Sarah Wambold

Rem Moore

Capital has the effect of rendering us dead before we've drawn our last breath. Online, we constantly interface with non-human, capital-driven profiles of the living and the dead. As our online activities become increasingly commodified, so too are our interactions with death also shaped by commodification.

Not long ago, a static memorial page might have been the only form of death we encountered online, typically built on a platform owned by a multinational tech corporation. The profile would be made by those close to the dead and interacted with by those visiting the page, posting a message or photo, or sharing the link. Those memorial pages, despite their disclaimer as a profile of a person no longer alive, and therefore not active on the platform, continue to be data-mined by the platform seeking ways to monetize the activity of those who engaged the memorial. This surplus production of afterlife value, in the form of continued advertising revenue and trained data sets, is an ongoing gain for the biggest corporations to ever exist. The rest of us simply continue to experience loss.

Our way of being alive online has become less distinguishable from how the actually dead are represented and packaged to us. There is a related debate around how much agency we have online, particularly as we are able to be reposted, trained on and regurgitated as personalities even without our deliberate input. In her chapter titled "Profit and Loss: The Mortality of the Digital Immortality Platforms," Debra Bassett examines this commodification in relation to the technological dependencies we develop as we care for and interact with a growing corpus of inherited posthumous data bodies.(1)

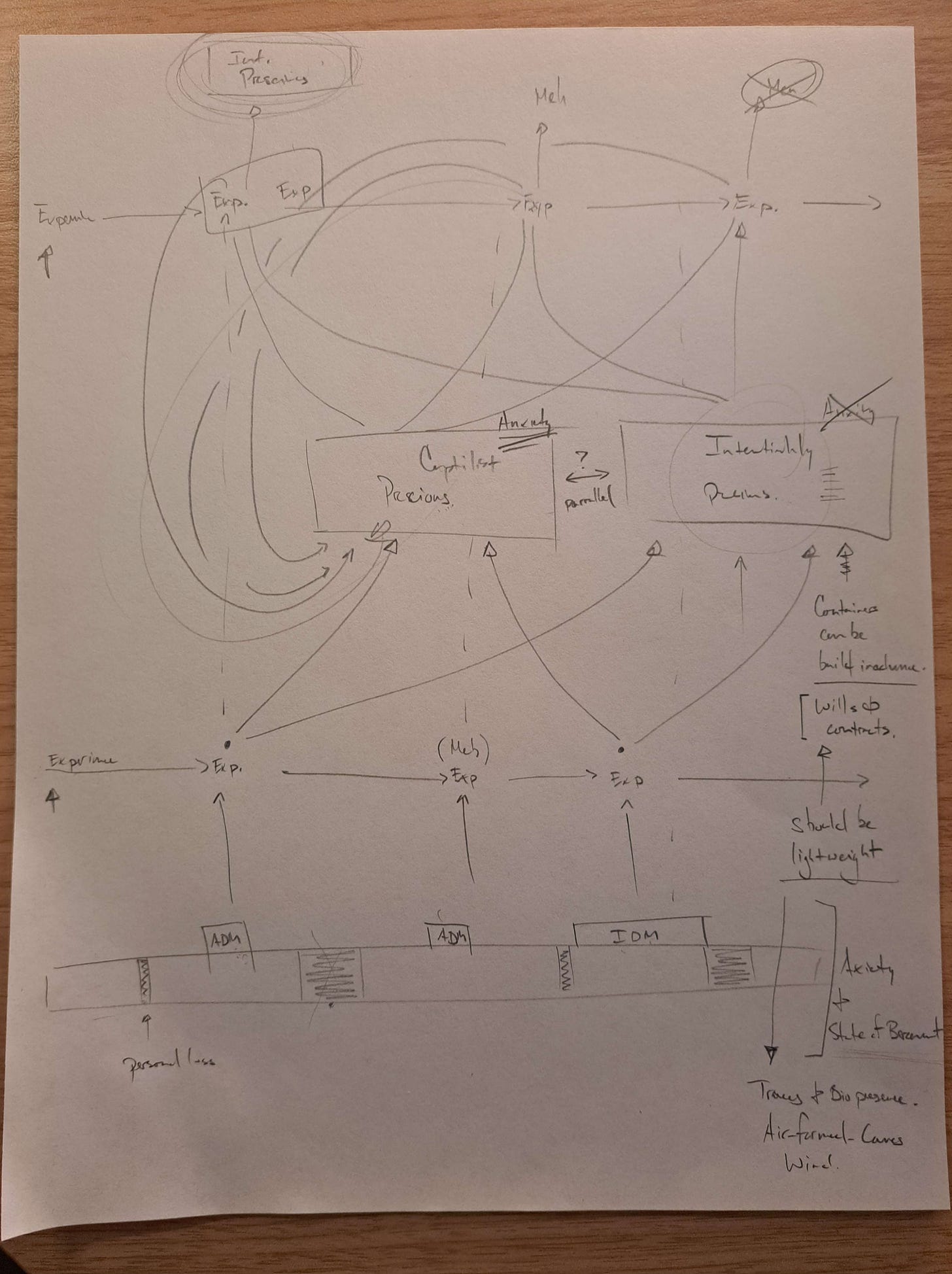

Bassett makes a distinction between two types of encounters with the afterlives of data: intentional and accidental. Example data includes: photos, voicemails, texts, and posts that are scattered across devices and websites that we access throughout our everyday lives. Intentional encounters with this data are those where select data has been prepared in advance and curated to represent a particular memory of the person the data indexes. Accidental encounters on the other hand account for the refuse of data we leave behind unaccounted for, never intended to serve as memorials. Basset interestingly frames these encounters through the prism of memory, referring to the data for each type of encounter as either “intentional digital memories” (IDM) or “accidental digital memories” (ADM).

There is a contradiction of sorts in the phrase “digital memories”. In particular the potential for transformation and archival are at odds with each other. That is, data can continue to be programmatically transformed in the afterlife leading to the formation of new and evolving memories, while archival imaginaries associated with the digital tend to imply perpetual preservation and unchanging essentialism. This tension is in fact constitutive of the socio-technical dependencies we form. By surfacing this tension, we are able to identify possible emotional responses and practices of precious-making that encounters with digital memories may provoke. These types of entanglements characterize the quality of our dependencies. And yet, through active disambiguation of the two, interventions are opened up to us that offer us a means for charting alternative paths for navigating our encounters with IDM and ADM.

