Enduring AI Power Structures: Nuance and System Fragility

The amount of talk that coddles and bestows god-like status upon AI from the likes of techno-evangelists like Peter Thiel and his eerie cult of "technologists united in the mission of building a new city on the Mediterranean" (aka "Praxis"), often coaxes me to toss my computer out the window—a sentiment I am sure many of us share. It has, however, gotten me thinking about how the collective perception that is being built of what AI represents depends so much on language. Language not only trains these programs, but anthropomorphic and fictional metaphors add confusion to a difficult conversation that is dominated by Silicon Valley, despite efforts on behalf of researchers, theorists, and artists to counter their loud and expensive jargon. An array of state-of-the-art programs equipped with artificial intelligence have rapidly surfaced within only a couple of years. This unprecedented defrosting from a comparatively long “AI winter” was largely made possible due to the fact that these new programs could be based on language—English, mostly, used to describe Western values in training sets.

In his essay Crapularity Hermeneutics, cultural theorist Florian Cramer sees the interpretation of language as the blind spot of data analytics. He compares the latter to the gibberish interpreted by priests through exegesis and highlights the importance of hierarchy: the programmer or tech CEO, like the priest, sits comfortably at the top and establishes the rules that determine any future representations. Data is delivered as quantitative, statistical, self-evident, value neutral, when in reality it is truly "always" qualitative and co-dependently constituted, he argues. In 2018, he worried that through techno-capitalist implementations of smart cities and social scores, we have already crossed the threshold of what he refers to as the crapularity—his riff on the singularity, a term for an AI takeover that tech giants love to distract us with.

"People worry that computers will get too smart and take over the world, but the real problem is that they’re too stupid and they’ve already taken over the world." It may come as a surprise that these words from Pedro Domingos’ book, The Master Algorithm, were made in 2015–already ages ago on the AI timeline–because today, they couldn’t resonate more. It is naive to believe that the goals of tech firms are limited to creating generative playgrounds for our entertainment, or selling image processing techniques, or wanting to place the internet in all-the-things so that cities can become as "smart" and “efficient” as possible.

How fragile are these spectacular programs, though, and who are they really serving? Current capabilities in training neural networks are streamlined for Western and capitalist demands—profit, consumption, production, speed, efficiency, perfection. How else, outside of what we are being administered by tech giants, the media, and the West, could they be opened up and used? What stories are at risk of being lost? How might cultural erasure be perpetuated by these technologies?

