Morgane Billuart: Virtuality and Aesthetics, An Evening in the Void Club

I’m gathering in the VR CHAT. I changed the quality of the images and extended it to HD Quality. It does not make anything more realistic, if not only makes the pixel slightly more defined. I observe the symbolic landscape around me. My feet touched the concrete block of yellow sand. The aesthetics are definitely not on point. Through their cubic shapes and pixelated bodies, objects, and people I am encountering are giving me the time and space to nourish my own vision and interpretation of the world I am finding myself in. It is a world where the water isn’t fluid, where the red flag isn’t moving smoothly, and where my face is squared. I am walking in between the dinosaurs, the anime girl, the T-rex, and the butter stick, and no one notices me. From time to time, I say something and guys turn around to tell me “Oh, you’re a female ?” as if I was some kind of rare species on this virtual planet. As soon as this happens, I run away to another room, still wondering what I actually came there for. I enter The Void Club. I am not certain why this place is called the way it is. I am guessing it could be a reference to Gaspar Noe’s movie, Enter the Void, but it could also just be the epicenter of the emptiness of the VR CHAT. I am running (as smoothly as I can) into it. While walking into the club, I sometimes get too close to other avatars and start hearing conversations. I know their voice is real, human, fragile, endlessly echoing in their pixelated bodies. There is not much to do but walk around. No one is really dancing and I could maybe buy virtual drinks but I don’t have any coins. I wonder if the idea of a virtual shot could get me drunk. A group of people is gathering around a wall. I get closer to it and try to observe what they’re seeing. In front of me, there’s a mirror. It’s not a mirror, but I can guess that it is, as it reflects what I am supposedly being right now. In this reflection, I see myself and others observing their digital bodies. Everyone seems confused but fascinated by the phenomena and I can’t help but wonder, if I am observing the avatar I am in, or if it’s my avatar who’s observing me.

1977. Early digital times. A few students from MIT developed Zork, a video game only based on textual experiences without visual stimulation and imagery. One of the aims of this project was to demonstrate how stimulating a world without an image could be. “Zork is all text—that means no graphics. None are needed. The authors have not skimped on the vividly detailed descriptions of each location; descriptions to which not even Atari graphics could do complete justice. ”[1]—David P. Stone in Computer Gaming World, Mar-Apr 1983. A textual experience of an alternative and interactive world reminds us that even in the beginning of computer games and the arrival of internet graphics, one way to ask a player to figure out his own world was to let him draw it with his mental imagery and fantasmia. More than a book to read with a defined narrative, these video games offered the possibility to be interactive and to appeal to subjective visual imagery. These games and platforms demonstrated the possibility that one can have to interpret and project into -almost- nothing, or at least, very little information or guidance. While thinking of the first aesthetics of video games or social online platforms, one could ask if it ever succeeded in the principle of realistic or “ likeness ” of representations and simulations. If not, what was it that could make us so easily fall into the interaction, the belief? Visitors and players knew too well that it is not the reality, or how “alike” one space is, that was at stake, but maybe the idea of it, its interpretation. In these spaces, what is blurred, pixelated, or not represented seems to give more space for the audience’s imagination.

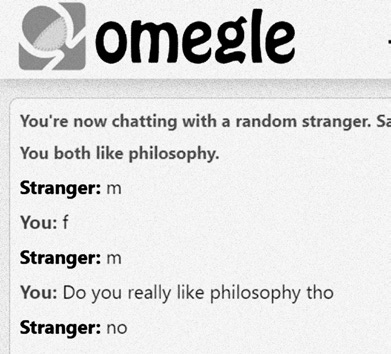

In the absence of things, we may find space for creativity, and speculation. When thinking of aesthetics of anonymity or blinded experiences, the platform Omegle[2], launched in 2009, which offered people to “ talk to strangers ” online, opened a space where one could exist without an image, without a name, and without a voice and still interact with the entire world. If I offered you a ticket to a planet where your gender, race, physical appearance, and body can be forgotten for a moment, would you join me? How can spaces where we are half-blinded give us possibilities of imaginaries and fantasies as well as enhance our feeling of freedom? When traveling in an alternative world, one could suppose that the less there is information, the more there is to be controlled and experienced subjectively and mentally through the mind of the viewer. Sometimes, it seems that ignorance of details helps[3] .

