Noura Tafeche and Basem Kharma

This text was first pubished in Italian: Arabpop: Rivista di arti e letterature arabe contemporanee (Palestina #6) in May 2024.

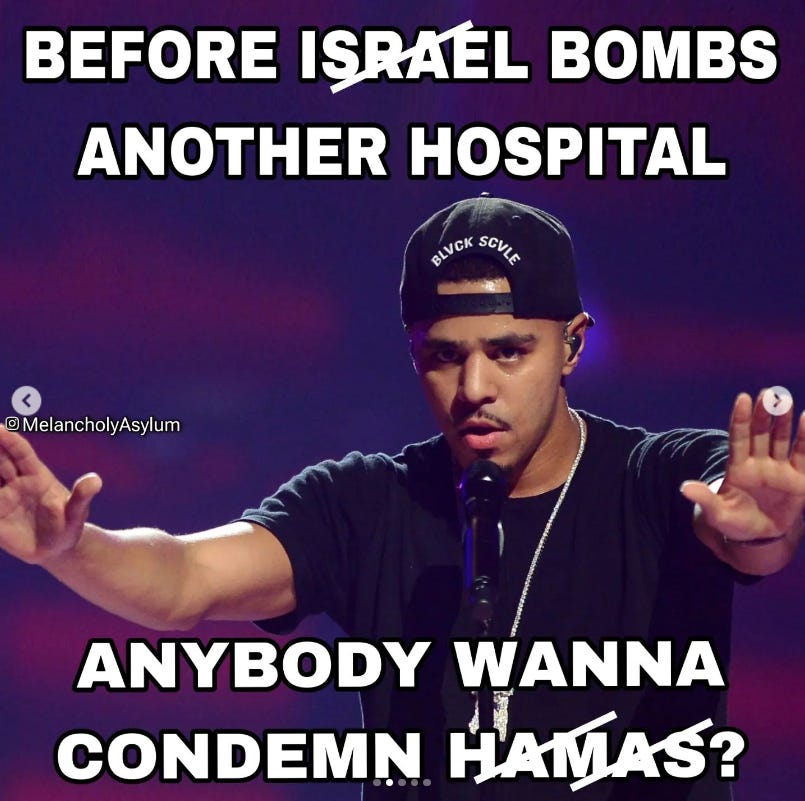

In recent months, the question most frequently directed at us Palestinians, repeated like a mantra by major Western media outlets, has been: "Do you condemn October 7th?".

If the answer is affirmative, end of discussion.

There is scarce genuine intent to engage Palestinians as active interlocutors in public discourse, instead, their sole function, at the present moment, is to confirm the existence of two types of Palestinians: the good and the bad.

The ‘good ones’ are to be saved, elevated as role models, victims of the violence perpetrated by the ‘bad Palestinians’.

They remain ‘good’ as long as they conform perfectly to the image the West has crafted for them. Good as long as they prove an utter lack of independent thought, as long as they show reliance on Western support and aid for survival. Palestinians must be helped because they are seen as children, incapable of self-sufficiency and living on their own.

This sort of infantilization is artificially counterbalanced by the category of 'bad Palestinians,' who are not even regarded as human beings but, as described by ‘israeli Defense Minister’ Yoav Gallant, they are "human animals."

They are stripped of any reason and motivation, with nothing they say being logical or well-considered, as all they supposedly are driven only by a craving for primal violence.

This distinction, however, dissolved precisely at the moment when ‘israel’’s intent transitioned from the "mere" framework of colonization to the deliberate enactment of genocide. While colonization relies on maintaining a segment of the colonized population tied to the colonizers through economic interests, genocide permits no such distinctions.

