapping a button but you are feeling nothing at all. What is feeling is the screen, abrim with energy and sensors. In fact, the screen touches you. The human body is electrically conductive because we are filled with fluid, and our cells filled with conductive ions. So a layer of conductive material is placed upon a screen, which generates an electrical field. When your finger approaches, this electrical field is drawn upward to touch your own. The screen’s highly sensitive capacitors read this disruption in its own field: capacitive coupling. The device’s processor analyzes the location of your gesture on the screen. It then decides how to react to you.

Touchscreens proliferated with the introduction of the Apple iPhone in 2007. The iPhone revolutionized the technology industry and subsequently the world, as Marx predicted. People now spend more time than they ever have before engaging in labor and economic exchange through smartphone apps. Such apps are designed to supercharge any person’s ability to participate in the economy, operate as a small business, purchase and sell commodities, or labor to produce data, content, and attention. This quantitative leap causes qualitative transformations in the social fabric, dialectically rippling outwards from Silicon Valley to the far reaches of wireless networks. The smartphone reorganizes social relations, disrupts and re-creates new modes of production, and exploits and dehumanizes “users” across the globe. Flusser says it best: “the hands have become redundant and can atrophy. This is not true, however, of the fingertips. On the contrary: They have become the most important organs of the body”.

The Doomscroll

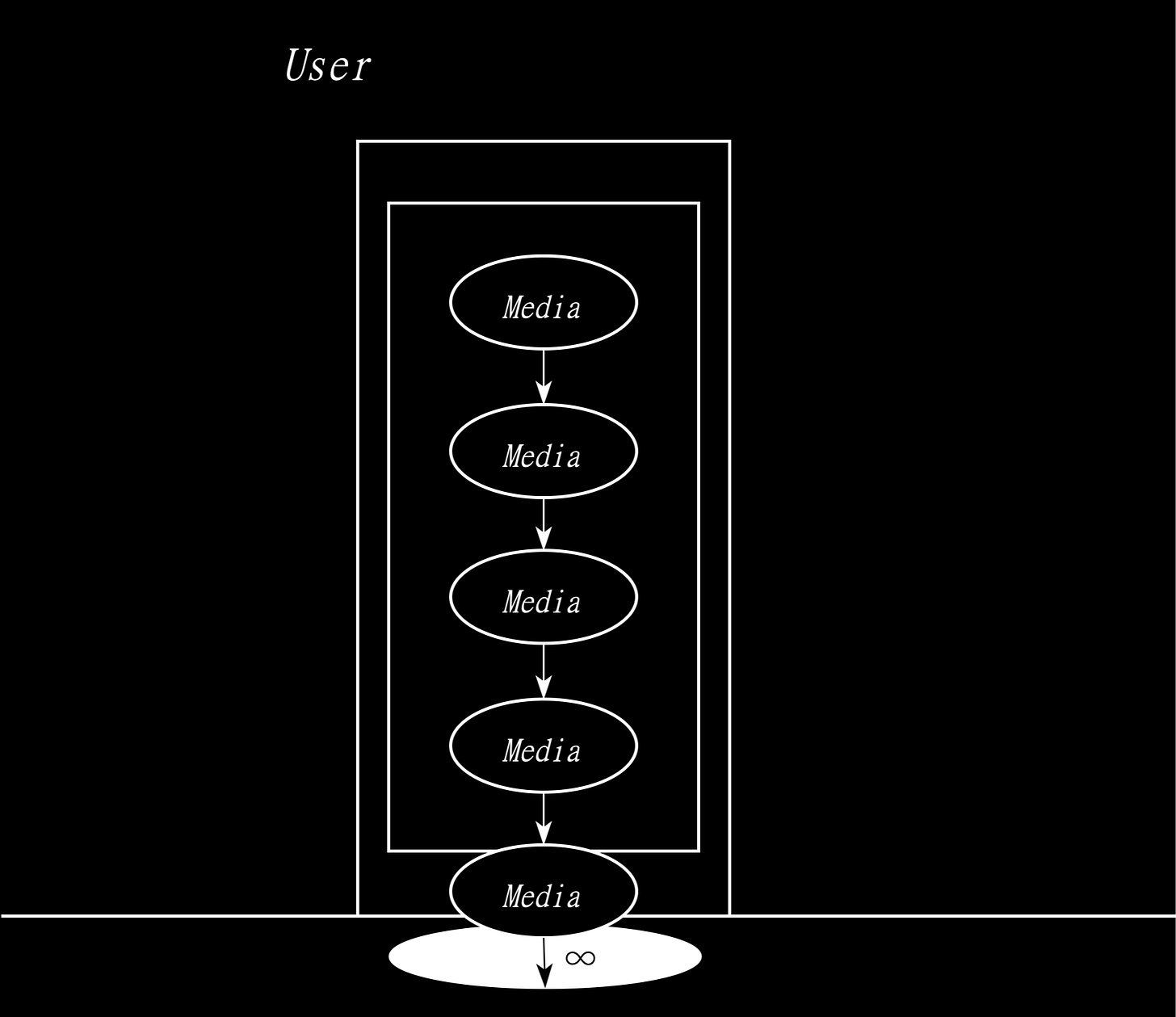

The way smartphones are used today is opposite in character to classical computing. The smartphone is vertically oriented rather than horizontal. Its aspect ratio is 9:16, and displays vertical photos and vertical videos. The person who touches its screen is hemmed into a narrow corridor in which they consume, or are fed, from a “feed” of media content. They move around by swiping (horizontal, limited) and scrolling (vertical, infinite). A scroll can only reveal information in small snapshots as it is progressively unrolled at one end and re-rolled at the other—tunnel vision. One traverses this scroll in a downwards direction of potentially great but unknowable depth, also known as a rabbit hole. But the hole is booby trapped. This vertical orientation is of limited space, it is confined, with no room for free articulation and only the ability to repeat over and over what came before—that is, going further down. It is narrowing and parallel to many others doing the same but never intersecting. When one finally “returns to the top” for air, it is with great force and rapidity, so fast they might experience whiplash. Confused and bewildered, they are free to go find another hole.