To escape in alternative mind spaces isn’t a brand new practice. Virtuality as a phenomenon is not either. Not so long ago we could run from our realities and routines through books, theaters, games, and many other portals towards the imaginary and alternative worlds. Only quite recently in history came into our environment other digital portals which changed drastically the way we deal with virtuality and which multiplied our ways to escape or distance ourselves from the physical world. This time, these new portals were interactive, interchangeable, subjective lenses, and magnifiers and could travel with us constantly. At first, they offered very simplistic graphics, despicable when compared to our visual expectations nowadays. Still, even today, with higher realistic qualities and rendering options, these virtual portals and devices use the same recipes and principles: the one of keeping the viewer busy constructing their own world by letting him interpret and shape his environment. A certain amount of voids and gaps of information seem to be a great prescription for our minds to project and fantasize upon.

As mentioned earlier, although contemporary digital graphics and experiences are becoming greater and more realistic, certain text-based video games and digital platforms remain successful with this basic principle: the re-creation of narratives and scenery mainly through mental imagery with the use of symbols, text, or visual signs. This isn’t a claim that unrealistic graphics can be more convincing, but rather a way to shed light on how our imagination and projections can be hosted on very basic, still fundamental principles. Before even thinking about what these spaces are made of, one could ask how to first understand the attraction towards this second place, this “almost ”, virtual desire towards something that is close to the initial, but still isn’t. One could ask what we are searching for, in the replica of our world, slightly changed, slightly different, or alternative, rather than to get it from physical experiences themselves. As mentioned earlier; virtuality is a concept that echoes for way longer than the digital era. It’s a space, a moment, a necessity that seems to always refer to a sub, different place or environment where we host desires, fantasies, and sometimes even impossibilities. Although this term -virtuality- seems to have taken the entire sphere of the technological era and its devices, I’d like the reader to think of it as a way to approach experiences, as well as an essential setting that allows imagination and desires to be built.

The success and popularity of this alternative self and alternative worlds, whether ancient or contemporary, physical or mental, invite us to question how and why we can be so easily attracted and convinced by the idea of things and their representation. This attraction for these alternative spaces, these “ third places ”[4] resonate in a semiocapitalist[5] world where we mainly understand, live, and consume through signs, but they also question how much presence and physicality one wants to invoke in their daily experiences. When thinking of virtuality in online and digital spaces, Francesco Casetti, in Sutured Reality, claims that “ the digital image has the ability to offer us a representation of things without ever having need of the things themselves ” and emphasized that these pixelated landscapes owned their own set of aesthetics and symbols[6]. Very much engraved into the philosophy of Jean Baudrillard and his conception of simulations, spectators of these platforms acknowledge that what they see is a reference to what was initially there, or meant to exist, but which somehow remains absent and now can only be echoed by invoking elements, props or symbols. In order for one to project themselves into virtuality it seems not only that we require signs and symbols, but also space and distance.

As William Earle argues that to “distance oneself from the phenomenon is to contemplate it as a phenomenon”[7], I’d like to stipulate that these digital spaces, through the use of devices and the set distance (between the user and the world, the real and the imaginary, the distance which exists in the almost), seems to make this distancing and therefore fascination possible. What I seek when I exist in these spaces, is the absence, impossibility, and therefore desire I can exercise into something that is else, that is almost. When observing objects or actors in a simulated space, whether it is a video game, through social media, or even within our imagination, we experience these phenomena in a distant way, through the lenses of the screen. From our eyes to our minds. This distance is also related to the impossibility (of a situation or a scenario), which enables the desire and fascination[8]. How nice can it be to be able to have this chit-chat on a pixelated moon? How mysterious is it that I could hear the voice, but not to get to know the body? How pleasurable is it to be anonymous? Not only is this experience a recreational one in a distant imagination, but it is also an experience that does not seem to have outcomes in the real world because it seems not to be related to it. When interacting online, or digitally, a feeling of freedom and detachment pretends to set free a lot of our fear and anxiety and offers us opportunities to have adventures, face our fears and live out our fantasies without any physical or financial risk to ourselves. This ideal situation, this optimal world, where one can live, remain and curate without having to deal with consequences and realistic outcomes is one of the structural columns of alternative and virtual spaces as they seem to open doors for things that the physical and external worlds wouldn’t accept or render as possible.

