Excerpt from Exposed Nerves and Archival Impulses

Isabella Haid

Those of us who grew up online can easily recall the refrain: “once you put something on the Internet, you can’t take it back.” But reality suggests otherwise: this fear tactic failed to account for the digital ruins which we encounter daily. They are so familiar, in fact, that we have become immune to the threat of loss. Irritated by the pop-up warning of a broken webpage or disheartened by the words “This Tweet has been deleted,” we have outlived the fanciful delusion of digital permanence. We collectively witnessed the quiet disappearance of GeoCities, Vine, Microsoft Explorer, Adobe Flash, and countless other platforms. All of which we commemorate through video compilations, memes of mourning, or open source emulator projects. And in overcoming this fear of an Internet that does not forget, a new kind of relationship to the Internet has emerged: when we log online, we willfully situate ourselves inside of a ruinous landscape. We are accustomed to the horror of nothing to be seen: navigating broken webpages or abandoned servers has become a coming of age ritual. We find ourselves unable to “take back” what we say or do from the Internet’s memory not because it became a facet of forever, but because it was displaced, sold, overwritten, or in some way ruined. We are acutely aware of the uncertainty undergirding digital media and its infrastructure. Similar to Hito Steyerl’s poor image, which “mocks the promises of digital technology... Only digital technology could produce such a dilapidated image in the first place.” While we expect computers to just work, the nature of our interactions with the machine shows that we still instinctively approach it aware of its imperfections. Twisted by a culture of obsolescence and seized by the fragmentation of the Internet, networked activity is a confrontation with ruin.

Neoliberal networked time, Robert Hassan’s term which denotes the global logic of computer network driven speeds, provides the basis for digital ruins which I describe as dust and debris. It also serves as a polyvalent signifier for the many senses of time that digital media produces, and that we, as avatars, play through.1 Predicting the trajectory of information technology, Paul Virilio thought up a “never-seen-before accident”—a total surprise, a dizzying deluge of unintended consequences resulting from accelerated time.2 I argue that Internet memes constitute this “never-seen-before accident” he anticipated, accidents which cause decimation and regeneration in a series of cascading temporal collisions.

Memes are the rubble of the ruined digital landscape. That is to say, they are raw, chaotic material that can be mobilized to create new forms and meanings. As theorized by anthropologist Gaston Gordillo, rubble has form and can be reformed, repurposed, or resourced. Unlike conventional theories of ruin, which speak of picturesque collapse and show little interest in the mess which remains, rubble-ruin seeks to destabilize this “hierarchy of debris” in regard to digital ruins.3 In turn, the memetic life cycle has no stable point of origin, author, or context. The dust and debris which litter the Internet—outdated OOTDs, recorded live streams, deleted tweets or clickbait banners gone unclicked—are the raw material for memes. At the peak of their popularity and after we’ve all stopped laughing, memes, too, are like rubble. I say dust and debris to denote the observer’s effect on memes: like particles being observed, the human agent necessarily changes the matter itself. This is also to say that they do not arrest agency, but are part of the assemblage of nonhuman components across which agency is distributed in the making of a digital avatar. Like us, from dust they are made and to dust they will once return. Going forward, I want to understand the enduring quality of digital ephemera by assessing the myriad lives they can live, die, or be reborn.

Exploring rubble as “textured, affectively charged matter” prompts us to wonder, what do memes make real? Turning back to Gordillo for a moment, he explains that the hypothetical ruin represents the deliberate attempt “to conjure away the void of rubble and the resulting vertigo that it generates.”4 Memes are also tools for crafting collective identities as we seek to resolve our splintered subjectivities and recover from a state of disorientation. They conjure subversive arrangements of people and taste through re/producing aesthetic sensibilities, ironic detachments, and an anti-corporate ethos. Memetic content also allows us to read the audience: could this be more than mutually assured destruction? We confront ruins by playing with and through them: memes are musings on accelerated time. Two horses are running on the track, neck-in-neck. Memes are the only cultural ephemera capable of keeping up with neoliberal networked time.