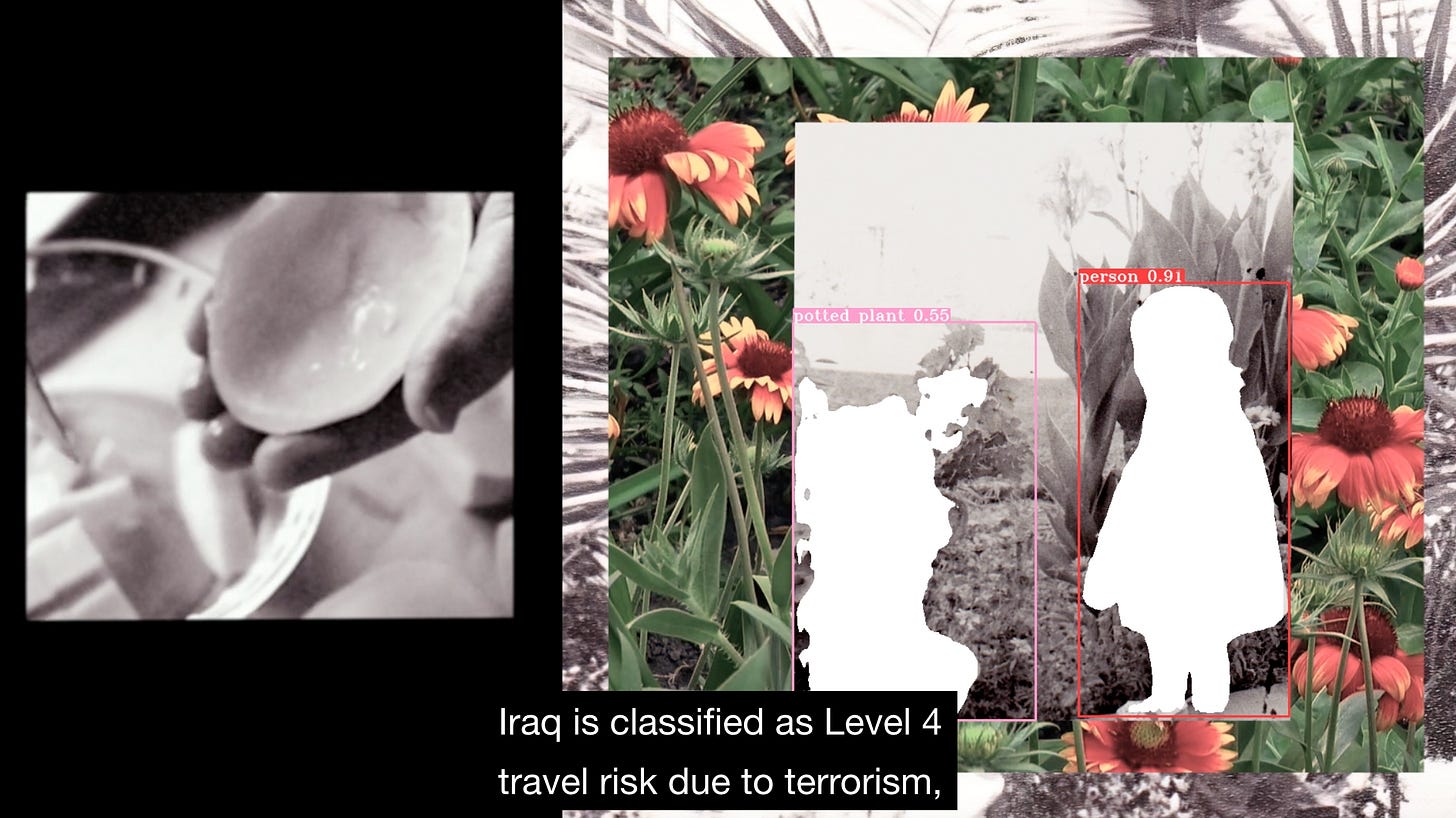

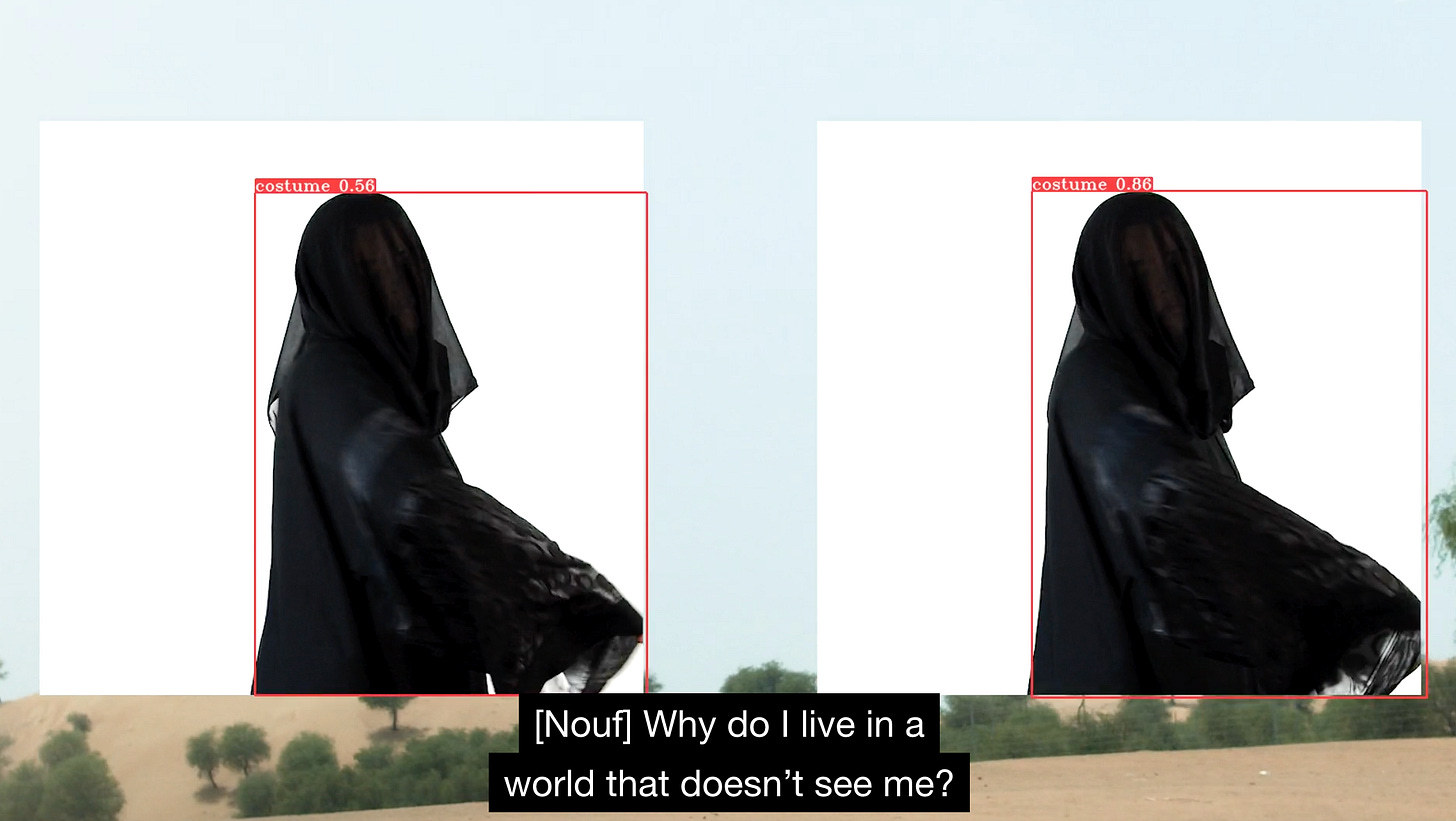

These questions come forward in the video art piece Ana Min Wein (Where am I From)? by Nouf Aljowaysir, where she makes a Sisyphean attempt to reveal information about her Saudi and American identities while in conversation with an AI program. Trained on evidently biased data, it responds that it cannot give her the answer she is looking for. Instead, it labels individuals as terrorists and their abayas as ponchos. She asks in the video, "Why do I live in a world that doesn’t see me? Why do the forces that kept me hiding who I am persist today?"

