LARP refers to “live action roleplaying”, a genre of roleplaying game where a fictitious world with its own lore and internal logic is mutually agreed upon by multiple players. Each of these players acts out a character within this world and, through their characters, engages in dialogue with one another. Perhaps the archetypal example of LARPing describes the sorts of historical re-enactments one would find at a mediaeval fair, but the term has been used with increasing frequency to describe people’s relationships to extreme political alignments. This essay is an inquiry into why LARP has become so resonant for understanding the aesthetics of specific political and cultural phenomena in the 21st century.

After Farce

Marx’s famous introduction to the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte—that history happens twice, first as tragedy, then as a farce—has become something of a leitmotif in the works of artists, cultural critics and journalists grappling with the absurd elements of political agitation in the 21st century. Notably, Hal Foster poses the question “What comes after farce?” in his 2020 book of the same name; a book cataloguing contemporary art responses to existence in the Trump era. However, with its renewed appeal, and with support from numerous textual and visual examples, a new addendum has emerged: LARP comes after farce.

The notion that LARP historically emerges after farce is incapsulated in a quote found within A.M Gittlitz’s biography of Homero Cristalli, better known as J. Posadas.

“What we on the Left flatter ourselves in calling our political and even our revolutionary work is in fact nothing of the sort. It is more akin to religious ritual. Mass rallies, newspaper sales, endless meetings, electoral campaigning, street fighting, writing articles that no one will ever read and books absolutely no one will ever get any practical use out of … In another time, in another place, these rituals may have had a relationship to a broader movement, a broader strategy, and such stirrings have always accompanied revolutionary moments. And so, having no real conception of the thing itself, we try to grasp at revolution by playing out its inessential weirdnesses ad nauseam. This is what comes after farce. This is LARP.”

This quote comes from Comrade Communicator, the incumbent leader of the Intergalactic Workers’ League – Posadist (IWL-P). The IWL-P is a predominantly online collective situated somewhere between political organisation and meme page, and they are some of the contemporary torchbearers of the legacy passed down from J. Posadas. Posadas was an Argentinian revolutionary whose chief conviction was to advocate for nuclear war as a tool of communist accelerationism. A further influential legacy of his political ideology was the conviction that if advanced extra-terrestrial lifeforms exist, they must have already reached communism, as it provides the only path for organising production towards the technological level necessary for interstellar travel. It's evident from this quote that Comrade Communicator is acutely aware of the arbitrariness – and absurdity – of deciding to be a Posadist in the 21st century. LARP here refers to playing out political actions empty of their capacity to materially advance an emancipatory project. And without these broader material goals, what’s stopping you from being a Posadist?

LARP is not exclusively used to describe left-wing revolutionary politics. In her exhibition titled ‘First as tragedy, then as LARP’, Tomi Faison riffs on the same theme to draw attention to the rioters storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021. For Faison, this turn of phrase was helpful to describe the fact that these rioters, after successfully breaching the Capitol Hill building, were forced to come to terms with their complete inability to do anything revolutionary after the fact. Insurrection becomes reduced to banal vandalism and bizarre photo-ops. Or, as Faison puts it, “they were only able to generate images”.

Many contemporary movements and organisations across the political, ideological, and spiritual spectrum still sustain membership, often composed of those that appear deeply passionate about their chosen cause. This sits in tension with the deeply held belief that under neoliberal capitalism, things will not change. The seeming incapacity to realise a political project beyond neoliberal capitalism was aptly described by Mark Fisher in Capitalist Realism. Fisher argues that any desire for systemic change in the world is placated by living vicariously through fantasy representations of people enacting these changes for themselves. Fisher argues that Capital will always find a way to co-opt revolutionary desire and sell it back to you, often in a defanged and harmless form. To illustrate this point, consider for example the merchandising of Che Guevara’s image on t-shirts, the Guy Fawkes mask, even the Hunger Games or Black Panther movies. Dale Beran, in It Came From Something Awful argues that by being surrounded by this co-option of political aspiration by capital, we are left with the sense that our subjectivity has been reduced to being a consumer. Therefore, all that we find ourselves able to ask of our political imaginary is that we have media representations available for our consumption that reinforce and signify our political ideals and display our ‘revolutionary’ identity brand.