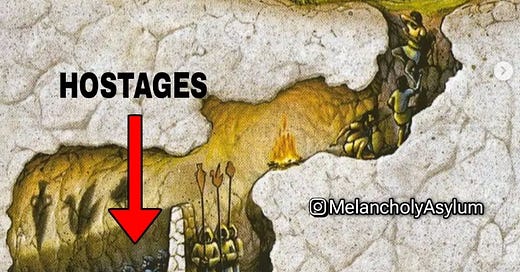

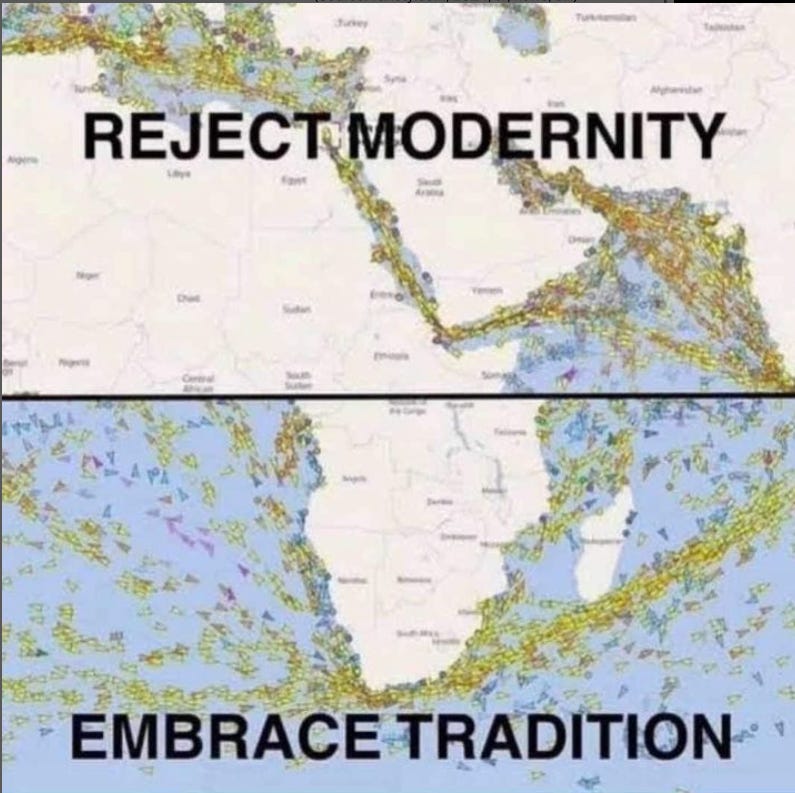

It is within this context that the key figures of the meme community operate. In defiance of the West's refusal to grant Palestinians any platform, the meme community carves out its own. What memers do is critically reclaim such narratives and tools : you consider us children? The real children are your soldiers, walking around in Pampers.

"Arabs Can Meme"

In June 2020, the Instagram page green_scare made its debut introducing itself with the bio "Post Arab Content". Its username nods to Red Scare, the US-fueled paranoia of the 1950s that stoked violent anti-communist sentiment. The complementary green hue may reference the symbolic color associated with the Al-Qassam Brigades and Islam, though this connection is left unstated, likely as a precaution against potential censorship.

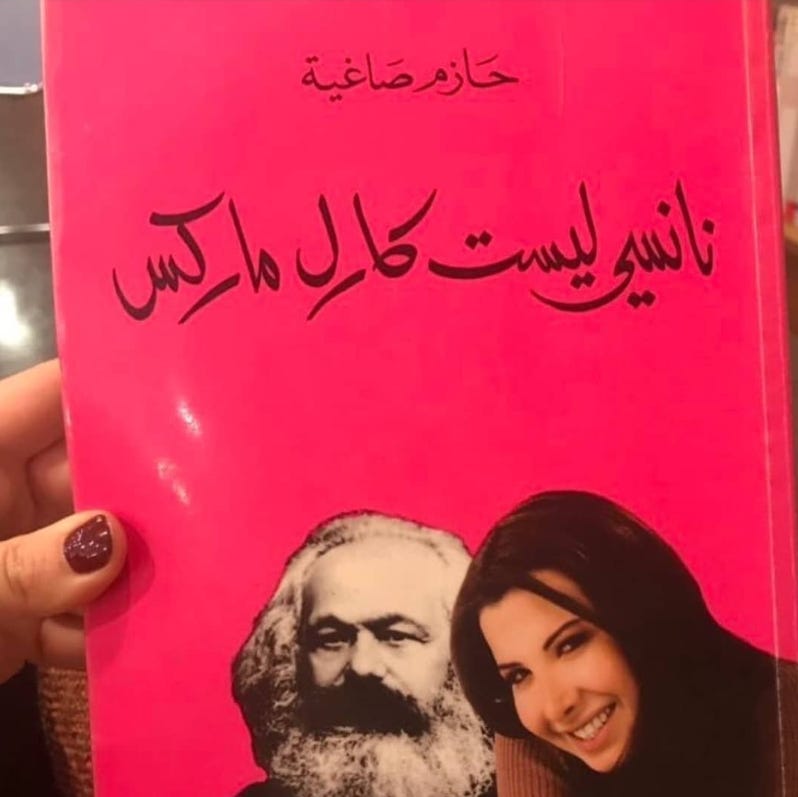

Some of the page’s memes feature captions in both Arabic and English, with extensive references to Arab popular culture – such as a picture of singer Nancy Ajram pasted on the cover of a book alongside Karl Marx – or repurpose exploitable webcomic templates that upend usual expectations, transforming them into acts of desecrating, multilayered analysis.