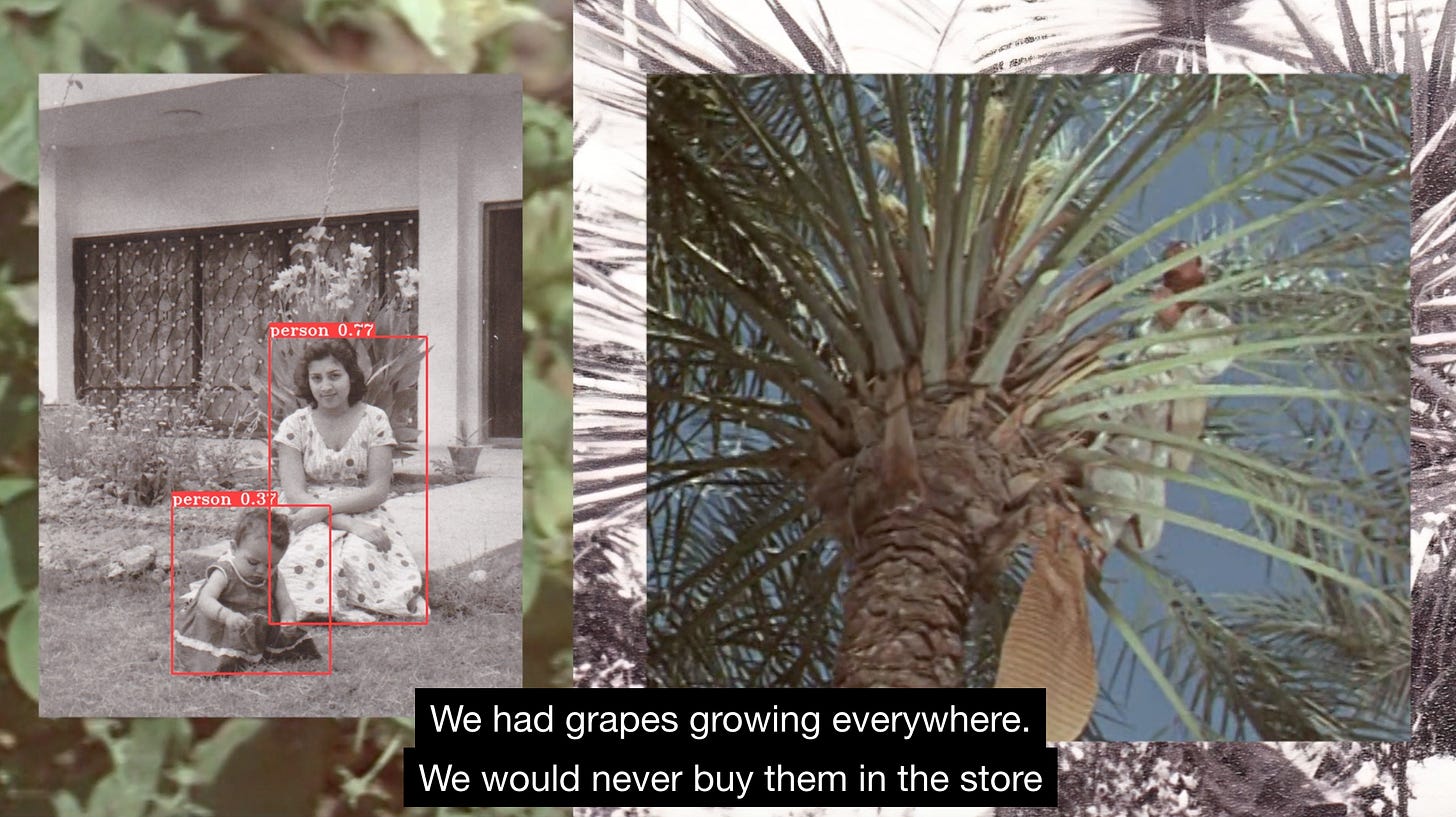

Halfway through, she begins describing her mother’s stories about growing up in Iraq. In response, the AI reveals a Google image search of Iraq that bears pictures of pain, war, destruction, and people in protest. Built from her mother’s stories and old photographs, Aljowaysir’s perception of the country is very different. In Arabic, her mother conveys how her old bedroom overlooked a beautiful river called the Shatt Al-Arab and, in their garden, how “grapes [were] growing everywhere.” Family photographs and cinematic clips play in the background, depicting serene moments in time that, in the social imaginary of Iraq today, seem distant or even incomprehensible. In drones, the machine’s “vision” works with immaculate precision to target individuals there, but it can’t seem to recognize the setting of Aljowaysir’s images. Her attempt at using the AI in an unconventional way by reimagining the past really only contributes in erasing it.

In a similar practice, art historian Diana B. Wechsler studied her family photo album containing images of destruction in Berlin just after the end of World War II within her text Migrations as a State of Being. She examines how, as time passes, the social imaginary tends to change, forget, and move on. It can be difficult to imagine Berlin just after the war without images like these. When constructing narratives about the past, it is helpful to “take some recovered fragments from that past to make an impact in the present in the way of a ‘profane, disruptive and powerful illumination.’” Human comprehension and a nuanced analysis of historical images are what help make this illumination possible. Citing Walter Benjamin, it is “about ‘seizing hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.’”

She wrote the text with an intention of positioning the role of art as "enhancing the experience of the world." Artists can guide us towards different perceptions than those with which we are accustomed. They have the ability to break away from the "established," "archived," "ordered" view of the world and question existing power structures. Wechsler describes these as imposing an "inside-outside situation in order to express ownership, belonging, or their opposite," referring literally and figuratively to borders–a phenomenon that also is embedded within the coding and data used to power technologies such as artificial intelligence. Algorithms work in a way reminiscent of the barriers Zygmunt Bauman also asserts in Wechsler’s text: "physical and symbolic, [they] are a declaration of intent meant to establish positions, define points of view, and to both include and exclude."

Aren’t these technologies simply representative of the power structures that trained them? Since data is based on language or images alone, a representation of reality by an AI program tends to remain a shallow depiction. In any case, quoting Jacques Rancière, Wechsler describes how what is “real” is always "the object of a fiction, a spatial construction where the visible, the speakable and the feasible are tied together. This notion of the real is suitable for a reflection upon the particular condition of the ‘uncertain state of exile’." She confirms that human perception and thought are constructions made by those in power, established through language, or the speakable, feasible, and visible.

How might certain ideas, visions, and imaginaries of “truth” be sustained or worsened by AI technologies? How are our perceptions of these programs in and of themselves being constructed by those who dictate how powerful it is, and how it should or should not be used? Machine learning was initially developed for low-stake situations such as web searches and online advertising, but when algorithms begin to radically affect human lives–in terms of arrests and air strikes, for example–questions of accuracy and accountability become crucial. Wechsler’s "state of uncertain exile" can be applied to individuals categorized when they are unwillingly confronted with these new technologies (algorithms for job or university applications, facial recognition, drone strike technology, predictive policing, to list only a few examples) that quietly but powerfully continue making their ways into society.

