"they’re just like me, fr: characters, lore, participants"

curated by Kyle Mace

Andy Bennett, Christian Casas, Tibor Dieters, Drew Dubs, Rachel Jackson, Michael Louttit, Sam Radford, Boomer Scripps, Jake Siskin, Gabrielle Stichweh, Nick Vyssotsky, Lucy Weaver

The following is a reflection on a group show organized in Summer 2023 at Lambda Research, an artist-run project space in Cincinnati, Ohio.

“Once upon a time people were born into communities and had to find their individuality. Today people are born individuals and have to find their own communities.”

- “Youth Mode,” K-Hole, 2013

In December of 1893 in the pages of The Strand magazine, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle killed off his beloved character Sherlock Holmes. The story “The Final Problem” was intended to be the final story with the famous detective, wherein the plot culminates in Holmes falling to his death. What followed the story's publication was nearly unprecedented for a work of fiction: thousands of Londoners donned black armbands to mourn Holmes' death and many thousands more withdrew their subscriptions to The Strand, nearly tanking the magazine. In response to mounting public pressure, Sherlock Holmes' creator acquiesced and began writing new works featuring the famous detective. Through their collective efforts, one of the earliest incarnations of the modern fandom was able to resurrect the dead. 130 years later fandoms and their adherents continue to exert influence in the cultural sphere, only now this dynamic is accelerated to the brink, and at times has transgressed the boundaries between culture, politics, and the social.

The scenario that played out between Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the feverish adherents of the Sherlock Holmes series seems somewhat quaint today. Although this period in the late 19th century was witness to hastening developments in art and industry, it took some decades for technological development to intersect with the standardizing logic of capitalism to create something like a mass culture industry. In The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception Theodor Adorno argues that the cultural products within this industry are not authentic expressions of human creativity but rather commodities manufactured for profit [1]. With the advent of this new capitalist mass culture made available through the media ecosystem of film, television, radio, and print media, something like an oppositional culture with shared affinities built around discrete aesthetic practices and a desire for authenticity became almost inevitable. This ushered in a cultural dynamic that played out from the mid-20th century and well into the 21st: countercultural formations like beatniks, hippies, punks, and many more all served as foils to their mass-produced counterparts, only to be incorporated into that very same system via market capture.

Today, the glut of algorithmically recommended content on the platforms has all but flattened the distinctions between subculture and mass culture. It is a very real possibility today for experimental or ‘underground’ artists to exist in the same Spotify playlist as Billboard chart-toppers, and TikTok feeds routinely popularize some of the most unexpected songs and artists. Everything exists on the same plane, ready for instant consumption. This flattening process has the effect of neutralizing some of the potency of counterculture as a site for social organization around shared aesthetic practices, not because it widens the potential for participation, but because it engenders what writer and scholar danah boyd would refer to as context collapse, a phenomenon in which social media platforms collapse discrete social contexts, leading to the confusion and blending of a multitude of relationships and audiences in online interactions. [2]

At the same time, the spectacle of “mass culture” is becoming increasingly commodified. To some reading this, the “Funko Pop-ification” of culture is not a new phenomenon, but it warrants mentioning with respect to fandom and fan culture. Since the object of fan devotion often has its origins in pop culture, fandoms, and their activity constitute a neatly defined and pre-constituted market segment, and thus contribute to the limiting of the potential for this type of fandom to exert real influence on culture at large in any sort of transformative way. At this point in the development of capitalist mass culture, this relationship between cultural figures, their creative output, and the communities that congregate around the two is pretty standard fare. This type of relationship between the source material and the community can be understood as an Affirmational Fandom. Originally formulated in a June 2009 post by user obsession_inc on the journaling platform Dreamwidth, an Affirmational Fandom is one in which “the source material is re-stated, the author's purpose divined to the community's satisfaction, rules established on how the characters are and how the universe works, and [how] cosplay & etc. occur.” In other words, this type of formation is generally adherent to the original creator’s intent, and thus the object of cultural obsession retains its integrity as intellectual property [3].

