I watched the trailer for the upcoming film by Alex Garland titled Civil War when it came out in mid-December (the film will be in theaters in April). Curious about the reception of this trailer, I viewed and read many, many reactions to it, most of which popped up within a few days of the trailer’s release. I believed that doing this would give me a lay of the land relative to – if nothing else – what this trailer made people think about in this time period. The reactions to this trailer revealed to me that many people have largely become either unwilling or unable to engage in good faith with fiction, with film and its accompanying images, and also with ideas that sit outside their own beliefs relative to truth and reality. This disability appeared to have no political bias – I watched and read reactions from people all over the political map – nor was it related to the reviewer’s age or experience in reacting to movie trailers (meaning that people and publications with large followings and readerships and also people with only a handful of followers – including reddit posters – all exhibited, with rare exception, this kind of thinking when analyzing this trailer).

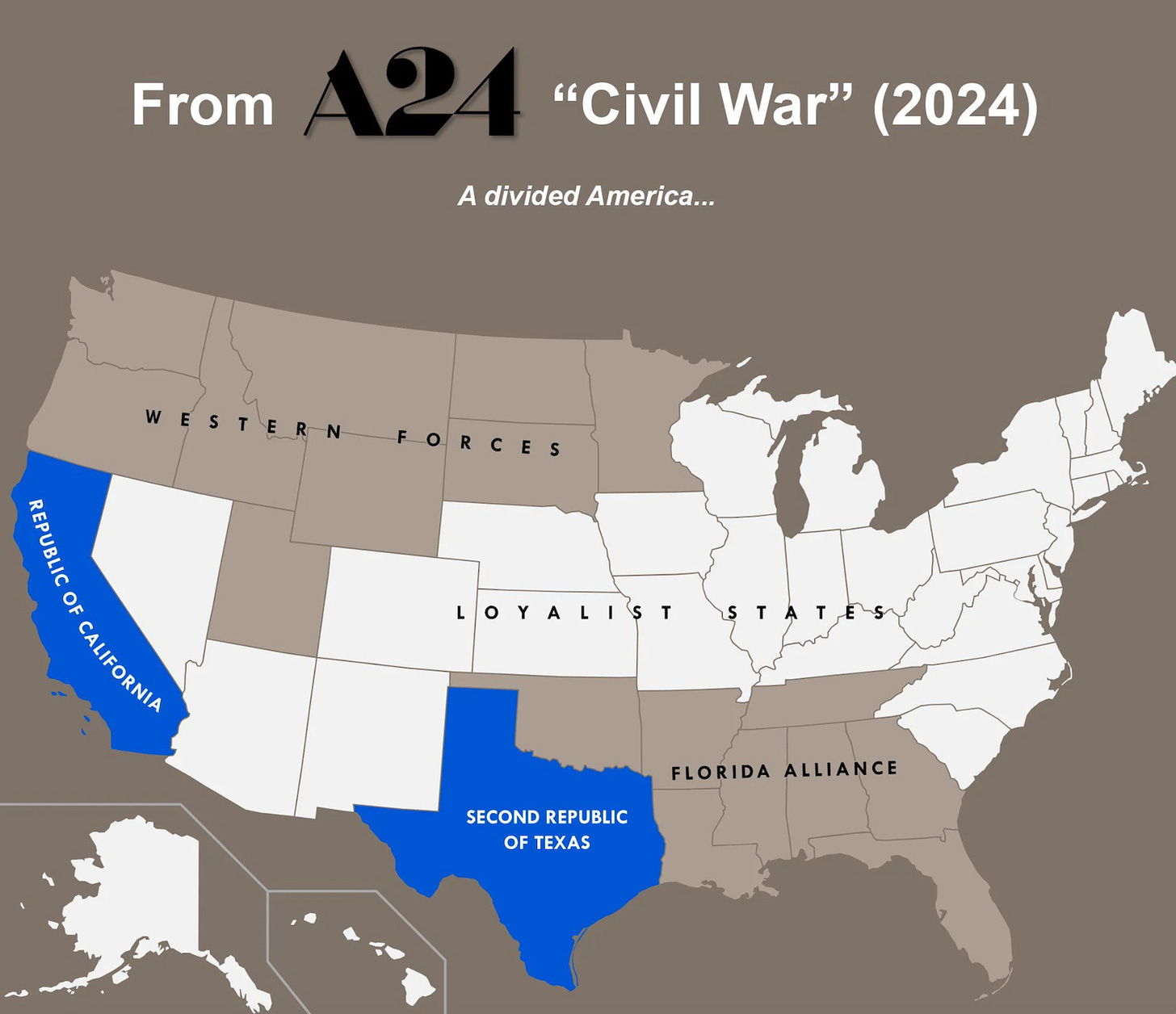

In the trailer, we are shown a fictional United States in the midst of a civil war. Almost every reaction I encountered seemed to reveal the belief that this film was in some way meant to depict the manner in which an actual civil war might or will go down in this country, and criticized the trailer for being inaccurate in its depictions. Most of these reactions (as well as their viewer/reader comments) focused on the fact that the film depicts an alliance between Florida and California, which the film calls the “Western Forces.” Well-known sources including the AV Club and the left-wing Twitch streamer HasanAbi noted the “inaccuracy” of this, with both parties alluding to the fact that Alex Garland is British, obliquely suggesting that he might (by dint of his nationality) not quite accurately grok the contemporary political landscape of the United States. The reaction to the Western Forces inspired Vice to publish a piece defending why this alliance could be credible, and other reactions suggested that this trailer was either an erroneous analysis of a factual future event – “Texas has not aligned with California. It’s not happening” – or a poor interpretation of the contemporary lore of the United States: “Putting aside all the other reasons why this doesn't make sense, why do they call it something as boring as ‘Western Forces’ and not ‘Cascadia’ after the real life independence movement that covers part of that area?” Comments like this harkened, for me, the critiques made by authors and consumers of fanfiction, and their tireless efforts to accurately characterize and historicize their favorite fiction’s “universe” by canonizing key motifs – and correcting anyone and anything that doesn’t accurately reflect the canon. The fictional universe here isn’t Hogwarts or Assassin’s Creed, however, but the contemporary United States, which has now been lore-ified.