Another post-ironic page of social critique is fake.sa3id aka young gamal (account suspended or removed. Last update January 2025) – featuring a profile photo of Edward Said, with "🇵🇸 pan-Arab Marxist shitposting" in bio – from which we will borrow a meme that we will discuss further. By now, we simply note how figures of Palestinian authors and intellectuals are often used in memes to reframe their roles as ventriloquized pop icons, as if they were still alive and could express themselves through meme’s codes.

Focusing on the target audience of this micro-community, it’s noteworthy how, in the comment sections of some posts, various users ask their "internet family," in an old-school forum-like manner, for translations from Arabic to English.

These users might include Arab people from the diaspora who are not Arabic-speaking, as well as random individuals/users with no connection to the Arab world but who want to enter the bubble and understand what's being discussed.

These pages, in our opinion, are created with the intention of not being accessible to everyone. They tend to have relatively small followings—just a few thousand—and it’s intriguing to consider the journey that those disconnected from the Arab world must take to interact with these contents. Audiences must independently develop methods to grasp the meme and its underlying irony, educating themselves about its historical context.

The reverse doesn’t happen: on these pages, no explanations or educational efforts are extended to outsiders unfamiliar with this history.

Should the target audience shift – namely, the Arab and diasporic communities, along with those still holding onto hopes for change, despite the disillusionment following the 2011 revolutions – both the message and content of these pages would undoubtedly transform, thereby altering the very essence of their existence.

These pages occupy a space within a broader debate that often excludes the groups directly involved in the historical and media narratives being critiqued, such as Arabs or non-Anglophone subjectivities. By doing so, they add depth and authority with their sharp, incisive, and unconventional commentary, offering to the Arab community—by the Arab community—a more accurate representation of a non-Western zeitgeist.

This enables the communities to express themselves and recognize their own political formulations in ways that resonate more authentically with their lived experiences.

In the Belly of the Meme

These meme pages have consistently carried a distinctly judgmental stance towards both Arab and Western regimes, seen as jointly responsible for the current Arab condition. Their irreverent satirical tone has always been tinged with a bitter undertone, an unavoidable reality, given the fragmentation and economic devastation of countries like Syria and Egypt.

However, after October 7th, a significant turn occurred: a collective awareness emerged since we were witnessing a pivotal moment in history. This brought a renewed sense of confidence in the potential for popular resistance, extending beyond cultural realms, assuming an increasingly tangible presence.

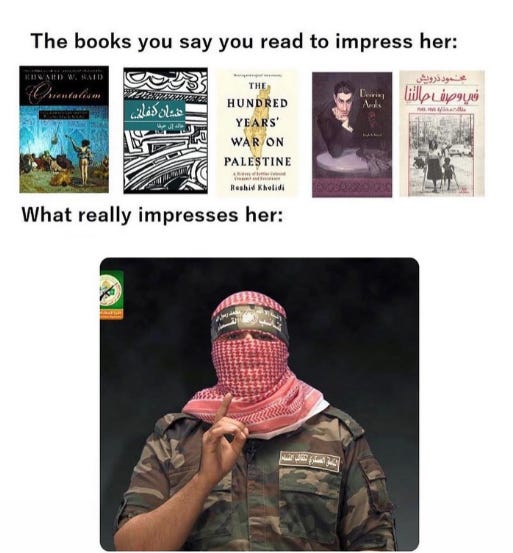

In the memescapes, a new emblem of this transformation is embodied in the figure of Abu Obaida, spokesperson for the Al-Qassam Brigades. His prominence stems not merely from his media exposure but rather from what he represents: a rejection of intellectualism for its own sake.