The infrastructure of the Internet appoints the meme as a multiplier, control switch, and storyteller—a masterful design of desire. Memes ecstatically surrender control to both vectoral powers (the owners of the platform, its data, and its algorithms) and their adversaries (the taste and curiosity of the user, and the whims of fandom). Users negotiate fluctuating dynamics of their own networked subjectivity through memes. Vectoral formations guide innovation, obsolescence, and moralistic model-making by means of religious adherence to Moore’s law, routine capture of data on platforms, and enforcement of neoliberal networked time. The computational power of vectoralists like Apple, Meta, or Microsoft has the ability to problematize concepts of user agency by aligning creative labor with a market-driven logic. But user agency is not totally compromised, given that avatars are uniquely positioned to critically un/play these games of algorithmic domination

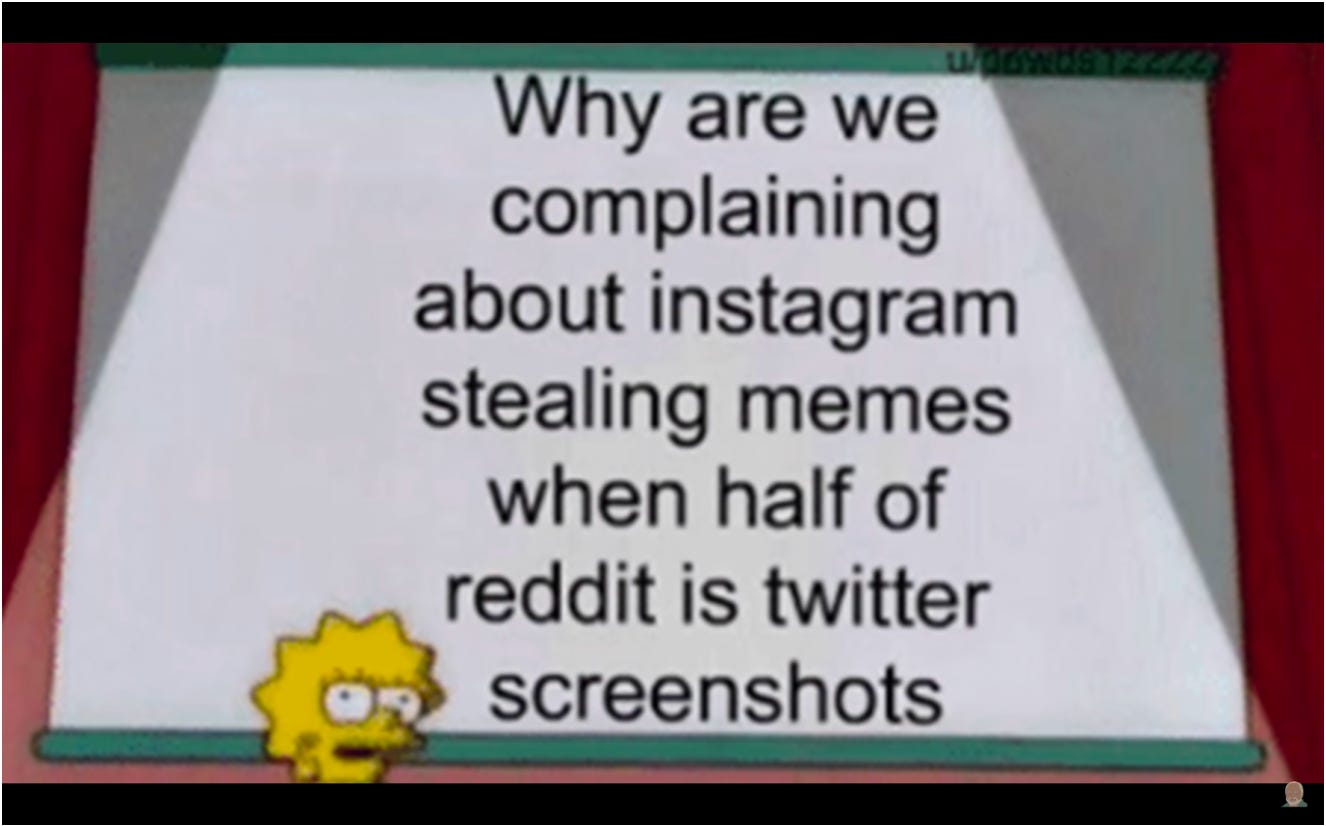

Memes are dismissed as objects of critical inquiry for various reasons—too ugly, too niche, too cringe, too ephemeral—but as rubble-ruins, they become the vital refiguration of digital ruins, the undead media capable of penetrating the platform’s garden walls and producing a networked landscape in their image. Platform collapse is not possible without memes. Platform collapse is a reality made possible by memes. Platform collapse is a process driven by memes. Platform collapse is a top-down process in the sense that all apps are converging on the same media forms (incorporation of video, the story, live streaming capabilities, or FYPs to filter content), and their ownership is being rapidly concentrated into a handful of companies. If we read this collapse through the lens of the avatar and its playful antics, this collapse has been a crux of the online culture war for the past decade. Think of an Instagram reel of a screen-recorded TikTok of a slideshow of screen-shotted 4chan greentexts. Or a twenty-minute YouTube video of a series of Reddit posts being narrated with the original thread scrolling down the screen. Platform collapse is a meme in and of itself. Memes weave through intricate legal loopholes and community content guidelines, unifying the experience of being online. Even with an ostensibly fragmented Internet, memes are as ubiquitous as the Internet itself.5 As a goal, platform collapse can be measured by the rules and regulations set by vectoral powers in a game of media domination. As a process, the speed of platform collapse sets up a messier game, one in which rules are not obeyed, but mercilessly toyed with.