Some reactions also suggested that this film was potentially encoded with a conspiracy theory known as “predictive programming,” which suggests a secretive government intervention that is meant to prepare audiences for the reality of what is suggested in the film (this was also noted by The Hill). One reactor that I appreciated stated his biases clearly, and his reaction was more a creative exposition than anything else. It was made by a former boogaloo boi and current firearms aficionado who explained how, in his boogaloo days, he too once longed for a civil war, before he matured and made positive changes to his life that allowed him to understand how detrimental such an event would be. He also pointed out a motif in the film that seemed plausibly (and no doubt intentionally) boogaloo-coded, which I personally would have never picked up on. Unlike other reactors, he also revealed what his ultimate criteria for judgment of Civil War (once it came out) would be the accuracy of the different weapons used in conflict. He stated that if “they” got the tacticals “wrong” it would “take [him] out of” the experience of the film, meaning he’d be too busy critiquing the choices of the filmmaker to feel sucked into the experience of the actual movie.

So why should I concern myself with what people have to say about (of all things) an upcoming film trailer? In Vilém Flusser’s Communicology (published posthumously in 2022), the Czech-Brazilian philosopher presents an analysis of our contemporary relationship with what he terms “technical images” – defined, broadly, as all images that are not composed by the human hand, including maps and blueprints (along with more obvious examples like photographs). In this text, which deepens ideas Flusser laid forth in his 1985 book Into the Universe of Technical Images, he categorizes our relationship with this form of image as “pseudo-magical,” replacing an ancient connection between humans and what he would call “traditional” human-made images, a relationship which he qualifies as legitimate “magic.” He, and others: In his 1951 book The Social History of Art, Volume 1 From Prehistoric Times to the Middle Ages, Marxist art historian Arnold Hauser explains the genesis for this magical relationship between human and human-drafted image, stating that the cave paintings “...were part of the technical apparatus of this magic; they were the 'trap' into which the game had to go, or rather they were the trap with the already captured animal – for the picture was both representation and the things represented, both wish and wish-fulfillment at one and the same time.”

In Flusser’s view, technical images do not have the capacity to reach toward the depths or heights of such magic, yet viewers (us) choose to view them unquestioningly as possessing the same power. Says Flusser, “The climate of mass culture is pseudo-magical because the inability to decipher technical image programs is not a technical difficulty (technical images are not mysterious) but a refusal to decipher them on the part of the receivers (they are believed with bad faith). The explanation is that people fear to see through the programs they are fed: they prefer semiconscious reception to the responsibility of full awareness. And this fear is justified: The conscious use of technical imagination would undoubtedly imply the abandonment of experiences, values, and knowledge cherished for countless generations.” Essentially, while our entire epistemology relative to creating, dispersing, and receiving images has completely changed since the invention of the technical image – which invited a third party into our relationship with images, in the form of the apparatuses that create and disseminate and make sense of these images – we have never given any serious thought to the way in which this change might demand a different form of relationality between humans, the apparatuses that create technical images, and the images themselves (which now fairly dictate our lives).