We might think of our encounters with these data as digital containers, vessels into which we can pour meaning and form new memories; that is, ways of making the data precious. Most typically, this precious-making is shaped by the platforms and devices that host the data and define how we access and maintain our relationship with the dead.

It is in these cases where IDM and ADM are framed by an external, governing service provider that Bassett identifies a prevailing emotional tendency: anxiety. This is an invisible, latent anxiety that nevertheless builds with every constrained and commercially mediated interaction. This anxiety is only felt on those occasions where the reality of the dependency is surfaced by an interruption, real or imagined, and access to the digital containers holding our memories are severed. Two questions arise at this point: What dynamics animate this anxiety, and given that knowledge, how might we escape this commercially produced gravity of anxiety?

By making digital memories precious we expose ourselves to the risk of digital death, or what Bassett calls second loss. Bassett arrives at this concept by extending Patrick Stokes' concept of "second death". (2) A "second death" is a social death that occurs when an individual's name or memory is no longer known among the living. "Second loss", however, acknowledges that “second death” has been complicated by the digital. That is, the digital ushers in a seemingly never ending potential for recurrent second deaths: “those moments when the bereaved [lose] access to or lose the data of the dead." This perpetual state of bereavement, of infinitely recursive and unresolved loss is both the focus of this essay, and the obstacle to overcome in pursuit of an escape from second loss anxiety.

Perpetual Bereavement and The Grief Paradigm

The experience or even anticipation of a companion’s death powers a significant amount of ideas, behaviors and systems. It is a wholly human desire to bring our companions back, to keep them with us, to honor them. Our machines have extended this impulse by affording us continuous ways of producing digital data and seemingly endless storage capabilities. But, in an even more fundamental way, our machines facilitate digital instantiations of ourselves, ultimately capturing our digital selves within their silicon, mineral and metal frameworks. We become projected-beings, anesthetized by the immaterial space of the internet as François J. Bonnet describes us in After Death, (3) defined solely by the digital (non-)space around us. In other words, we are 'entombed' by machines, as Cade Diehm of the New Design Congress puts it (4), and also by capital.

