Ryan S. Jeffery: Duds of Dominance

Ryan S. Jeffery is an artist and filmmaker.

Part I Soft or Hard Revolutions

Ever since OpenAI dropped its first demo of ChatGPT, debates have raged over whether so-called generative AI is an actual paradigm shift or just energy-sucking snake oil. However, in the background, a consensus quietly formed that I believe marks a break in how digital communication technologies have historically been considered vis-à-vis the material world. For the past two decades, a foundational myth for Silicon Valley has been to paint cyberspace as an ephemeral nonplace that can be seamlessly interfaced through powerful, ever-slimming devices. This began as the software revolution, as profound as the agricultural and industrial ones before – or so we were told. But despite the dictum of Moore’s Law, left out of the picture was that as the devices in our hands became increasingly lighter, the massive infrastructure to make it all run grew corresponding heavier somewhere else. Cyberspace, it turns out, takes a significant bite out of meatspace.

Ten years ago, curator and researcher Boaz Levin and I made a film about this by mapping an incomplete survey of data centers, or the internet’s “backbone.” Our intention was to show how these wonderous architectural machines of tomorrow were not some profound break from the anachronistic infrastructures of yesterday but rather a resource hungry albatross around already rickety power grids. Consider the term “energy transition,” originally promoted by energy companies to stall changes to existing carbon-burning infrastructures and ultimately obviate replacement – in other words, to do exactly the opposite of what the term suggests. Likewise, the clever branding of “the cloud” could hardly be more disingenuous. As technologist Dwayne Monroe succinctly puts it, “Computation is an industrial process.”

Much of the ire around the energy consumption of computational infrastructure picked up on the massive amounts that crypto mining uses. Thus, when DALL-E and ChatGPT splashed onto the scene, spitting out images and texts to showoff large language model (LLM) technologies, the environmental costs were quickly pointed out. Nevertheless, AI hype has continued to spur a data center boom, now branded as “hyperscalers,” and just in time for the arrival of some of the most dramatic effects of climate breakdown. This has already led to mounting confrontations between local communities and tech companies over issues of water rights, spiking energy prices and even rolling blackouts – to say nothing of the increased frequency of destructive storms battering infrastructures. Perhaps logging off will increasingly be a choice made for many of us, as both Hito Steyerl and Dehlia Hannah have recently suggested.

But not so fast! Power brokers like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel and Sam Altman are doing all they can to keep the hype hot, best illustrated by their advocacy for a return to nuclear power. Even former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, a stalwart bridge between the tech industry and the nominal progressivism of the US Democratic Party, scandalized many with some flip comments about the acceptable tradeoffs between ecological disaster and humanity’s need for AI technologies. Indeed, the mask is off: Power in every sense of the word is what’s at stake. Whether by heating up nuclear rods or heating up the atmosphere (likely both), the only option on the table is to plow ahead. Besides, after they’re built, the machines will tell us how to fix our mess.

The myth of weightless ethereal tech appears to have run its course. Time for some new myths. How about a new industrial revolution? This is what Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang is pitching. Not quite a household name, Huang has managed to stay out the fray from the culture wars engulfing the Silicon Valley C-suites. Yet he may represent big tech’s material turn better than anyone – Musk’s big rockets and trucks included. Where OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, the face most arguably associated with AI, still rears into the old ephemeral language of an “Intelligence Age,” in the vaguest of terms. Huang speaks like a soot-stained industrialist for the twenty-first century, going as far as to refer to his “fabless” microchip company as “a foundry for AI.” At the launch of nearly every Nvidia GPU processor since 2020, Huang has repeated the refrain: “The data center is the new unit of computing,” effectively thrusting the backstage magician’s assistant out front to finally take the prestige. This vision of technology scales in two directions: beyond the limits of human vision to the nanotechnology inside the chip, and the massive stadium sized data centers packed to the gills with these chips. Behind Altman’s abstract epistemological promises of AI is the concrete political economy of “Jensanity.”