More and more, we regard images as the representatives of not just our identities and our experiences but also our beliefs, and we must believe their lore (meaning that an image’s real or imagined linear narrative must work coherently with its optical coding) for us to continue to have a healthy relationship with them. Untethered from a lore we find fathomable, they start to resemble what? Enemies? The anti-magical? The un-lorified? If the internet and all other apparatuses and programs that make and then scatter technical images are the great sensemakers of the 21st century, they are certainly untethered to a system of logic that would attempt to unite or synthesize differing humanistic belief structures under an umbrella of similitude. And this brings me to another conflict that’s playing out in real time now, with real people dying and actual political factions, versus fictional ones like the Western Forces. I teach at the International Center of Photography, and in the fall one of my now-former students, the photographer Jesse Kornbluth, wrote an essay for my course that was partly about an image of a baby’s arm sticking out of rubble in Gaza.

This image, which is deemed sensitive content and protectively screened by Instagram, was posted by the law professor and scholar Khaled Beydoun, who has over 2 million followers on Instagram. It was posted without a photographer’s credit.

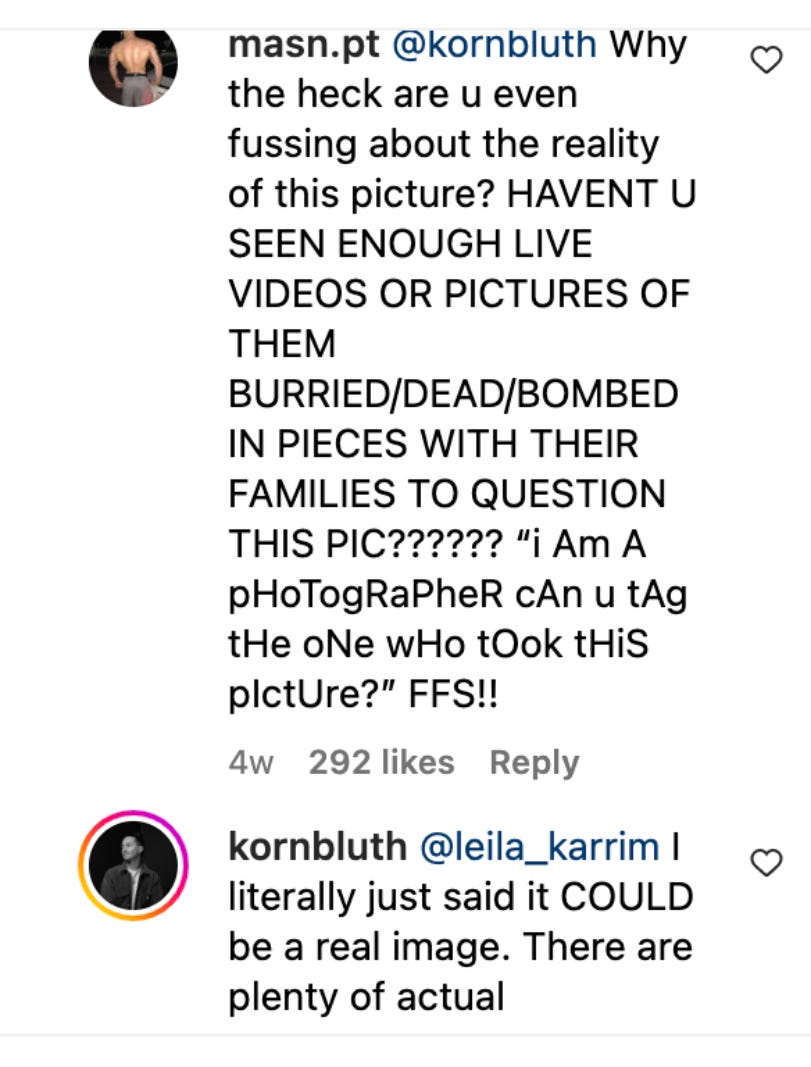

Kornbluth questioned the authorship of the image in the comments, which – despite the accompanying text written by Beydoun, which presumes the child’s identity as female – looks very fake. Within the culture of photojournalism and documentary photography, identifying an image by tagging a photographer is standard practice (and asking for a tag when one appears missing is also standard practice), because this is a world that foundationally approaches images as truth-telling documents – the historical, linear programming defined by Flusser. Kornbluth’s query received many positive responses, and also many negative ones, for apparently daring to question the veracity of this image.