This is the gestural affect of doomscrolling, a neologism of the 2020s which describes the qualitative shift toward addictive and seemingly endless media consumption on technology platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. The infinitely scrolling content feed is the present apotheosis of mass media and the site of the vast majority of digital communications and information exchange. It is the next phase of real subsumption of what Tiziana Terranova described as “free immaterial labor” in 2000. It is evident now that the tech industry has unlocked the correct “virtual machinery” to enable the production of infinite relative surplus value. This machinery is based on vast data collection and machine learning algorithms. It works based on turning a relatively small percent of users into “small masters” who produce content successfully, with a very small shot at making a living. It entraps the totality, themselves included, in a vicious cycle of addictive consumption. The moral corruption of these algorithms are plain for everyone to see. Venture capitalists are eager to share their strategies, which they call engagement, stickiness, and retention, words which reference the “dark patterns” of enticement, capture, and imprisonment of users’ attention and life-force.

The conditions of the immaterial laborer are the opposite of the material laborer of the First Industrial Revolution. The deleterious effects on their person are by and large psychological rather than physical. As such they result in a degradation of a different sort. Where the factory worker of yore worked ten back-breaking hours in the factory before returning to his cot, our immaterial laborer is as materially comfortable as they could possibly be. Their life is resplendent with commodities, foodstuffs, and free time (relatively). So what’s the problem? The problem is that the encroachment of the working day on the immaterial laborer has put their mind to work for a period as long as they are not sleeping. This cognitively dulls the user and activates regions of the brain that are associated with drug addiction.It has resulted in imbalances and dysfunction of the neurotransmitters of the brain, impacting dopaminergic and serotonergic balance. They engage with their smartphone as shift work from the moment they wake up to the second they fall asleep, on and off, disallowing the full resumption of restorative activities. The excessive use of digital media platforms damages users’ ability to focus on tasks and perform the functions necessary to their livelihood. It has given rise to a never-before-seen number of ADHD diagnoses by online doctors.

It is clearly evident that smartphones and their social applications are diminishing the human brain and the human spirit. It is so unpleasant that its negative nature has entered common parlance (one of “doom”). It is a wonder there is no great struggle over its abolition, only more fervent uptake of its enmities. This fact alone speaks for the power of the psychosocial trance it holds society in. The most concerning question is that of future generations. Because immaterial labor is not widely considered to be labor, technology companies are free to infinitely exploit children. Marx wrote on child labor: “Now the capitalist buys children and young persons. Previously the worker sold his own labour-power, which he disposed of as a free agent, formally speaking. Now he sells wife and child”. Child and adult alike are subject to the machinations of the platform machinery. This is made all the more poignant by the fact that touchscreen devices are being used to distract and babysit infants and children by overwhelmed and overworked parents. Into the jaws of doom they go.

Users as Machines

The doomscroll’s seemingly infinite scale challenges existing associations between social media users and social media platforms, inverting the roles that people and machines play within the capitalist apparatus. In cyberspace, machine-learning algorithms are changing minute-by-minute. They are highly motivated to adapt to the minutiae of both the individual and the masses. They take on autonomous life and assume the user’s former horizontally expansive position. They communicate with APIs and data sources far and wide, across whichever platforms it chooses, subsisting on electricity to perform their labors. In the process, the apparatus’ value appreciates, undergoing constant training by its technocratic parentage.

Meanwhile, the user de-skills and becomes ever more dysfunctional and drooling. Attempts to understand the media consumer’s role abound: from Terranova to Fuchs to Zuboff, each variously positions the internet user as free laborer, producer-consumer, and data commodity. However, this range of analysis does not account for the compulsive, mechanical nature of doomscrolling. Marx’s “working day” formula falls apart at infinity; social media users’ psychic deterioration is the mechanism by which their productive value actually increases. We can understand this human-mechanical behavior by way of Flusser’s theory of machines:

“And if by “getting free of machines”, we mean not doing anything anymore, we are challenged by consumption, which is contained in the programs of the apparatuses [...] In short, beyond machines, there is nothing to do, for work in the classical and modern sense has become absurd. Where apparatuses prevail, there is nothing left to do but function.”

—Vilém Flusser

Flusser posits that work has become automatic and tautological—functioning for the sake of its own functioning. In other words, like a machine. Marx states that a portion of the instruments of labor acquire a social character. What if the instruments of labor have become social organisms themselves—people? Perhaps the real subsumption of a person immersed in a world of machines is their becoming a machine itself.

If we flip the roles, it is the apparatus itself which comes alive to produce relative surplus value by acting on a calcifying corpus of humanity. The human then takes the place of constant capital, waiting for some algorithm to pick them up and use them. Through the methods of gamification and strategies of engagement, stickiness, and retention, network lock-in effects, and other entrapment techniques, users can be psychologically groomed into value-producing machines. Ever more enthralling notifications and features can be endlessly devised to top up the oil of these organic machines. People are dispossessed and expropriated from their own minds and bodies. They are alienated in their transformation into an organic machine, only useful for its fingertips. These organic machines consume the chum that the infinite-scrolling feed throws into their maw, producing surplus value at a rate of 100% profit. All the deleterious effects of this are externalized to other parts of their life—to the management of their psychiatric symptoms by the pharmaceutical industry, their suffering and isolation, their executive dysfunction—so long as they continue tapping and swiping until their natural death or suicide.

☠