This material turn in Silicon Valley’s self-conception is a full circle moment for Huang and his Nvidia cofounders, who as legend goes, in 1993, made the counterintuitive decision at a Denny’s in San Jose to focus on graphics processing for videogames. Three decades later, this gambit on hardware paid off. Once considered a juvenile market far from the serious business of software, the video game industry is now larger than the music and movie industries combined. Cracking the intensive computational challenges of graphics processing, subsequently paved the way for Nvidia to position itself as a driving force of hardware acceleration, and today’s AI boom. From gaming to crypto, the metaverse (or the omni) and now AI, Nvidia and Huang are always at the center. All of this is owed to the robust processing power of Nvidia GPUs which have played a crucial role in enabling the aptly named, “brute force” computational methods behind AI technologies. Wall Street has rewarded the company handsomely for this, with Nvidia in a constant back-and-forth with Apple as the S&P 500’s top holding. Indeed, whether it’s the properties of physics and engineering or market competition, dominance is afoot.

Part II Dominant Threads

Here I want to turn attention to a seemingly innocuous affectation amid this entire AI spectacle: Jensen Huang’s signature leather jacket. Calling back to the Boomer rebels of yore, Huang’s ubiquitous jacket is the gearhead counterpoint to Steve Jobs’s black turtleneck, another iconic fashion object from the ’50s underground. But where Jobs’s beatnik uniform spoke to the creative expression that software might unleash, Huang’s leather sides with hardware. Dressed in dramatic industrial goth and often dwarfing Huang, the very physicality of Nvidia’s imposing machines have the effect to overshadow any particular task they might do. These machines are big and they go fast. Mute the volume for Huang’s product demos for each new GPU box, described in dizzying microarchitecture specs, and it all resembles the unveiling of a muscle car. (The trendy rebranding of software as an engine, is itself an analogy to the car engine.) What you can do with this technology is superseded by the prowess of what it can do: it’s what’s under the hood that counts.

Huang has not been coy about his image-making, stating how he wanted to be known as “the guy in the leather jacket.” (The style pages and the financial press alike have taken notice. One $9,000 Tom Ford jacket cost the equivalent of approximately 10 shares of Nvidia stock at the time Huang wore it for a keynote.) A tech CEO attempting to flip the script on the nerd / cool dialectic is not exactly unique, as Ben Tarnoff insightfully unpacked from Walter Issacson’s biography of Musk. For Tarnoff, a particular masculinity defined by domination is key to understanding Musk and his “hardcore” drive. But this could be extended to the business culture of Silicon Valley writ large, which has long defined itself around the dynamics of creative destruction and the twined forces of entrepreneurship and competition, best described by Joseph Schumpeter. Huang must navigate these waters too.