A major consequence of the phenomenon described by Fisher and Beran is that revolutionary politics beyond neoliberal capitalism evolved into politics being adopted as personal style and performed regardless of their efficacy. In The Trump Effect In Contemporary Art and Visual Culture, Kit Messham-Muir and Uroš Čvoro pinpoint the historical context for this political moment. They attribute it to the political condition that emerged in the thirty years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, described by Francis Fukuyama as the ‘end of history’ wherein technocratic, liberal, democratic, free market-based economies would become the inevitable end state of human organisation. Rather than post-ideological neoliberalism becoming the uncontested structure of the new world order, however, Messham-Muir and Čvoro describe the current period as one defined by “embodied, experientialist, regionalist, biological, biopolitical” identitarianism. Here, much of politics becomes attached to, and reduced to, self-expression through images.

The condition where widespread dissatisfaction with neoliberalism is met with the performance of politics for its aesthetic value and consumption within a wider capitalist framework is the condition where political agitation performatively gesturing towards revolution is described as LARP. Describing political agitation as LARP suggests a more complicated relationship between images and reality than to simply decry these political agitations as naïve and disconnected – indicating a deeper and more considered set of logics and motivations. I argue that the complicated relationship between images and reality suggested by the phrase ‘LARP comes after farce’ can be understood by examining it according to Baudrillard’s notion of simulation and hyperreality.

Baudrillard published The Precession of Simulacra in 1981, to address the impact mass media had on the subject’s experience of the world. Rapid developments in digital technology during this period enabled society to be saturated by photography, advertising, and televisual images. For Baudrillard, this meant that a radical shift had occurred between the late 19th and late 20th century in terms of what gave objects their value under capitalism; for the masses, objects became valued and desired primarily in terms of image and aesthetic rather than for utilitarian function. The rise of commodity fetishism and the dominance of image saturation informed Baudrillard’s claim that the real could no longer be directly accessed because it was entirely obfuscated by simulacra; instead, we could only access a simulation of the real. Epitomising this in the 21st century is the emergence of parasocial relationships and the sense that interactions between people online are more accurately interactions between each other’s images of themselves.

The Precession of Simulacra belonged squarely within the category of postmodernist thought which, according to Frederic Jameson, seemed to be inclined towards an “inverted millenarianism”, theorising the pervasive sense of an imminent end of everything, and the replacement of the depths of authenticity, essence and signification with the flatness and superficiality of appearance. The sense that this theory had reached a logical conclusion for cultural analysis gave way for Andreas Huyssen to regard it with suspicion. He criticised it as cynical and unhelpful for the way that it precluded any attempt to understand media representations according to their ideological functions. Arguably, the decades following proved this to not be the case; rather, I argue, the ways in which media represent ideological signification had become extraordinarily abstract, superficial, and protean.

In spite of allegations of cynicism, Baudrillard’s theory of simulation proved to be remarkably prescient, providing an effective framework for understanding the cultural impact and function of the internet as a ‘virtual world’. The utility of returning to Baudrillard today is not because he produced any kind of ‘end of theory’, but because in the forty years since theorising the supremacy of appearance and image in the way we understand culture, appearance and image has been reimbued with complex signification and depth of meaning. The advent of meme culture, for example, demonstrates the vernacular and communicative function of images which bear no indexical relationship to the dense meaning they convey, and yet, are understood and disseminated by people on an almost first-language basis. I will return to the relationship between the internet and simulation later on, but this relationship is central towards understanding the resonance of ‘LARP’ as a descriptor of political action.

LARP and Hyperreality

LARP implies a dual existence of a world of images and a world of the real. The world of images is self-contained, self-referential, and cognitively separate from the world of the real upon which it is overlaid. In order to LARP, one must physically participate in the world of the real, and cognitively engage in the world of images. LARP also implies a specific mode of engaging with the image world distinct from mere spectatorship: LARP is active, not passive. It places the LARPer in the dual position of actor and spectator to the image world. The person who LARPs creates their own alternate reality, and importantly, is aware that it’s ultimately just fantasy.