Conversely, a Transformational Fandom is “… all about laying hands upon the source and twisting it to the fans' purposes, whether that is to fix a disappointing issue… in the source material, or using the source material to illustrate a point.” In a Transformational Fandom, all members have an equal opportunity to radically re-interpret the source material. This method of engagement with the source material has the potential to be far more antagonistic and willing to subvert notions of intellectual property than in an Affirmational context, and it is precisely in this potential—one that constitutes a kind of cultural détournement—that was one of the motivations for organizing the group show they’re just like me fr. Although more personal, other motivations for the show are of equal importance in the sense that they originate in some spaces that overlap with and are parallel to fandom culture.

Like many students in the early 2010s, I was an active user of Tumblr, by then already well-established as a microblogging platform for numerous fandom communities. Like many other users in certain corners of Tumblr at that time I happened to find the Jogging, which quickly became a focal point in my Tumblr browsing habits. I soon became enamored with many of the posters and artists featured on the blog, and although I never contributed myself, the impact of the Jogging on my internet-addled developing brain can not be understated. Fast forward ten years and the subcultural communities that initially drew me to Tumblr—noise and punk music—were brought to a near standstill by the global pandemic. With nothing but time and curiosity, I found myself mingling in what Yancey Strickler has termed the “dark forest” corners of the internet. Although they aren’t difficult to access in the way the dark web is, these online spaces also aren’t indexed by the big search engines either, they end up being a secret third thing. In some ways, this is what the internet as a whole is becoming: “In response to the ads, the tracking, the trolling, the hype, and other predatory behaviors, we’re retreating to our dark forests of the internet, and away from the mainstream.” [4] This process closely mirrors how fandoms found themselves congregating during earlier eras of Web 1.0 and 2.0, and like the radical potential of Transformational Fandoms, these dark forest communities of the internet appear poised not just to influence culture at large, but the social and the political as well. The dynamics of fandom already have begun to do so.