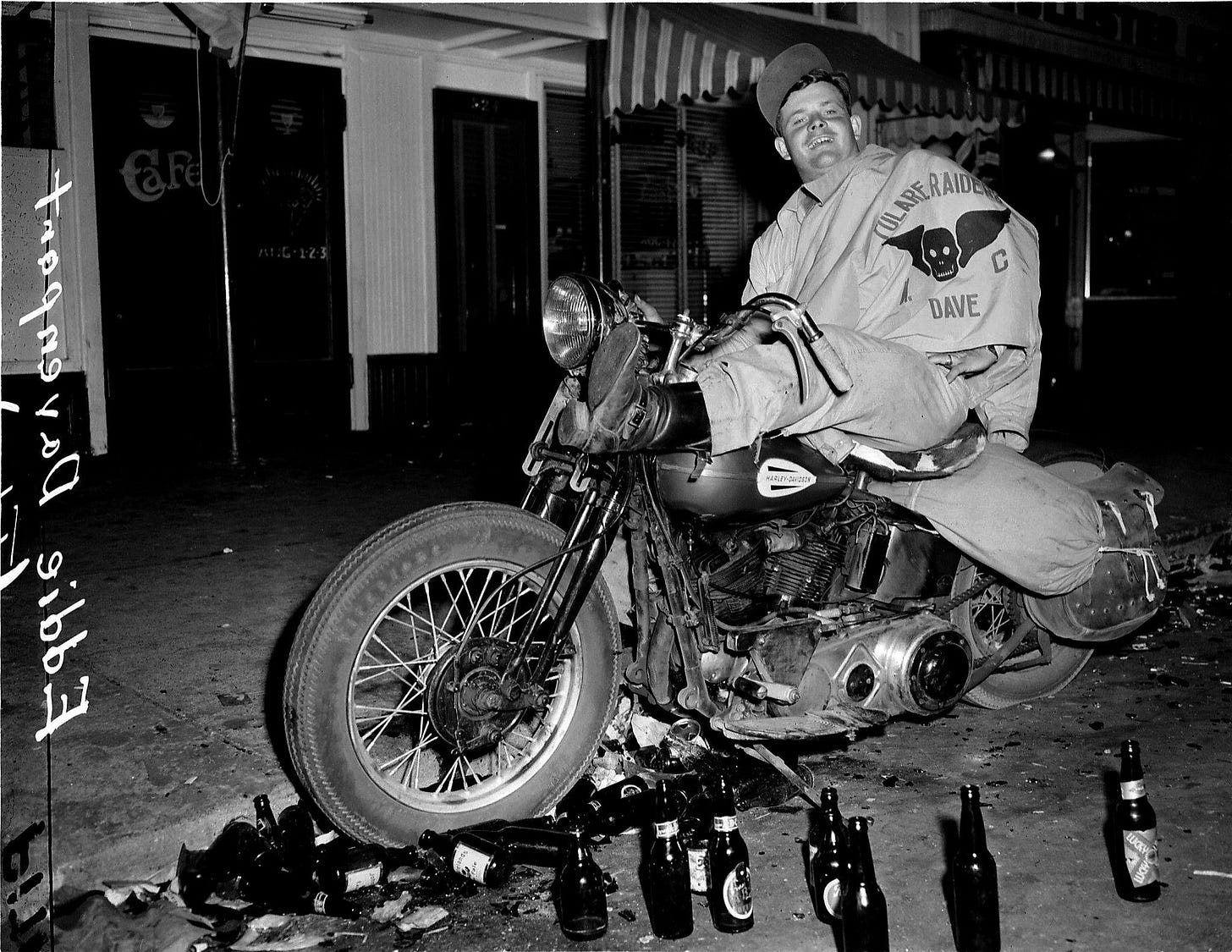

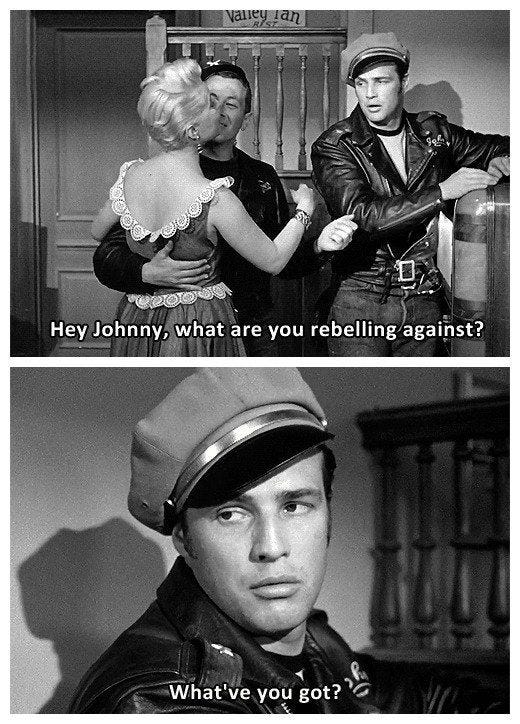

The leather jacket’s journey of identity and deviance, from Marlon Brando in Lászlo Benedeck’s The Wild One to Robert Mapplethorpe in the leather bar Mineshaft, begins where most everything else does in American culture – the military. The antecedent to the leather biker jacket is the pilot’s leather bomber jacket from both World Wars. Returning from the second World War, US veterans kept their bomber jackets on as a form of silent solidarity in their reentry into society. But for some, assimilation proved to be too much. Men’s motorcycle clubs offered an alternative community built around the male comradery experienced in the military. In turn, the motorcycle provided a sense of autonomy (both figurative and literal) from the malaise and trauma that so many carried back from war. The nose art of pin-up girls and violent, jocular humor that bomber squadrons painted on their planes reappeared on the back the biker. Born out of a context of state mobilization, the leather jacket transformed into the mark of the outlaw. But despite the desire to escape the mainstream, the leather jacket ran right back into it in Hollister, California in 1947. This was the infamous Hollister Invasion, when approximately 4,000 bikers overwhelmed the small town for a rally. A photograph of a drunken biker captured the debauchery and graced the pages of Life Magazine, causing a moral panic and the inspiration for Benedeck’s famed biker movie, with the square-jawed Brando as its leather-clad anti-hero. Celluloid sealed the jacket in rebel history.