The dual interface with the world of images and the world of the real allows us to consider LARP in terms of Baudrillard’s concept of simulation. For Baudrillard, a simulation is a mimicry which threatens the difference between the real and the imaginary. A simulation, in every sense, operates in the world of images; its internal referents bear no relation to reality, only to other images. Consider the mediaeval fair: people parade as knights in chainmail, as jesters or as paupers, walk in and out of carnival marquees and sell each other a variety of handcrafted wares. The aesthetic expectation from going to a mediaeval fair is not that it accurately resembles mediaeval Europe—the aesthetics of which we can only comprehend in terms of an imaginary often based on stereotypes and mythology—but that it resembles every other mediaeval fair you’ve been to. Nevertheless, LARPing, like any simulation, always requires interfacing with the real at some point. At the mediaeval fair, LARPers will don capes and joust with wooden poles. The jousting might belong to the world of images, but the physical consequences of such actions can be very real.

If we consider through this lens the reworked Marxian adage central to this essay, ‘LARP comes after farce’, we can infer two things. Firstly, we understand that the political agitation within its scope exists as a repetition and emulation of a prior political agitation. We can consider repetition to be analogous to mimicry, re-enactment, or copy. Secondly, we can infer that it describes a political agitation situated in the world of images. The repetition of an event is a two-fold operation; it operates materially via its interface with the real, and it operates symbolically via its interface with the prior iteration of itself – its referent. For the repetition to be described as farcical, its purchase on the real is humorously undermined by its failure to convey the gravity of its precedent. However, to describe a repetition as LARP denotes another layer of abstraction; it denotes a repetition which can only ever reproduce its precedent symbolically, and whose interface with the real is experienced as jarring and inadvertent. LARP suggests that this third repetition is no longer situated in the real at all – it belongs to an imagined realm of simulation and is made possible by the social condition of hyperreality.

Hyperreality for Baudrillard describes the condition of late modernity where simulacra have become so pervasive in our everyday experience that the boundary between image and reality has become pointless to distinguish. Without a clear distinction between the real and the imaginary, simulations seem to be able to convey more meaning than the banal real itself – the simulation is truer than reality, more pressing, more acute. The subjective experience of the hyperreal world requires an implicit understanding of the evocative, connotative, and affective functions of the phenomena we interact with, and that this implicit understanding is shared by the people around us. In the hyperreal world, images become vernacular and communicative, and self-identity becomes something you perform by publicly and deliberately affiliating with certain images and adopting certain aesthetic signifiers. Performativity – a concept Judith Butler uses to describe gender identity as an “appearance of substance” for a mundane social audience – is the default mode of engagement with the hyperreal world. It is not merely gender that is constructed by images, but all aspects of identity.

If navigating hyperreality means inevitably performing and signalling your identity with your aesthetic and behavioural decisions, it might seem, therefore, that LARP can be explained as synonymous to performativity. This is not the case; the utility of the term LARP is more specific, especially towards describing political phenomena. One might performatively demonstrate their gender identity, wealth status, or political allegiance, but to LARP as any of these things requires an admission that what one LARPs as is not fundamentally connected to their self-identity. Like the knights, jesters, and paupers at the mediaeval fair, these identities stop existing as soon as the LARPer takes off the costume – the eBay-bought camo uniform, the Che Guevara beret, the bespoke AR-15, the Hawaiian shirt. Indeed, this is precisely how LARP is used in the phrase ‘LARP comes after farce’. LARP politics are politics with low stakes buy-in that one can put on like a costume, just to see if it fits. LARP politics are politics which are not fundamentally connected to self-identity because of an underlying belief that they aren’t real and can’t affect change. Furthermore, LARPing, as a phenomenon belonging to Baudrillard’s third order of the image, serves to reinforce the otherwise porous boundary between image and reality. As a mode of engagement in hyperreality, LARPing is a simulation that masks the absence of the real. To declare that something is LARP is to uphold the position that the boundary between image and reality still exists. This provides a helpful clue towards understanding the aesthetics of LARP politics.

Hyperreality describes an ambiguity between image and reality. However, the dialectic between the two still remains culturally understood, and some things are perceived to belong to one camp over the other. I argue that in the hyperreal world of the 21st century, ‘image’ and ‘reality’ have become analogues to ‘online’ and ‘offline’. We have other synonyms that reinforce this dialectic such as ‘virtual reality’, ‘metaverse’, and ‘cyberspace’, compared to ‘IRL’, ‘meatspace’, and ‘physical’. Online phenomena are regarded as belonging to the order of the image by virtue of requiring screens to interact with them. Offline phenomena are regarded as belonging to the order of the real as interactions with them are physical and tactile. Of course, this distinction is artificial; much of the work done by affect theorists over the past thirty years demonstrates how interactions with images can elicit visceral and palpable physiological responses. Additionally, and of course, central to Baudrillard’s notion of hyperreality, our experience of the offline world is also understood via the mediation of images.