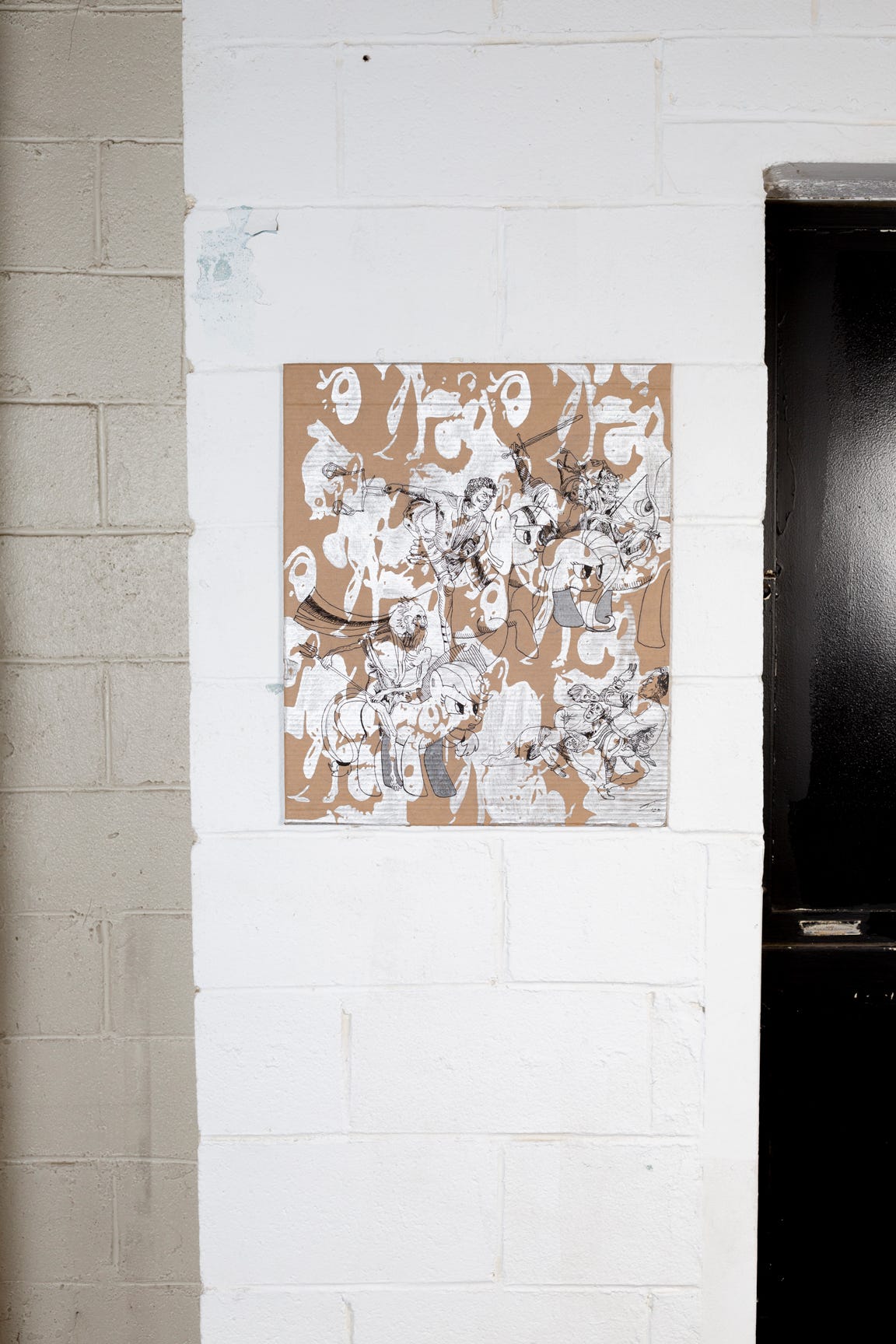

In many ways, I wanted to organize a group show around the idea of fandoms and fan culture because I see it as a dynamic that plays out not just in culture, but in political and social formations as well. I tend to sympathize with writer and internet culture researcher Katherine Dee’s analysis of political formations as fandoms when she writes: “My suspicion is that fandoms are just the organizing principle in a consumerist society. We live in a world of macro and micro fandoms.” [5]. However, this isn’t the only reason I wanted to organize this show. Perhaps more selfishly, I wanted to bring works from these artists together in one show because I am a fan of their work and the communities in which they operate, and also because I think that in varying ways their work addresses and expands upon the themes I’ve discussed above. For example, Boomer Scripps’ and Drew Dubs’ work in the show illustrates how adherents of Transformational Fandoms freely borrow from, remix, and recontextualize cultural objects from a multitude of sources in strange and unlikely ways.