In his book The Descent into Man, artist Grayson Perry devotes a short passage to the role of the leather jacket in his own identity formation as young man: “When he dons a uniform, a man takes on a bit of the power of all men who wear that uniform. When I first donned a leather jacket, I was very aware of the reputation that bikers had… Whenever I donned my leather jacket and kicked my bike into life, I was taking on an antisocial role.” Perry is keenly aware of the contradictory dynamics at play between identity and authenticity, noting how the uniform of the jacket elicits a particular type of performativity. Yet he also cannot help but lament the jacket’s loss of connection to a particular subculture and its descent into empty streetwear, also declaring how “Someone wearing a leather should have faced down the dangers of riding a motorcycle at speed and not just been shopping for vintage vinyl.” What Perry is in fact lamenting is the coercion of transgression into a symbol of status – the familiar story of counterculture’s reabsorption into dominant culture. Through this lens, Huang’s leather jacket can be read as just another defanged signifier of transgression, worn not to challenge hierarchies but to preserve them. This fits neatly into the story of Silicon Valley that historian Fred Turner tells in his book From Counterculture to Cyber Culture. The leather jacket becomes the CEO’s latest uniform, interchangeable with a grey suit or a grey hoodie.

Part III Machines of Libidinal Grace

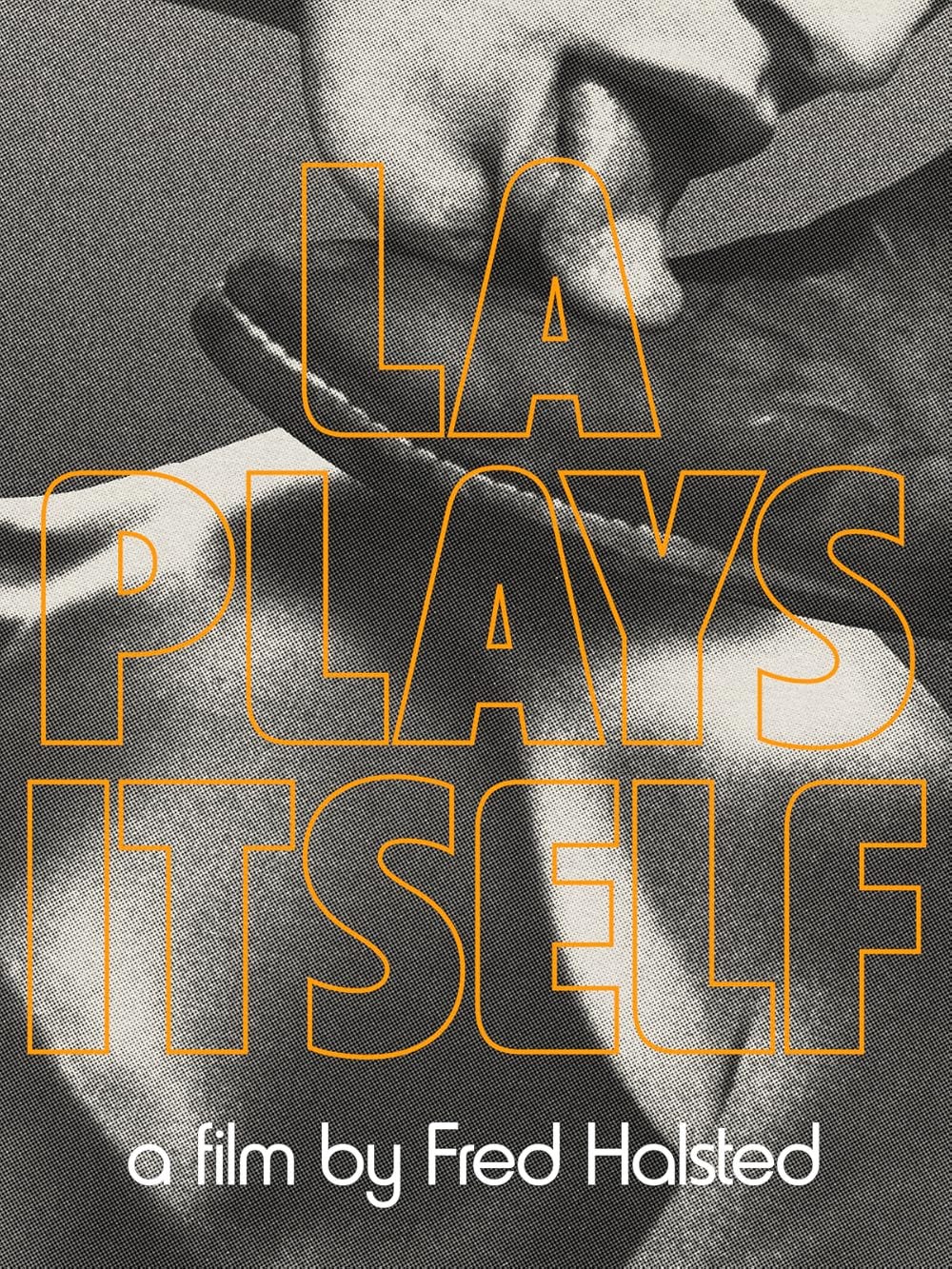

No matter how thoroughly the leather jacket has been appropriated for the libidinal economy, before it was fashion it was safety equipment. Whether in a military war or a culture war, the leather jacket was originally made to protect the human body at the critical threshold between machines and the environment by effectively wrapping the human body in a nonhuman skin. A relatively unknown experimental pornographic film made in 1972 might be the most insightful portrait of the jacket’s transition from equipment to fetish object, with the role of the machine as the catalyst. Shot in grainy black and white with no dialogue, Fred Halsted’s 35-minute Sex Garage takes place almost entirely in a run-down auto shop. The film’s plot comprises three acts of mounting transgressions, from acts of heterosexually to bisexuality and homosexuality. But the film does not conclude there. Rather, it ends with human and machine in sexual intercourse. Relying heavily on microlens photography and montage, images of human flesh, machines and chromed car parts are all given near equal screen time. The film’s attention often drifts to the shop’s walls, away from what’s occurring inside. The camera glides past lifeless machines, discarded equipment and pin-up posters, which all appear to bear witness to the cultural taboos being broken within this industrial site.