While thinking of alternative life and digital simulations, many fiction and movies come into play. Black Mirror, Matrix, Her, Avatar, and other cinematographic realizations attempted to underline the power and attractions of these spaces. Realistically, one of the moments where we were close to having a normative alternative virtual life in the past decades was when Second Life was launched in 2003. When initiating this virtual society, no one expected the success of this world where virtual trading, virtual marriage as well as virtual rape became real things. Although its graphics and ‘likeness ’ were not amazing at the time, it did not stop users from totally projecting themselves into the role-play of the game and living an alternative, if not, a better life than what the one they were being offered out there, in the physical world.

On Reddit, PabloBecool asked openly: “Why are the graphics so bad in Second Life? ”[9] There, a stranger answered: “ In other virtual worlds, most or all of what you see is generated by a design team employed by the world provider (...) We make our own stories here. The result is that we trade away some performance for the opportunity to peek inside each other’s brains. Whether that’s a good or a bad thing is up to you. ” This quote from the SecondLife forum opens up the discussion of the mental activity in these processes as well as the act of trading minds’ experiences. More fundamentally, the worldwide success of these platforms and other everlasting virtual communities with very unrealistic or minimalistic aesthetics leads us to rethink and consider what is needed in order to believe in a situation, an image, or an idea and to feel fulfilled or immersed. In the research “Semiotics of virtual reality as a communication process ” B. R. Barricelli, D. Gadia, A. Rizzi & D. L. R. Marini searched and studied different scales of symbolisms in digital spaces and emphasized how much of the role of the viewer as a “builder of the necessary encyclopedia by getting the knowledge of the virtual world from his /her personal knowledge and previous experience or through progressive exploration of the virtual world. ”[10]

This research emphasizes how much of the subjectivity of the viewer comes into play when understanding these spaces, and how much they have to interpret and connect the signs for themselves. In 1979, when Umberto Eco published The Role of the Reader, he tried to demonstrate the capacities and needs of one’s reader to get the key to reading books. He emphasized how much the reader shapes the understanding of the book, leading it to a multiplicity of interpretations. In the same way, as when one reads a book and projects themselves through its symbols and metaphors, digital and virtual spaces seem to also have their own set of symbols and rules for the user to dive into, while also unfolding as the user travels within it. Nonetheless, this time, something is radically different: the reader is now a user, and the user has a multiplicity of tools to shape their environments. In the same study, Volli proposed four kinds of possible worlds: “verisimil that can be easily conceived and could correspond to some real world, non-verisimil when a suspension of disbelief is needed, non-conceivable when some logical rule is broken (think, for instance, of Alice in Wonderland by L. Carrol). ” It is then noticed that we seem to be able to accept certain situations not to be real, or “alike” to happen when being in a virtual situation. The idea of suspension of disbelief when finding an element or situation that is not “alike ” in these worlds and experiences seem to appear as a pact in between the simulated world and the user as to say “ I know it is not possible, but I will believe that it is for the sake of the experience.”

Needless to say that the promises that we used to make with virtuality when we would turn our computer on and off are very much presently a blurred limit in our digital era where we always remain online thanks to our devices and digital personas. Where do we draw now the lines of our disbelief in these spaces? Whether it is in a textual or visual realm, virtual places have their own set of rules for subjective interpretations. When combined together, the visual lacks and word allusions offer spaces where imagination and fabulation can flourish and grow and where our minds travel freely. In these digital landscapes, we seem to be more than able to create new ways of seeing and understanding based on what is given to us, just as machines. When a software or algorithm uses interpolation, it is understood as such the addition of a number or item into the middle of a series, calculated based on the numbers or items before and after it; a number or item added or the addition of something different in the middle of a text, piece of music, etc. or the thing that is added. Borrowing the term “ interpolation” when thinking about assimilations of ideas and scenarios while being in a virtual space might be a way to understand how we can project things based on the absence of knowledge or information. In their research “On the Role of Metaphor in Creative Cognition”, Bipin Indurkhya stipulates that “all conceptualization involves some loss of information, and that some of this lost information may be recovered by projecting a different gestalt or a different set of operations onto it. By inviting us to see one object as another, we are forced to project the conceptual organization of the second object (usually referred to as the source) onto the experiences, images, etc. of the first object (usually referred to as the target)”.[11] They conclude on “an account of cognition here in which cognition necessarily involves loss of some information. Creativity essentially lies in recovering some of this lost information, and metaphor plays a fundamental role in this process.”