I propose that memes evince the regenerative capacity of digital ruins in their potential to be re/made, re/purposed, and resurrected. By nature of the rubble-ruin, memes are imbued with the dual powers of remembering and forgetting. Vessels for dislocated memories, memes rewrite the typical narrative of ruination from pessimism to optimism and back to pessimism. We pessimistically assume that the worst will happen— that everything will disappear— and link this with the belief that good can come of it, that more pathways to different futures will unfold only when we are willing to let the dead mingle with the living. But this hopeful pessimism of sorts is followed by a fear, or certainty that the worst will happen again. And so this fear is replaced by an acceptance of the ruined landscape, inviting critical play and a perspective on remembering as a deliberate and fugitive act.

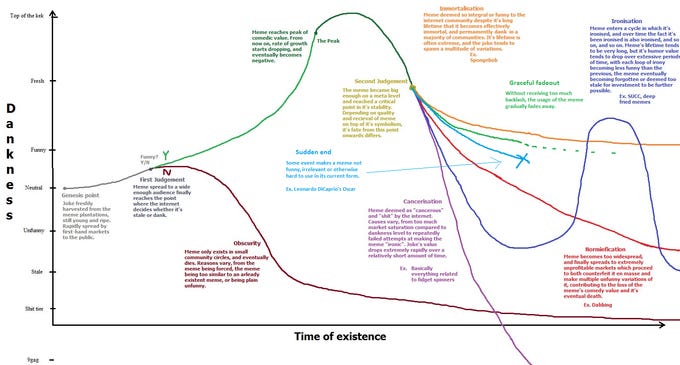

We can measure, not in weight but in trajectory, the regenerative capacity of digital ruins by analyzing user interpretations of the memetic life cycle. While my personal model faithfully follows remember, man, you are dust and unto dust you shall return, many Internet users have constructed their own formulas, timelines, and diagrams to work out their observations and feelings. As I compare and contrast their conceptualizations, I do not aim to prove a unified theory of meme death; rather, I hope to demonstrate that users engage in ongoing negotiations of digital ruination. Users are not passively consenting to the terms of acceleration, so we should not limit our curiosity to the content itself. As Wendy Chun maintains: “we must analyze, as we try to grasp a present that is always degenerating, the ways in which ephemerality is made to endure. What is surprising is not that digital media fades but rather that it stays at all.”6 I present three approaches user’s have formulated to interrogate this surprise specifically at the level of circulation: linear, cyclical, and rhizomatic.