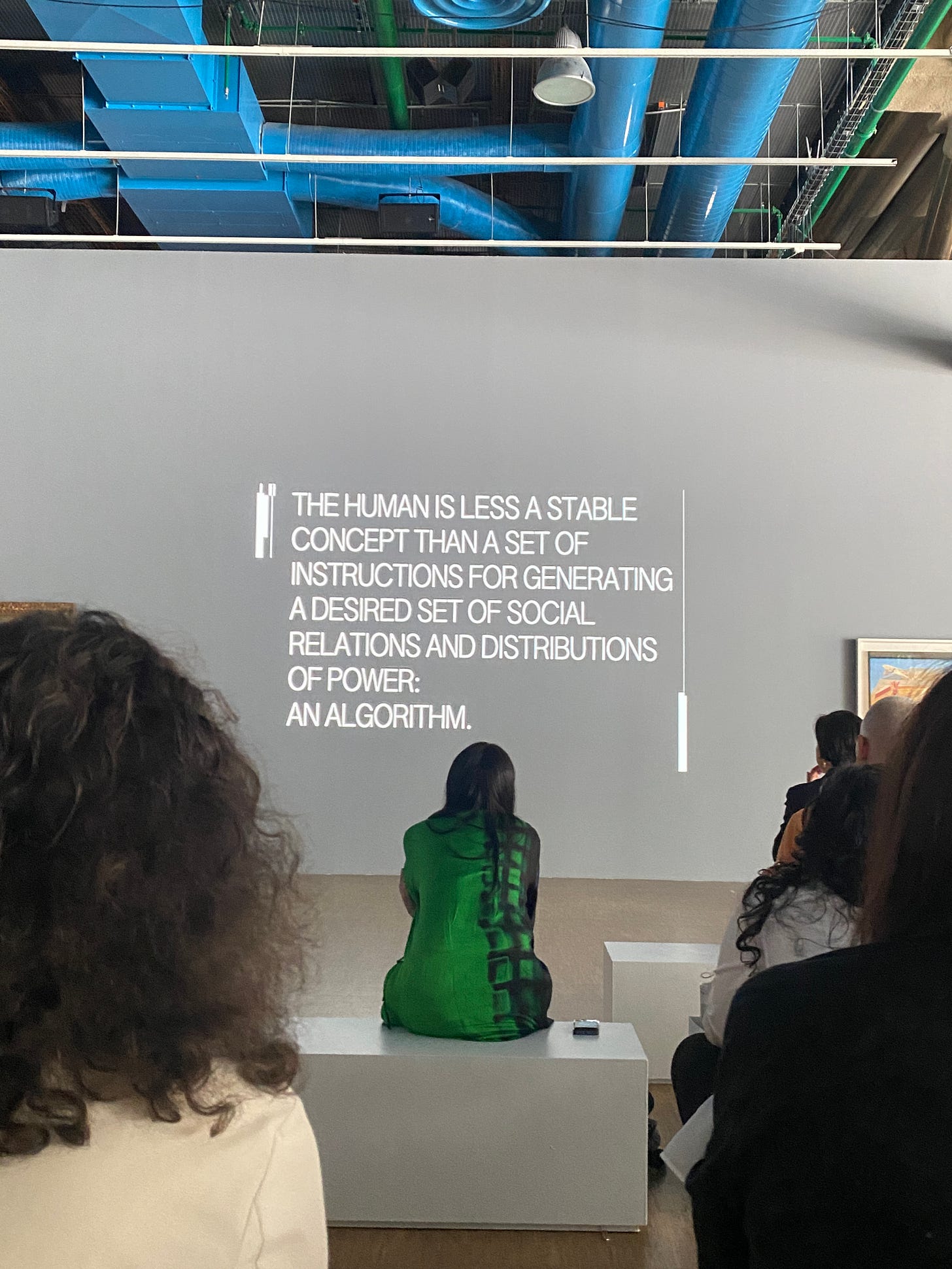

During a performance-reading of her speculative fiction novel, The Institute for Other Intelligences, at the Pompidou Center in Paris last year, Mashinka Firunts Hakopian asked viewers to recognize the weight of two ancient, but crucial terms in contemporary society: "technology" and "algorithm," the latter originating from medieval Persia. If we are already talking about the singularity and AGI, by comparing stochastic parrots to human intelligence, besides regurgitating old data, are these companies forging towards anything truly new? If we are going to anthropomorphize the machine, will it reach the historically varied and subtle nuance that humans have? Stories are passed down from generation to generation with emotion, intuition, grief, and trauma. The machine cannot feel these things. They are not quantifiable. During her performance, Hakopian revealed how an idiom written in another language—she gives an example of a phrase from her native Armenian—is all it could take to overwork and effectively crash a futuristic, "omniscient" AI program. At present, language and nuance are a way for Big Tech to spread Western values and convince us that these programs are divine beings, while also remaining their Achilles heel.

Brilliant, insightful, thought provoking. Sending around.