Metaphorically, the virtual becomes this line with gaps within, where our minds try to fill voids and start building new information and interpretations. In this regard, I’d like to formulate that like machines, humans in digital spaces practice their own form of interpolation. Nevertheless, this hyper-subjective narrative we create for ourselves while filling these voids doesn’t make us necessarily more content, if anything, more delusional. As Geert Lovink mentioned it in his book Sad by Design, our relation to these spaces is defined by “ scrolling, swiping and flipping, we hungry ghosts try to fill the existential emptiness, frantically searching for a determining sign—and failing”.

Although this entire speculative and subjective universe demonstrates our needs and capacities to project and fantasizes from -almost nothing, how can we question these practices by underlying the danger of overly curated experiences? By generating a world of symbolism and imaginary settings where players or users are mind-enhanced, how do virtual and digital spaces invite us to shape and create our own stories and narratives? It seems like we’re now more than ever able to be, not only the actor, but the director, the scenarist, and the editor of our own lives, and that existence might not be as much of an experience anymore, but rather a designing and curating problem.

I was rather confused when I heard about the launch of Meta in 2020, in the midst of the pandemic. To propose such a poorly rendered environment, additionally with the use of VR glasses while we were all stuck at home glasses sounded like torture. Simultaneously, one has to understand that an online social media as big as Meta which would run with Unreal Engine Aesthetics, would be, to say the least, heavy. Also, if Unreal Engine’s aesthetic challenges the contemporary ways to think of creating images and films, realism and perfectionism of details aren’t the only requirements for a great virtual experience. Often, the most important details dealing with timeframe, the reactivity of other characters, and sound come at a more expensive price than visuals. Has anyone heard of that saying? “You can make a great movie with great sound and bad images, but you can’t make a movie with bad sound.” Similar dynamics apply to virtual environments.

In Digital Imperfections: Analog Processes in 21st Century Cinema, Christopher Blake Evernden writes about the different processes to imitate art and life through digital processes: “Both absence and imperfection are essential to selling the illusions of the cinematic landscape”, “The pursuit of perfection results in perceptual alienation for the audience because the spectator is put into a “perpetual state of perceptual crisis” (...) The imperfect nature draws the viewer closer to fill in the details and appreciates the craftsmanship behind the illusion, rather than pushing them away with the perfectionist digital rendering that does not require their presence.” By reinviting a virtual world that some would love to claim “a replica of the real”, we need to question again the criteria of relationship with reality, and our boundaries when creating new ones.

[1] Mart Barton, “The history of Zork”, Gamasutra, June 27, 2009

[2] “Talk to Strangers! ” Omegle. www.omegle.com

[3] Willem Fussler, Into immaterial Culture, Metaflux Publishing, 2015

[4] Ewa Markiewicz, “Third Places in the Era of Virtual Communities”, Poznan University of Economics, March 2020

[5] Francesco Berardi, And: Phenomenology of the End, Semiotext(e), 2015

[6] Francesco Casetti, “Sutured Reality: Film, from Photographic to Digital. ” October 138 (Fall 2011)

[7] William Earle. “Phenomenology and the Surrealism of Movies.” Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism 38, 1980

[8] Kluitenberg Erik, Delusive Spaces: Essays on Culture, Media and Technology, Institute of Network Cultures, Rotterdam 2008

[9] PabloBeCool, “Why Are the Graphics so Bad? Why Is There Lag Time?” Second Life Community,

March 22, 2016

[10] B. R. Barricelli, D. Gadia, A. Rizzi & D. L. R. Marini, “Semiotics of virtual reality as a communication

process ”, Behaviour & Information Technology, 2016

[11] Indurkhya, Bipin “On the Role of Metaphor in Creative Cognition”, Cognitive Science Laboratory