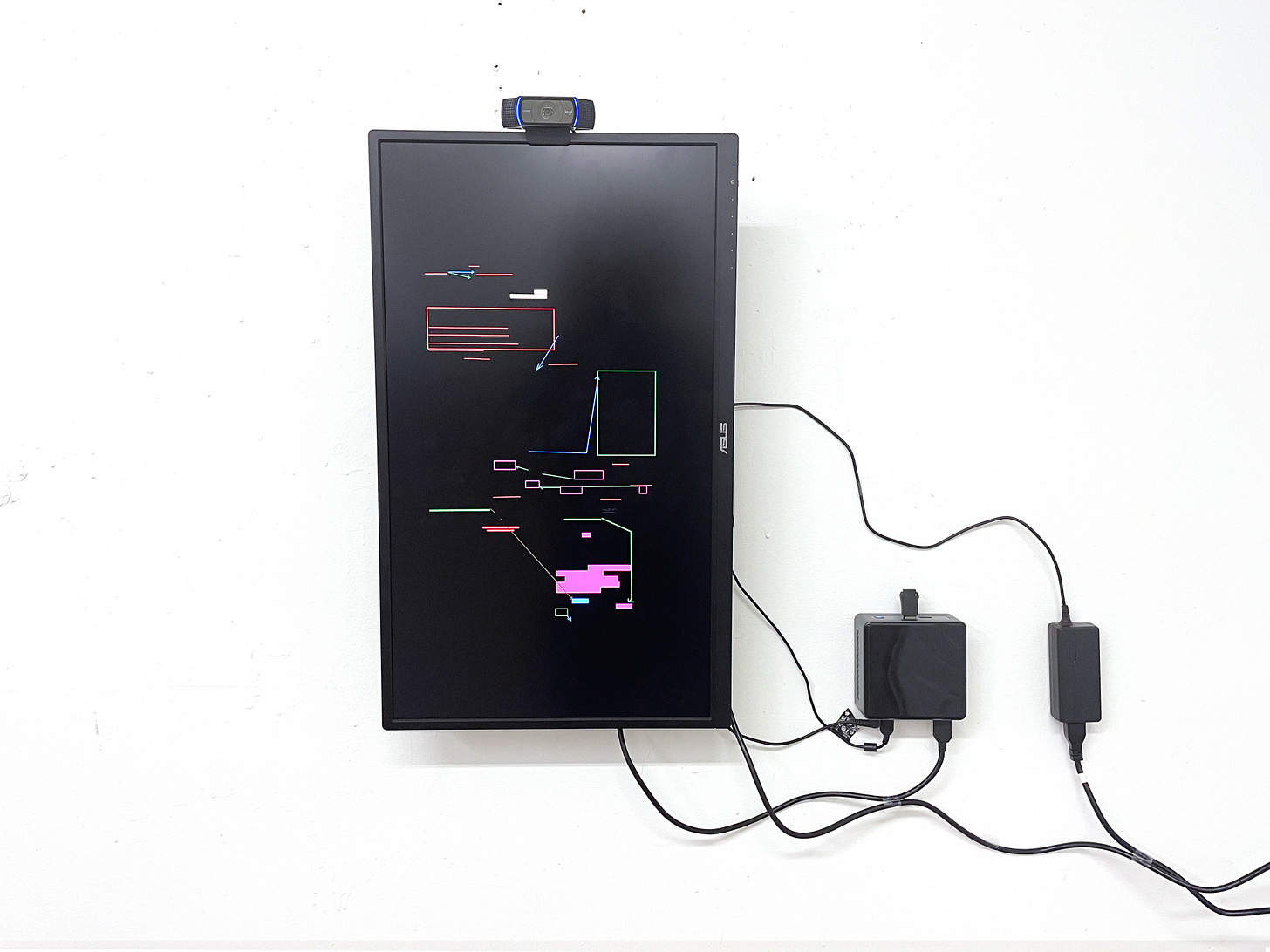

This same chimeric approach to cultural objects is utilized in the work of Andy Bennett and Nick Vyssotsky in the service of conjuring energies and manifesting spiritual/cultural egregore, a kind of non-physical entity that is made to have real world, physical effects through a collective practice of directing intentions not dissimilar from that of fandoms. The digital realm can be said to have similar magical properties. As Nadim Samman so rightly points out, the word “encryption” is built around the image of a crypt, which is “an occult place” that by definition, contains a body.” [6] In this sense, the work of Tibor Dieters, Lucy Weaver, and Rachel Jackson all explore from different vantage points this process of contemporary subject formation via encryption, decryption, and re-encryption, processes the fans often implicitly engage in as they translate their identities within and through cultural forms.