Other responses made the claim that this image was so much in line with countless images of Israel’s bombings of Gaza – and perhaps more so with the linear, non-photographic narrative of “what is happening” in Gaza – that Kornbluth’s query was itself moot: it didn’t matter whether the image was “real” or not. There were enough verifiable and identically terrible images and reports of atrocities to warrant its validity. A small battle in the comments section of this post was waged, something less about the idea that this image was “real,” meaning captured via photographic device by a human and duplicated in as truthful a manner as possible, and more about the notion of plausibility in general. The argument against Kornbluth’s request for the owner of the account to tag the image with the photographer who made the image was, essentially, that Kornbluth was taking viewers out of the experience, out of the moment, out of the true story that substantiated the (to my eyes at least) fake image – a view that mirrors the former boogaloo boi reactor’s desire for Civil War to showcase the “right” kind of weapons so as to not force his critical capacities to override his passive receptivity.

The counter-argument is that an image so obviously constructed already takes you out of the truth – if you’re involved in the field of photojournalism, you expect for conflict images to look real, not like AI, and to be credited accurately. You expect atrocities to be documented properly, for the truth of a war crime to be both sought and unearthed under the rubble and death by people brave enough to risk their lives to do that job. That is no longer a realistic or viable expectation. As Flusser states in Communicology, “If one considers how specialists manipulate technical images, both on the elite and mass-media levels, one can observe the formation of a new form of consciousness and action. They are new in the sense that they are no longer linearly programmed. Categories such as sooner-later, if-then, true-false, or real-unreal do not apply to it. Other, non-dialectical categories, such as proximity, point of view, or the other, form the structure of this way of experiencing, knowing, and evaluating.” The argument that the creator of this image (whomever that might be) makes, and that is remade by the poster and by the commenters who defend it, is that this image is now above all a righteous point of view, and that it is this point of view – and not what is depicted – that is the ultimate truth.

From this, I would argue that the actual content of technical images (however it may presently dictate and dominate our lives) is becoming almost beside the point – what is more important is what is read into them (this coincides with Flusser’s belief that, “Linear texts were originally invented to describe images, and thus served as a function of images, but the relation of this function proved to be reversible, and images were soon used according to texts.”). In 2011, I interviewed the German Conceptual artist Hans-Peter Feldmann. Known for collecting specific types of images and placing them together in ways almost algorithmic in direction, Feldmann (who is now deceased) came from a time period when the scarcity of technical images was what made them so compelling. As he told me, “After World War II, there were very, very few pictures in Germany. It was nothing like today. And it was actually the fact that there was such a small quantity of images around that made me so interested in them. The few I could get, I really wanted to see.” As a child, the artist would playfully snip pictures out of certain books and paste them into others.

Compare this to now, and both the specialness and also the arbitrariness of images feels almost identical – if images are far from scarce, the ones that actually attract our focus are fewer and fewer, and tend to relate directly to our individual experiences (a million pictures of people kissing mean next to nothing – the one you see of your former lover kissing someone new means everything). The difference could be merely one of proximity, which is to say relationality, as Flusser points out: “The fateful sentence love thy neighbor acquires a new meaning because the nearer, the more interesting. Love and hatred become integrated within knowledge as they never were during history; one knows what one loves and hates because it is near, and the less something interests, the less one knows it. This is, of course, far more human than the cold, objective attitude of calculating scientific reason. But it is not humane or humanistic: I am far more interested in the fly that bothers me here and now than I am in the future of eight hundred million Chinese, and I love my dog more than I love the suffering masses.” This push and pull of proximity (or at least perceived proximity) is one of the most manipulable aspects of passive reception of the technical image.