Culture, when it fails to produce knowledge for the benefit of the oppressed and instead is crafted for consumption by Western circles, ends up subjected to the same criticisms often directed at NGOs. Just as NGOs have been accused of reducing the Palestinian cause from a political struggle into a predominantly humanitarian issue, intellectuals have contributed to its fragmentation.

In contrast, there has been a growing celebration of what is perceived as the most immediate tool for achieving tangible results: armed resistance. This resistance finds its primary symbol in Abu Obaida. The fact that his identity remains unknown allows him to embody all Palestinian fighters. He is, at once, one, no one, and one hundred thousand.

This universalizing anonymity mirrors the broader history of the Palestinian struggle.

In the past, the fiday, or freedom fighter, was the emblem of the resistance, and the defining characteristic of the fiday was that anyone could be one.

The same applies to the figure of Handala. Created by artist Naji al Ali, the character of a child seen from behind, embodying collective identity and struggle, to symbolize that this child represented all Palestinian children.

In memes, the contrast drawn is twofold. Externally, it’s between the Palestinian fighter and the occupying soldier, whose fate is sealed when facing a fiday, someone who owns nothing —fighting the occupation in sandals, as some memes suggest—yet possesses everything.

Internally, the confrontation, it’s between those theorizing resistance and those actively resisting. If the former can become the subject of memes, the latter are spared criticism, as evidenced by Basel al-Araj—a militant intellectual who was killed in action while fighting the occupation with weapons in hand—remaining excluded by meme commentary.

The Politeness of Interpretation: High Culture vs. Popular Culture

The image carries a density that surpasses the word.

Through memes, one can express wild and merciless truths that grammar would demand be handled with greater caution.

This idea is echoed in Critical Meme Reader II (2022), published by the Institute of Network Cultures, which humorously notes: “Leftist meme be like: [a 3000-word essay crammed in one image],” mocking the leftist obsession with hyper-theorerized pedantry.

The Arab decolonial memetic space does not engage in efforts to challenge European moralism, nor does it require the "courage" to speak its truth. Terms like challenge and courage imply the existence of a rival.

In contrast, many of the meme pages we’ve discussed operate independently. They feel no obligation to explain or justify themselves, relying on validation, nor do they concern themselves in the slightest with being accountable to anyone. None of their posts seek the approval of the conservative European moralist mindset, which would react with outrage at the sight of a meme like those from shabjdeedsarcasm and melancholyasylum.

Outrage, however, does not arise solely from ideological polarizations. At times, the bigoted wave also manages to reach those preachy leftist, self-perceived progressive, academic circles, particularly those aligned with interventionist and colonialist frameworks like the “two states for two peoples” rhetoric.

Palestine is often idealized and elevated to a concept cherished by "high culture," but rarely considered as a practical idea demanding concrete action: demonstrating tangible support for its liberation and offering unconditional backing to its resistance. Instead, Palestine becomes a passive element to be speculated upon, a subject to be theorized about with detached relativism, and ultimately, a realm for professional parasitism—no longer seen and treated as a living matter, but as a relic, dead and preserved, fetishized for the consumption of PhD pursuits.

Let’s momentarily shift our focus from the sharp sarcasm of these memes to the quality of our reactions.

When we resonate with that biting irony, it’s because we’re seeing and embracing the same perspective on reality that the meme encapsulates — a twisted sur/realism disrupting the gross, unquestioning, flat adherence to the dominant Western narrative that has been fed to us.

Laughing at and sharing a meme from fake.sa3id with our friends, believe us, is not just liberating—it is an act of justice in itself.

The Prevailing Anglophone Influence on the Internet

The internet environment was conceived in the English language.

Rarely does one see, in lists of privileges (authored by non-privileged individuals), the prerogative of being a native or fluent Anglophone.

The linguistic hegemony of English has a history rooted in over four hunderd years of imperialism, stretching from the late 16th century to the second half of the 20th century—a career built upon a repertoire of violences, encompassing land theft, genocide, slavery, subjugation, exploitation, and the erosion of local linguistic diversity in favor of one single tongue, akin to One Ring to rule them all.

It has bowed to this monolinguistic hegemony, first in commerce, the economy, courts of law, journalism, the academic world, and not least the virtual home, the internet.

English is the lingua franca of the web, theoretically allowing localized content to reach broader, transcontinental audiences.

A real, balanced, and equitable multilingualism in the world and on the internet is still to be considered a utopia. Any aspirations toward such a structural rethinking are little more than rebellious twinges in an enormous, overindulgent system too comfortable and bloated to notice its minor spasms.