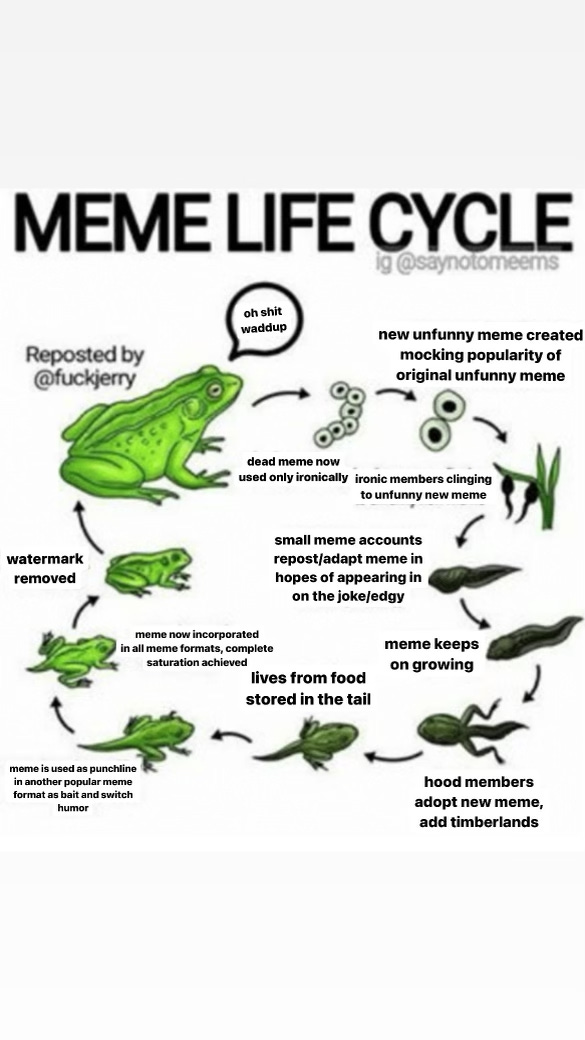

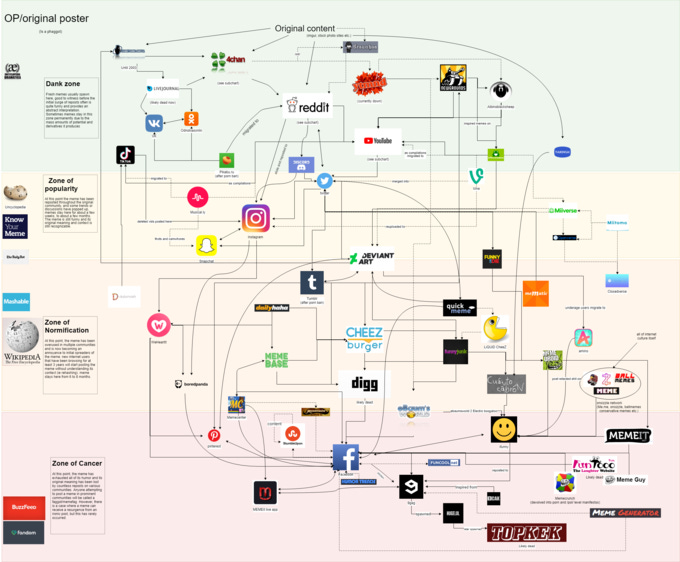

The linear model plots memes along a Dankness vs Time axis. After the “neutral” birth of the meme, the first turning point it meets decides its fate: will it tunnel into the vortex of esoteric memes, or climb the content ladder and reach a mass audience? It recognizes the possibility of meme death as that which either fails to reach a wide audience (“obscurity” path) or garners an audience far too wide (“normiefication” path). The meme also has a distinct “genesis point” that is marked “neutral”, implying that its source can be known and that it lacks inherent value. Value must be made through the process of circulation—which I argue is a process of ruination. This attitude demonstrates that the circulation of a meme imbues it with meaning, and that the secret to transcending death is “spawn(ing) a multitude of variations” like memes which undergo “immortalisation” or “ironisation” tend to do. “Ironisation” is further investigated by the frog-themed life cycle, which operates on the same assumption that there is an hierarchy of platforms. Assigning value-judgments to platforms according to their user base, and assumptions about how these users might identify, implicates notions of identity, authenticity, and kinship. What the cyclical model believes, and is somewhat occluded in the linear version, is that the memes are made from other memes: the point of origin is thus destabilized so that the un/dead rise again. Together, the linear and cyclical models describe a process of meme-ing that is hyper-aware of the network ecology, but only to the extent that memes are valued based on an in-group, out-group dynamic. While some meme scholars have argued that this power relation is the core of a meme, I believe this view fails to account for alternative conceptions of meme circulation that inform critical meme-making.

The rhizomatic model, too, grades platforms on the basis of authenticity (memes originate in the “Dank zone”), but undoes the hierarchy with multidirectional flows. It combines features of the linear and cyclical models to imagine a life cycle of memes that is contingent, decentralized, and nonlinear. Digital ruination is thus figured as a sort of entropic death, the circulation of memes following outward and inward trajectories which “oscillate ambiguously between instance and plurality.”7 Neoliberal networked time lingers in the interstices between each of the zones, gracefully sliding content from “normification” to “cancer” and back into the “dank” zone in less than a 24 hour time frame. In Circulation and its Discontents, McKenzie and Scott Wark explain that information technology “fragments individual subjects into dividual components, weaving each into the information production process to the point where it would no longer be possible to distinguish living from dead labor.”8 I bring this up to address the coexistence of not only machine and human labor in the circulation of content, but of dead and living labor. The rubble possesses value not because of its use-value but for its exchange-value, a fixture of the meme economy which has the potential to disrupt or boost the value-generation of a meme.