The effect underscores the juxtaposition between the garage as a deactivated site of labor which has been transformed into a site for carnal pleasure. To contemporary eyes, it’s tempting to read much into the year of the film’s production, 1972: the eve of the oil embargo, energy crisis, stagflation and acceleration of de-industrialization. In the film’s third act, the tone shifts with the arrival of a leather-clad biker. He joins the two men having sex, which gets more aggressive. Acts of domination become more prevalent: the biker stands with his boot on his partner’s back, their head is put into a toilet. But in the final moments the biker turns his desire away from his human partners to his motorcycle, which he copulates with through its exhaust pipe until he ejaculates on its leather seat.

The film does not end there, however. Adhering to the conventions of the three-act structure, the musical score moves away from a disjointed form of music concrete and returns to the gentle piano it began with. The viewer is taken out from the garage to the everyday, “normal” world. A rapid montage of anonymous people entering their cars flashes until settling on a long shot of a familiar congested city highway. The cars inching along are now no longer just cars. They are defamiliarized machines charged with erotic energy – the release of which we have just witnessed. Of course, the car as a machine of libidinal power is precisely an image that Madison Avenue has gone to great lengths to construct. Halsted’s greatest transgression might be seeing that desire through to its literal conclusion. By indulging in the fantasy, Halsted’s film underscores just how fundamental an ingredient domination is within the dynamics between human desire and the machines humans build.

The entanglement between technology and human desire is hardly novel. As most any media scholar will remind, the history of pornography is also the history media and vice versa. But can anything be gained by looking at Huang’s jacket with same ambivalent mix of seriousness and absurdity that Halsted applies when, after thirty-five minutes of crescendo and climax, he plops the viewer in with a multitude of “normies” creaking their way across the bloated motor infrastructure of the American Century?

