Jak Ritger & Anthony Simons: Plotting Attention Bubbles

The attention of the socially minded internet user is if nothing else: fickle. Crises, calls to action and outrages rise in relevance and engagement at breakneck speeds, and are forgotten equally fast. Though critiques of an overreliance on identity politics, exploitative algorithms and corporate bearhugging offer interesting perspectives- the phenomenon of the attention bubble seems to span categories that stretch these explanations too far. After a year whose online fingerprint is the carousel instagram infographic (How you can help), many of us are asking what all this attention really bought us. Did we save the post office? Am I really the best antiracist I can be? Here we explore what makes an attention bubble, and how we might keep them inflated. We aim not to offer another tired bemoaning of the sorry state of the online left, but to start to imagine a left-future where single issue advocacy groups collaborate with one another to plant seeds that grow offline. One where, even as peak engagement online fades, enough are converted into real world action that the movement is not doomed to long forgotten Instagram stories.

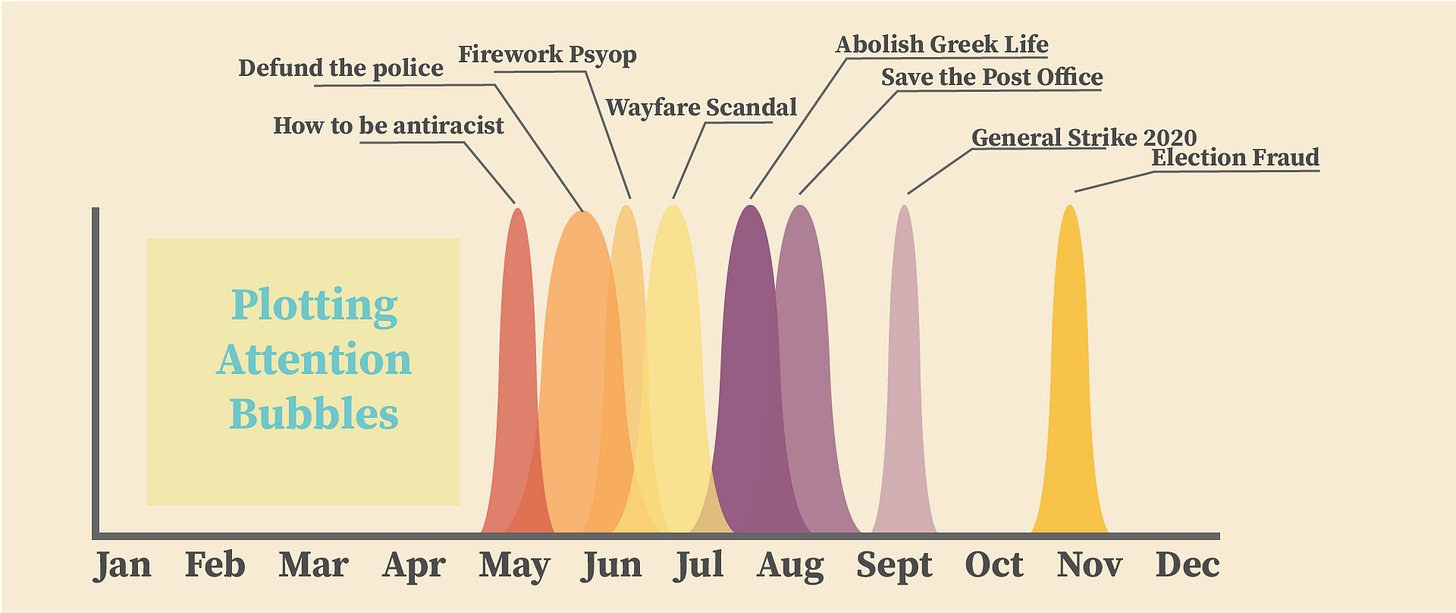

The subject matter of attention bubbles vary greatly. As illustrated in the graphic above, they can range from calls to mass action of the working class, to theories that law enforcement are utilizing fireworks as psychological warfare, or even Q-anon seeded conspiracy theories. What they have in common is their ephemerality. The content of the above plot represents the simplified Google Trends search data for the displayed term over time. In many such cases, the topic reaches its maximum and crashes back to barely detectable levels within as little as two weeks. Rarely will they sustain even 25% of peak activity for more than a month. Like the street action folk politics that define the most visible left agitation today, the 5-slide infographic is immediate, shareable and bite-sized. Presentism dominates the discourse. But do they work? Where does this tendency come from?