Much like the distinction between LARP and reality, the cultural distinction between online and offline is also a function of hyperreality that masks the absence of the real. As described earlier in this piece, the political context of the 21st century is that politics are structured and understood according to their aesthetic features and affective value. For politics to be adopted as, and reduced to, personal style makes sense in the hyperreal world: the political subject is a consumer of images. LARP politics, in addition to describing a political engagement that can be turned on and off like a tap, describes an aesthetic quality of belonging to the internet. Because the online image-world is resolutely understood in opposition to the offline real-world, LARP politics are regarded as bizarre and out of place when they rupture into the real. Like any simulation, though, a rupture into the real is inevitable, and I argue is vital for the emergence of the declaration ‘LARP comes after farce’.

Ruptures into the Real

Baudrillard states that when simulation confronts power, any distinction between simulation and reality becomes useless to distinguish. His analogy of the simulated robbery describes this clash between simulation and reality succinctly:

“Simulate a robbery in a large store: how to persuade security that it is a simulated robbery? There is no ‘objective’ difference: the gestures, the signs are the same as for a real robbery, the signs do not lean to one side or another. To the established order they are always of the order of the real.”

The simulated robbery example precisely demonstrates the tension between hyperreality and reality that I argue is central to our understanding of the absurdity of LARP politics. Like a fourth-wall break, the order of the image intrudes into the order of the real and this tension becomes ruptured. Ruptures from hyperreal simulation into the real are experienced palpably by a society who would otherwise maintain the cognitive distinction between ‘image’ and ‘reality’. These ruptures often become historically or culturally significant events whose consequences vary from grave and traumatic to amusing and idiosyncratic. In each case, these ruptures for most people are disorienting, baffling and hard to understand on their face value. To demonstrate what I mean when I talk about ruptures, I will return to the example of the Capitol Hill riot, where political rhetoric born from the order of images confronts power which can only function in the order of the real.