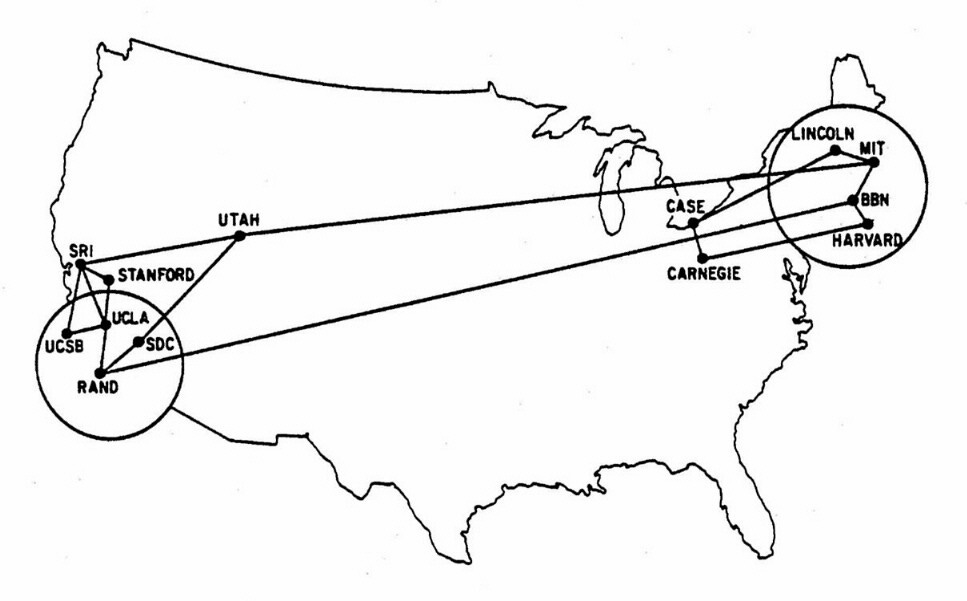

In 1968 Robert Smithson proclaimed, “The city gives the illusion that earth does not exist.” A pioneer in the land art movement, Smithson was fascinated by the anthropocentric drive to impose an order onto the earth – and the futility of such an imposition. He wrote these words about the persuasive power of the city landscape over two decades before the internet’s commercialization in 1993, but only a year before the establishment of ARPANET, the forerunner to the modern internet which linked the University of Utah, UCLA and Stanford University. Utah has been a critical site for networked technologies, home to the “Golden Spike” that linked the transcontinental railway, and then the “Golden Splice” that would go onto to link global communications systems. (Not coincidentally Utah was site chosen for Spiral Jetty in 1970) To a contemporary view, the often extractive and violent interventions of the land art movement, Smithson in particular, is a provocation over the ways in which the landscape is always marked by human activity. This is best captured by Smithson’s notion of the site / nonsite, which at its simplest could be described in terms of here and elsewhere. Smithson insists that between the site and nonsite resides a way to better understand how humans shape their environment and in turn are shaped by it. Through the lens of this particular dialectic, we can see how the city as a machine that offers the illusion of the earth’s erasure, becomes the ideological onramp for the myth of cyberspace as an illusionary nonsite as well.

A recent study determined that data centers have now overt taken the airline industry in carbon emissions. The myth of weightless cloud computing has vaporized. Huang’s leather acknowledges this, conscious or not, but it also reveals a certain recognition to the charge leveled by Smithson: a persistent desire to transgress against the dialectic of the human entanglement with the earth. To snap it in half and at last make it a one-way relationship of domination. More so than Smithson, perhaps Julius Von Bismark’s Punishment Series comes closest to the mark, in which the artist traveled the world to “battle against nature” by whipping the landscape. In the face of rapidly accelerating climate destabilization, marshaling the earth’s resources in a corporate, military and geopolitical race for AI dominance is a violent audacity that might just boil down to lashing the earth. Considering the leather jacket’s storied relation to both domination and alienation, then perhaps on the back of a tech CEO and one of the world’s most powerful AI evangelists is exactly where it belongs.

Awareness of positioning in the human hierarchy arises mainly for two reasons. Conditionally, position in your society is a remunerative and social outcome. It's a determinant of your survival. Then there is much attention given over to those who don't make it as an aberration that results from the loss of potential of human nature. It is almost a justification for the need to play the game as if the game really is justified. Most of that as structure is found in Game Theory anyhow.

Is there then a solution to both the game and those aware of it. Joseph Heller reflected with Catch 22 the nature of people, civilisation, human organisation and scaled activity is chaotic, destructive. Yossarian as the existential problem. Unlike any post war work before it (cp) solution was proffered in the very being of Dostoyevsky's apparent failure of the Underground man. A conditional yet, once understood, necessary compunction irrespective of the fact societal dependency is a realist truth. Orr as the phenomenological solution.

You can spend one's life as an academic, as someone with wisdom or with insight into the world around you, even better as all three. To observe and understand is still insufficient. To be is the solution - check with Orr.

Came via Quinn Slobodian's Blue Sky link.