Going back to the trailer for Civil War, there was one reaction, ominously titled “A Film Depiction of a Coming Civil War…”, by a person (Ryan Chapman) with a comparatively high subscriber count (250K+) who describes himself as a “thinker of general human concerns.” Chapman delivers his reaction with an air of gravitas, prognosticating that the film is “...a modern depiction of what a civil war might look like in the United States.” He thinks that the film seems like a “milestone” and that people typically make films like this as a “preventative” measure (he does not back up this claim with examples). He also says that he can picture historians in the future saying that “things got so bad” that a film like this was released: “If this film was released 15 or 20 years ago, I think it would’ve caused widespread shock and even [seem] gratuitous, unnecessary, cheap… [now] the concept itself doesn’t have as much novelty as the filmmakers thought. It’s become somewhat mundane. A fact of life…” Never once in his catastrophizing presentation does Chapman seem to exhibit any understanding that he is speaking about a fictional film, one that seems very much at home in the director’s oeuvre of dystopian science fiction (Garland wrote screenplays for 28 Days Later and Never Let Me Go, and directed Ex Machina). The plot of Never Let Me Go revolves around human cloning, and Ex Machina is about a Turing test-style AI robot experiment. Both play on “real,” meaning extant, technological phenomena that are considered controversial in contemporary culture, and neither is predictive of nor preventative toward what might happen now or in the future with this phenomena.

Chapman, with his po-faced-yet-hysterical take on a fictional cultural product, infers the proximity of a civil war vis-a-vis the creation of technical images that he refuses to think about or describe as an artwork. In presenting such a take, he brokers in a uniquely irrational form of logic that theorist Jordan Hall terms simulated thinking – a habitual style of contemplation that attempts to absorb novelty and/or complexity into pre-existing narratives. Somewhat similarly, artist Brad Troemel terms this form of thinking and acting literalism, defined broadly as “A way of willfully misinterpreting metaphors by taking them as literally as possible. By ignoring context and intent, literalists are able to reframe the debate around culture by casting themselves as righteous protagonists and their opponent as the embodiment of pure evil… Every literalist…believes their cause is righteous enough to warrant misleading exaggeration. The righteous ends always justify the bad faith means.”

In a time period where one often contends with the cynical belief that all artworks are just trojan horses for the artist’s own political belief system, both simulated thinking and literalism refuse to interact in good faith with artworks that are potentially value neutral or politically unburdened – or in possession of values and politics that don’t precisely mirror default political narratives splashed all over social media. These modalities of negotiating reality are directly in line with Flusser’s interpretation of how we have reconciled image and text in the age of technical images: “This general tendency toward infantilism and idiotization both on the elite and the mass level of communication, which prevents us from grasping the situation we are in (and which manifests itself as the tendency to blame others for it), is a tendency willed by all of us most of the time, because infantilism and idiotization (consumer culture) are evasions from the responsibility to embrace technical imagination. It is preferable to behave as if one did not know of the countless openings that our situation offers us and continue to let oneself be programmed (and at the same time complain about lack of freedom and meaningful communication) than to dare to face those openings and give up cherished categories (linear programs).”

The fact that Chapman reads so much latent intention into a film after having seen exactly two minutes and twenty-four seconds of its content can be seen as a kind of willful imposition of linearity – mirroring the thought structure of those (most of us, probably all of us) who don’t want to use their critical mind to “take them out of” their image-fed delusions. By allowing ourselves to get lost in – and to resist being taken out of – the images we look at, and by craving this delusion, we force a proximity that isn’t based in reality, yet feels real. In Communicology, Flusser questions why a television can’t be a “two-way channel,” and posits “...if thus changed, it would become a powerful tool for democracy and thus be far more revolutionary than are public meetings (let alone political elections). But such a change would require a new vision of politics, of decision-making, of action; it would involve the abandonment of concepts such as nation or class, and it would involve the abandonment of the present, highly satisfactory use of television. It would require a technical imagination that nobody is willing and able to mobilize, neither those who manipulate current TV nor those who are its victims. For this reason, not because of some technical, political, or economic difficulties, the current TV structures work as they do, as radiating amphitheaters.” The change Flusser idealizes suggests a kind of symmetric legitimization that would take us out of the theater of our own image-driven fabulations. It would also stand to reason that such a structure would drive us to trust the words of a Chapman-like figure over a film by a famous filmmaker like Alex Garland – because Garland would be, by virtue of his involvement with “elite” media forces, more likely to create something meant to manipulate to his viewers, politically or otherwise. Which is how many receive the message of an independent creator like Chapman; his credibility is inferred by his symmetry to his audience, which is erroneously assimilated as peer-to-peer (sponsoring what is likely the great romance of the 21st century: the parasocial relationship).