In 2012 a non-profit charity organization called Invisible Children launched a campaign called #KONY2012. The group had been building steam for a couple years in the missionary trip sector by creating activism events and fundraising drives around the issue of child soldiers in Africa. The mission reached it’s apex when a short-form Vimeo documentary went viral on Facebook. The film followed the personal journey of Invisible Children’s founder as he discovered the plight of child soldiers and resolved to do something about it. The video was followed by a clear call to action: share on social media, inform your network and donate. As the viral hit snowballed into a full fledged media moment, the donations flooded in. But, so did the reporters. Journalists uncovered lavish expenses on the Invisible Children tax disclosures (ostensibly to woo donors) as well as analysis of how the organization was effecting change on the ground in the Democratic Republic of Congo. They revealed that the aid money was not going to those in need, or worse, was creating more instability among warring guerrilla factions. It became even more complicated when the target of #KONY2012, Warlord Joseph Kony, was revealed to have been supported in the past by foreign political interests. After one week of incredible media attention, Invisible Children’s founder suffered a mental breakdown and was caught running through Beverly Hills naked by paparazzi. At the end of the saga we are left with an intractable weariness that Adam Curtis described in a film of the same name as “Oh Dearism.”

The dramatic rise and fall of #KONY2012 laid the foundation for a model of activism and business that in the following ten years has become familiar: Single-issue campaign supported by a network of non-profits, complex political issues reduced down to essentials, awareness spreading media, call-to actions, donations, attention economy spirals, and rapid drop-offs after the moment has passed.

Slacktivism is an old term that would be easy to apply to this phenomenon. It is largely inappropriate however, because despite the online-focus, attention bubbles today seem to be doing something different- inspiring more financial support and real life engagement. Bail funds and mutual aid networks raised millions of dollars in the summer of 2020 as the United States boiled following the murder of George Floyd. People being too lazy is not the issue. But still, over a year later, Minneapolis hasn’t shrunk its police force by a single officer, and its budget has been cut by a laughably small amount. At the time of writing this, at least 3 more high profile killings of black men have occured in the Twin Cities metro area since. And while a dedicated core of IRL organizers continue to agitate for defunding, the wider social presence of the discussion disappears. As an organizer shouted at a street protest after the killing of Winston Smith, “where the fuck is everybody now?”. Something new is being shared now.

The only thing that can crush the anxiety of disparate types of pain calling out across social media and perhaps get some real results is a universalist coalition of working people in solidaristic collaboration. With all the slow motion horror of 2020, still the most salient feature was the endless chain of panics and crises shown in images across screens. Every single one deserves your full attention. How could one possibly choose? Do you Venmo five dollars to all of them, go to each protest once? Or do you stay home and let each one wash over you- a little more ashamed and cynical with each tragedy retweeted? The description of these things as “single issues” is itself misleading. What is being witnessed is a symptomatic cluster resulting from a nested and reciprocally reinforcing structure of capitalism, racism, patriarchy and imperialism. Therefore our struggles, both for attention and power, must be likewise nested and reciprocal. That is to say, despite one person's foregrounded commitment to ending the drug war and another’s to organizing service workers, both must be as mutually reinforcing and integrated as the poisonous regimes they seek to abolish. Practically, this may mean that you don’t need to find the most radical organization before you take your work offline, rather, you must take your radical imagination to the organizations already on the streets.

Glimmers of the future of internet organizing are visible today, while others are yet to be imagined. Yancey Strickler’s “Dark Forest Theory of the Internet” gives name to a growing phenomenon where netizens emigrate from the mainstream platforms to smaller, less gamified ones, where the potential for ideas to incubate is arguably greater. The term “cozy web” is a name for a subset of these spaces that are gatekept and private, coined by Venkatesh Rao. These alternative gathering places allow a more sustainable tempo that might be less prone to the attention bubble cycle. Most fundamentally, the question of conversion rate must be addressed. For every person who sees a call to action, how many donate, attend or even seek more information? Who likes the post and moves on, and who integrates it into their embodied political life? There are a variety of hypothesized forces that push people further down political “pipelines”, and many of them are already effectively utilized by the political enemies of the left. Youtuber Faraday Speaks described a dark incarnation of this process in his video “My Descent into the Alt-Right Pipeline”, where extreme right wing influencers capitalized on algorithmic exploits, isolated young people and appeals to “community” to steer a politically naive Faraday into increasingly radical right wing spaces.

Whatever forms it may take, the next evolution of online politics will need to step off of the take-treadmill or be resigned to content milling for the major social platforms to extract profits. The liberatory World Wide Web dreamt up by the cyberpunk libertarians of the 90s has not come to pass, and we are on track for further consolidation by a handful of platforms. While calls to simply “log off” are memetically seductive and touch on the real need for physical facetime with like minded people, it would be a mistake to leave this infrastructure in its current state. We also cannot simply interact with the platforms on the terms of their internal logic laid out by a smattering of Silicon Valley founders. In the prescient words of Prince: “It’s cool to use the computer, don’t let the computer use you”.