In all of these examples, critical meme-making is a means for users to inspect the rubble-ruin, make friends, enemies, and make believe. The cosmologies of meme magic—and their constructions of center, peripheral, and liminal space—depicted in these models reflect new rhythms of movement which are discernible, if not frightening. Embodying repetition and endless referentiality, the meme encapsulates an out-of-scale experience of media’s “planetary distribution.”9 Networked activity thus moves beyond a confrontation of ruin, and is an ongoing negotiation of the ruin’s aesthetics, politics, and critical capacity.

I would like to note that these three examples are sourced from Knowyourmeme, the implications of which are as follows. The only source information cataloged with these submissions is the time it was uploaded to the database. No information about the original date of creation, when or where the uploader first encountered it, or even the tools used to create it are provided. Perhaps this information is irrelevant, as we will see, given that there is hardly ever a clear point of origin for memes (who made it or why it was made are questions which often escape the meme archaeologist) and their meaning is largely derived from the piling of plateaus. In the words of Hito Steyerl, “living and dead material increasingly integrated with cloud performance, slowly turning the world into a multilayered motherboard.”10 To read a meme, you must read underneath, inside, and through it. This is a core issue for meme preservation: even if we can deconstruct its composite parts visually (we know how to distinguish font styles and celebrity faces, for instance), many data points necessary for complete comprehension remain unknown. Memes are always in the process of becoming. Platform collapse, too, complicates any reading of memes or their life cycles. Archiving memes in a manner such as Know Your Meme is an act of contextualization, stabilizing their narratives and choosing an interpretation— an act which runs up against their whimsical and dynamic nature. This effort arguably works toward fixing the meme’s meaning, and thus limiting its possibilities of re/mixing to more logical conclusions.

On the other hand, a meme archive— be it a personal collection on your phone or public collection like Knowyourmeme—does not strive for totality, but un/plays it. Archival impulses as a consequence of Cycles of Dust and Debris do not obsess over granular detail. In fact, most public meme collections are actually very alive. Though they do tend to settle for an explanation, they continually update old data to meet evolving trends in and uses of memes. The meme, like the avatar, is not a quantifiable or predictable object, but a vessel for experimentation that mediates our networked subjectivity. The shortcomings of the meme archive, then, might actually open a new vision of the archive altogether, one that accounts for archival impulses and honors the localized networks of knowledge that emerge.