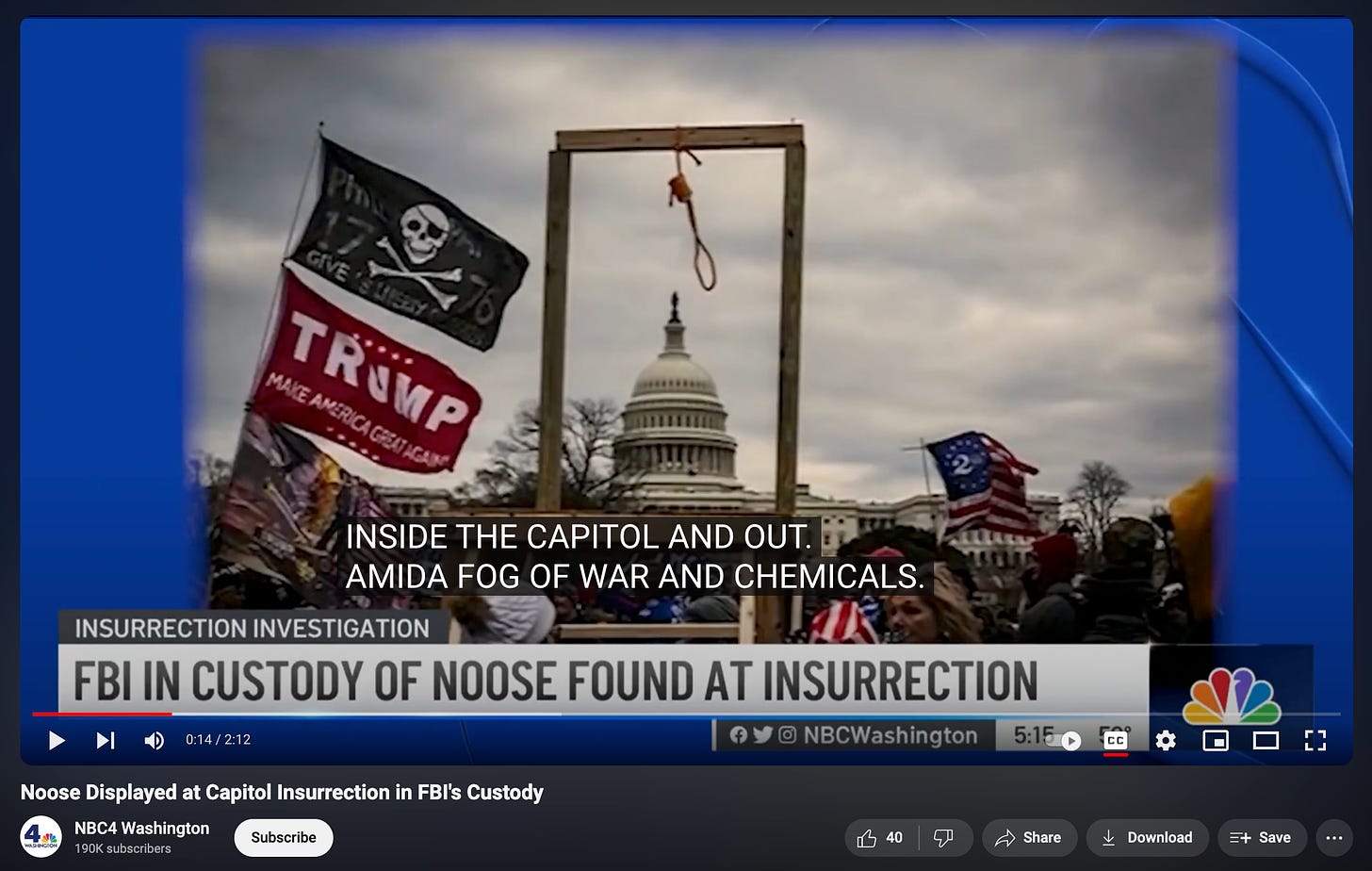

If we consider the Capitol Hill riot within this framework, actions based largely in an ‘alternate reality’ with distinctly online aesthetics were inevitably met with real and grave material consequences: over a hundred people were injured, five people died, property was damaged, arrests were made, and the event became considered a pivotal moment in contemporary American political history. At the same time, the political goals of the riot were unclear (if they existed at all) and the aesthetics found within the riot became infamous for their overall weirdness. The aesthetic weirdness attached to this event is now widely understood; the QAnon Shaman’s appearance, the typically left-wing fist gesture on display by Senator Josh Hawley, the mass of Gadsden flags and Trump 2020 campaign flags, and the gallows paraded towards the building have all become iconic images sitting uncomfortably in the collective psyche of people impacted by US politics.

The gallows specifically provided an uncanny resemblance to Baudrillard’s robbery example and encapsulated much of what LARP politics describes. As an object whose utilitarian function is to hang someone, it was too structurally unsound to fulfill this role. Instead, ostensibly a theatre prop, it served as a metonym for the entire mob of rioters whose actions could only ever replicate a political coup in the realm of the imaginary. Additionally, the ad hoc and onsite construction of the gallows represents a materialisation of the chant to “hang Mike Pence,” a chant which could largely be thrown around online and surprise nobody but becomes treated with much more gravity when it ruptures into the physical world. As such, the confrontation between simulation and power occurs when the construction of the gallows became the cause for a police investigation. If the police were to discover who was responsible for its creation—much like in the example of the simulated robbery—how could any defendant claim that the gallows weren’t in fact real? Messham-Muir and Čvoro also contextualise the Capitol Hill riot as “delegated performance” art, experimentally attributing to Trump himself authorship over the event and to each of the participants the role of performer. For Messham-Muir and Čvoro, it is the performers’ unpredictability and, I might add, ruptures into the real, which provide the aesthetic event an aura of realism. The sense that the Capitol Hill riot can, and ought to, be considered art historically, alongside the attribution to it ‘LARP politics’, serve to reinforce a boundary between image and reality which is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain.

The phrase ‘LARP comes after farce’ has emerged as a compelling addendum to the Marxian adage, describing the sense that 21st century politics is itching for agitation and revolution but is fundamentally incapable of doing so. The impotence of the politics described as ‘LARP’ stems from its location within the order of the image at the expense of genuine conviction and organisation towards material change. The Capitol Hill riot provides an almost perfect case study of LARP politics and hyperreality, but it’s certainly not the only example. As a phenomenon which can be described according to Baudrillard’s notion of simulation, LARP politics inevitably face the real at some point, and their clashes with the real will leave many scratching their heads.

Best characterization of Jan. 6 I’ve seen