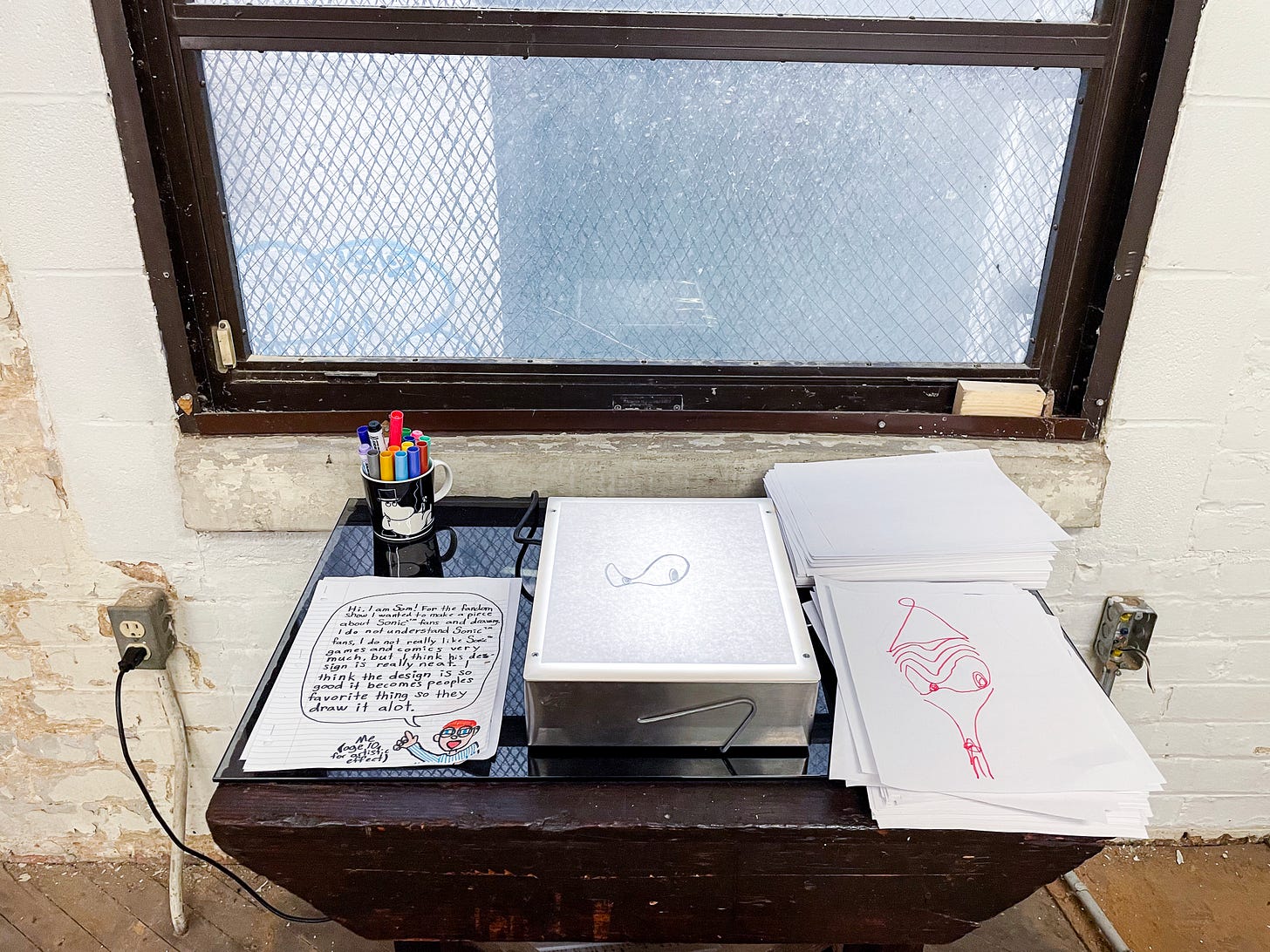

In a less esoteric (but surely gnostic) sense, the work of Christian Casas and Gabrielle Stichweh here examines how fandoms collectively and individually create their own lore and interior canon and how this maps onto ways of narrativizing highly spiritual and psychological events, either through an embodied revelation or through transcendental contact with the divine. Finally, the work of Levels of Nuance, Jake Siskin, and Sam Radford all engage with the idea of participation, something that is fundamental to Transformational Fandoms in particular. All of these works, either in their creation, presentation, or both exemplify the collective process of meaning-making and world-building that is so critical to the way fandoms have historically operated.

What I love about each and every one of these artists is the myriad ways in which they’ve been able to metabolize images, objects, and practices from a variety of cultural contexts and to create links with other areas of cultural practice. Each of the works in they’re just like me, fr speaks to the artists’ deep engagement with culture and subjectivity, and an ability to materially realize those experiences in truly fascinating and groundbreaking ways. I’m humbled to call many of these artists my peers, and to see them so ready and willing to work with me and one another on many, many projects before and after this show signals to me that I’ve truly found a community like no other.

Citations:

[1] Adorno, T. W., & Horkheimer, M. (1944/2002). Dialectic of Enlightenment. (G. Schmid Noerr, Ed., E. Jephcott, Trans.). Stanford University Press.

[2] Marwick, A. E., & boyd, danah. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114-133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

[3] obsession_inc. (2009, June 1). Affirmational fandom vs. Transformational fandom. Dreamwidth.org. https://obsession-inc.dreamwidth.org/82589.html

[4] Strickler, Yancey. (2019, May 26). The Dark Forest Theory Of The Internet. Ystrickler.com. https://ystrickler.com/2019/05/26/2019-the-dark-forest-theory-of-the-internet-1/

[5] Dee, Katherine. (2023, April 23). What do I mean when I say that politics are fandom? Substack.com.

[6] Samman, Nadim. (2023). Poetics of Encryption: Art and the Technocene. Hatje Cantz.

Just now coming across this well written and great post. My work right now is expanding on identity and distributed cognition in virtual spaces. This curation seamlessly weaves those ideas into our physical space. And I’m from the dark live journal and tumblr generation of subculture, so also feel.