What is almost always obscured in these theories about Cycles of Dust and Debris is labor. Not prosumership, not the free labor of content creation or affective labor of dressing the wounds where nerves were exposed, but the tedious and taxing labor of content moderation. Its results hypervisible and its workers fully invisible, content moderation has been described as ghostwork.11 Content moderation has high stakes—i.e., working to make sure that I was the last group of kids who could stumble upon beheading videos in between playing Flash games and reading fan fiction—to establish some standard of safety and harm-reduction in networked spaces. Under neoliberal networked time, the content moderator is a human forced into cyborgdom—not through a synergy with the machine, but a demand to be machine-like (objective, detached, unemotional, and unafraid) when being tasked with cleaning the filth from the Internet’s sticky servers. Neoliberal globalization has pressured us to work faster in all industries, sectors, and nations, and promised little more than precarity as a result. But I draw attention to the content moderators specifically to say that for all the talk of meme magic (mycelial networks and algorithmic domination), there is actually a very human component that re/directs the rubble and its creative capacity. We might bend down to pick up the rubble and feel inspired, feel a sense of wonder staring at the microcosmic ruin. Following through with that gesture, I suggest we slow down, look up, and hold on for just a second longer before making any decisions. Critical meme-making plays with the pressures and limits of our accelerated culture at the levels of content and form; however, it cannot help but reify the asymmetry of power by giving the vectoral class more stuff to own, more data to mine and refine their algorithms. Maybe Virilio’s predicted “never-before-seen accident” to occur in the age of acceleration is actually the result of what happens if we all slowed down.

Content moderation and meme-making are both comparable to spiderwork in the sense that they involve a constant process of untangling an intricate web of information, be it for the purposes of self expression or a paycheck. As making meaning from the rubble-ruin is a similar process of coming through the dust and debris online, maybe this process of ruination could help us imagine an alternative model to content moderation that relies on networks of kinship and care, and not the payroll of vectoral powers. At the very least, this model of digital ruination reveals that the avatar’s agency is not simply subdued by vectoral formations, but actually a potential source of creative resistance in networked space.

1 I prefer the term avatar to user when talking about networked subjectivity because it understands online spaces as game worlds and centers the user’s agency.

2 Virilio, "Speed and Information.”

3 Gordillo, Rubble: The Afterlife, 10.

4 Ibid.

5 *I speak from an American context, and so my views are in turn limited by the borders erected by and between networked devices.

6 Chun, "The Enduring," 171.

7 Wark and Wark, "Circulation and Its Discontents," 303.

8 Ibid., 297.

9 Ibid., 301.

10 Steyerl, "Too Much.”

11 Gray and Suri, Ghost Work.

References

Chun, Wendy. "The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future Is a Memory." Critical Inquiry 35, no. 1 (Fall 2008): 148-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/595632.

Gordillo, Gastón R. Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014. PDF.

Gray, Mary, and Siddharth Suri. Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass, HarperCollins, 2019. PDF.

Steyerl, Hito. "Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?" E-flux Journal: The Internet Does Not Exist, April 2015, 10-26.

Wark, McKenzie, and Scott Wark. "Circulation and Its Discontents." In Post Memes: Seizing the Memes of Production,, edited by Alfie Brown and Dan Bristow, 293-318. N.p.: Punctum Books, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11hptdx.

Hassan, Robert. "Time, Neoliberal Power, and the Advent of Marx's 'Common Ruin' Thesis." Alternatives 37, no. 4 (November 2012): 287-347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0304375412464134.

Virilio, Paul. "Speed and Information: Cyberspace Alarm!" In CTheory. Last modified August 27, 1995. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/ctheory/article/view/14657/5523.

Excerpt from Exposed Nerves and Archival Impulses: read the full piece here.

Fuckjerry is basically Ellen for the memesphere

this made me cry like a big fat baby