Since the 1980s, the poet and novelist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o has chosen to write all his narratives in his native language, Gikuyu, reserving English for essays and polemical pamphlets.

Hence, a paradox frequently underscored is that his global renown is in fact indebted to the very language it seeks to resist, and that this opposition to the encroachment of the dominant language must, ironically, be articulated in English itself in order to gain any meaningful resonance.

In addition to being a presumptuous, smug assumption, the opposite is equally true: it is the Copernican challenge to domains commonly deemed international—simply because they are self-proclaimed as such—despite actually representing only a specific portion of the globe. This allows for the liberation from the Eurocentric yoke, paving the way for a truly international perspective.

Many publications on the genealogy or politicized rise of internet meme culture—ranging from academic dissertations to lifestyle magazine—begin by emphasizing the foundational significance of internet historical turning points such as the 4chan platform, the Capitol storm, Pepe the Frog, Donald Trump's election, QAnon, Pizzagate, the Proud Boys, the alt-right, and any extremist or grotesque movement that, originating in the US mythos, is automatically subsumed as a imperative subject of study by contemporary global historiography.

Researchers of digital cultures themselves perpetuate the notion that internet’s archaeology, when not focused on kitty videos, originates from a political history claiming worldwide relevance. In reality, it reflects phenomena limited to a selective part of the planet, which is given disproportionate attention and mystifies the true relationship to the global-scale context.

If internet archaeology were authentically as universal as it purports to be, it would need to account for the other by recognizing the existence of an ethno-memetics, echoing a critique raised by Professor Hamid Dabashi.

In a 2013 Al Jazeera article titled Can Non-Europeans Think?, Dabashi questions the dichotomy in which European philosophy is universally acknowledged as "philosophy," while African philosophy is relegated to the term "ethnophilosophy" : “Why” Dabashi asks, “if Mozart sneezes, it’s ‘music,’ while the most sophisticated ragas of Indian music fall under the category of ‘ethnomusicology’?”

Dabashi alludes to an ideological construct that remains largely intact, namely a vestige of intellectual imperialism, from which the Anglophone world continues to derive privilege and benefits. He highlights how European thinkers are still perceived as universal precisely because they operate within a context that was—or perhaps remains—imperialist in nature.

Building on these premises, within the online sphere, reappropriation entails a firm insistence on the establishment of new systems of imaginative production, both linguistic and aesthetic, to be deployed across multiple virtual fronts.

Memes at the Sunset of Eurocentrism

Social media are inherently unequal digital environments.

The illusion of the internet and associated platforms as free spaces has been shattered and definitively died with the exposure of major scandals like Facebook-Cambridge Analytica in 2018 and the growing influence of corporate megalomaniacs and their acolytes.

Still, that hasn't stopped networks from pushing forward, communities from speaking up despite the unavoidable restrictive terms and conditions, and resistance movements from self-documenting when no one else will—just look at the stories of Palestinian journalists, whether they're alive, survived, or murdered by ‘israeli’ and Zionist terrorism, during the first live-streamed genocide ever.

The mere occupation of these online spaces by anonymous communities or individuals—like, for instance, arabs_with_identity_issues_2—sparks a semiotic counterbalance that cultivates politically charged digital spaces. These spaces fuel another transformative dynamic: that the spotlight on the Eurocentric, imperialistic imagination, with its arrogant, withered, and denialist pride, may finally fade.

The meme becomes, once again, a subtle agent of political representation and change in the hands of a community that can’t be easily crushed and refuses to be silenced. We are no longer victims of a narrative; we are the active authors of it. And we trust that this will be our future.

Basem Kharma is a PhD candidate in the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Milan. His doctoral project investigates the activities of Palestinian movements and parties in Italy and their relationships with Italian left-wing organizations. His research interests focus on the history of the Arab world, the history of Arab socialism, and, in particular, the history of the Palestinian movement.

Noura Tafeche is a visual artist, author, onomaturge and independent researcher working in between installations, videos, neologisms, archiving practices, laboratories, experimental applied methodologies and miniature drawings. Her areas of research expand on the subjects of visual culture and its techno-political implication with a focus on operational images, digital militarism, online aesthetics, internet hyper-niches and meme culture, philosophy of language and visual representation of speculative imaginaries.