When Flusser questions why televisions can’t communicate in both directions the way that telephones do, I think that he is imagining the decentralized collective intelligence systems that are in the process of forming, as defined by Jordan Hall (in this work, Hall examines the change from broadcast to digital he defines as “network symmetric decentralized”). But it is the fact that so many of those who engage in this type of sensemaking still operate exactly as they might have during the era of broadcast that is itself a roadblock to understanding and creating technical images and developing the technical imaginary in a meaningful way – power extended to the individual who manipulates using textual narrative in the same manner that the media has always done is not a “better” imaginary, as shown by someone like Chapman (and also by those like Khaled Beydoun, whose humanitarian intentions, however noble, are buffed and smeared by the use of untrustworthy images that communicate ideology). Symmetry does not elide manipulation. Our technology and attendant programming can be made to better reflect what a technical imagination might look like, but we must first contend with the fact that many people who use images in realms of decentralized systems of intelligence are attempting to read a selective and static meaning into those images (just like elite media forces of the past), versus creating new scaffolds of intelligibility for those images (and also, potentially, new images).

Flusser’s words relative to our present dilemma perfectly encapsulate the dead ends we continue to encounter when living in an era of compulsive communication and default manipulation – and that the problem is mostly self-perpetuating: “The core of our crisis is that in those situations for which we are not adequately programmed we behave in a way that prevents us from understanding them, and we do so because we do not want to understand them. Mass media manipulate us, not so much because some hidden interests use them against us by some superhuman cunning but because we want to be manipulated. And we want to be manipulated because we fear that if we grasped the situation, we would lose the other side of our program, our historical, conceptual way of being. We allow the media to manipulate us for fear of loss of reason. We do not dare make the leap from linear thinking to technical imaginary thinking for fear of disintegration. Thus, we are, of course, easy prey to those who are interested in manipulating us: we collaborate with them. No use blaming those hidden forces for the situation we are in, not only because they are themselves victims of the same context we are in—they manipulate us because they were programmed for manipulation…” And it's no use to even think that there are “hidden forces” anymore, so thoroughly have we all been conditioned to operate within and through this manipulative capacity – it no longer presents as an us versus them scenario, but more an ouroboros of ourselves and our own compulsive fraudulence. Sometimes the state we are in reminds me of the story of the Polish emissary Jan Karski, who witnessed the liquidation of the Warsaw ghettos and was the first person tasked to inform Allied political leaders, including FDR, about the extermination of the Jewish people. Famously, when Karski met with the U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter to provide him with a verbal account of these atrocities, Frankfurter refused to believe him. When a fellow emissary insisted that Frankfurter take Karski’s testimony as truth, Frankfurter responded, “I did not say that he’s lying. I said that I do not believe him…. And my mind, my heart… they are made in such a way that I cannot accept [that this is true]. I know humanity. I know men. Impossible.”

Of course, it wasn’t impossible – and Karski would go on to be remembered as a war hero brave enough to tell a truth that the world didn’t want to hear – and honorable enough to be believed without technical evidence. According to his memoirs, Karksi saw himself as a “live phonograph record,” and felt it was his duty to tell officials exactly and precisely what he had witnessed. Today, many belief structures seem like almost an inverse manifestation of Justice Frankfurter’s, the man who could believe an individual human was telling the truth, and also believe that the truth described was impossible. We seem to believe images that are outright fictions or lies, and we attempt to reverse engineer a reality – however horrific – that would make these fabrications tenable. In Flusser’s view, “We are, all of us, committed to communication, which means committed to the future. We are committed to it even if we allow ourselves to be willingly alienated by radiated programs because it is this commitment that allows us to live: there is death in isolation. But of course, how can we commit ourselves to communication if it either isolates (technocratic totalitarianism) or is indecipherable (technical imagination)? How can we commit ourselves to a future (a culture, a codified world) if it is either meaningless or dreadful? This is the situation we are in.” And it is. I have the pictures to prove it.

ohhh yesss, but stilllll, my world is dreadful but not meaningless, factuality and meaning two different things as you note. art is the most meaningful by not being factual. Re. fact there are still plenty of people in the real world who transfer information to us, and more and more we will have to depend on them, which might be good. when we can't tell which are the robots, it won't be technology or the deep or shallow states' fault, it will be ours for blaming everything on these global trends and losing ourselves to abstractions that mirror the machine's immaculate conceptions. In my opinion, it has always been war between the machine and the human being with the former in charge. One can only try to save one's own soul and be a light to the world the neighborhood or one's dog.