In bereavement, we hold an impression of loss gathered from our experience of grief. If our digital debris, future ADM, is grounds for our own living-deadness, then every time we encounter our and other’s past digital bodies we are tasked with engaging in our digital condition and memories of anesthetization. In response to this condition, we are encouraged to produce ever more, to change it by force, and yet there is no moving beyond it. Locked in this perverse and ineffectual disinterment, we come to an understanding that grieving, the emotional and behavioral response to bereavement, has become the normative mode of interacting with machines. This is to say that our experience of being digital is to be subject to a new grief paradigm, that emotional response to the containers we use to make meaning of, to make precious, both ourselves and the dead.

Within our current grief paradigm, the ongoing condition of bereavement is hidden from ourselves, masked by behavioral impulses that emerge as a way of soothing the latent anxiety permeating our experience of digital environments. We are all too familiar with the sudden loss of our data through hard drive corruption, force-buried online profiles, or lost passwords to our digital storage, and yet each time the inevitability of bereavement reminds us of data’s impermanence and ephemerality, we double down – produce more data to fill the void, mask the inescapable state of loss.

From Bassett’s perspective, so long as the condition of bereavement is withdrawn from our attention, the potential for experiencing a second loss is near. Someone may have superficially processed their grief but bereavement was only lying in wait, to be activated again by the sudden loss of access to or corruption of data. Furthermore, it is at this point that we might be able to see the connection between bereavement and grief, and the practices of making containers for our precious remains and our emotional attachments to those containers. Bereavement begets making containers for precious-making, and grief emerges as a response to the quality of the containers we make and use.

At first, the identification of the bereaved subject as the person experiencing grief from the second loss of a companion's data feels appropriate, but when considered in the context of what Bassett is addressing - sudden loss of access to data of the dead - it could be seen more broadly. As our personalities fragment into various locations on the internet, we find ourselves bonding with entities we wouldn't expect to feel connection with. Text messages with a friend, saved video game data, profiles and para-social bonds on whatever social media platform is in vogue, even bank accounts. If we consider what drives us to check and engage with these entities multiple times a day - they provide a source of security and connection - we already know that losing access would feel destabilizing.

We can extend Bassett's definition even further backwards to say that this state of bereavement is conditioned on already having experienced a first loss online. This 'first loss' can be located in what Sherry Turkle identifies in The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit. (5) In it, she states:

"The socially shared activity of computer programming and hardware tinkering has been displaced by playing games, participation in online chat and blogs, and using applications software out of the box"

She elaborates on her uneasiness of this displacement:

"Citizenship in a culture of simulation requires that you know how to rewrite the rules... However, as I meet professionals in all of these fields who move easily within their computational systems and yet feel constrained by them, trapped by their systems' unseen limitations and unknown assumptions, I feel continued concern. Are the new generations of simulation consumers reminiscent of people who can pronounce the words in a book but don't understand what they mean?"

Turkle asserts that the loss of transparency in the tools we use to create data means a political loss of authorship, handed over to service providers that now control these programs and make the rules. In the space of this first loss, we start from a place of fundamental misunderstanding, confusion even, and are forced to make meaning from what has been provided for us when a second loss occurs. Often we push forward with the tools we have, projecting more meaning and more value onto them. If we are compelled to seek out an understanding, we must forge new tools for crafting and regulating bereavement, for making the remains of what we have lost precious.

Archival Imaginaries and Digital Essentialism

Let’s momentarily return to the idea of archival imaginaries to excavate ways of forming new containers and practices around those vessels for precious-making. Basset’s notion of the ‘digital dasein’ in particular is a useful starting point for thinking through these imaginaries. Bassett writes, "Within this digital dasein, the essence of the dead is digitally embodied in a form of posthumous essentialism and the idea that the essence of the dead continues to be 'somewhere' can bring comfort to the bereaved who are using digital memories and messages as important tools for their grief."

For digital memories to be experienced as a form of posthumous essentialism suggests that as bereaved individuals we are not expecting that the data will change, that the pictures and posts will remain where they are, in that elusive 'somewhere' architected by the service providers who have created the posting structure and profile template within the platform’s system. Because we're at the mercy of the construction and location of this 'somewhere', subject to our initial “first loss”, and thus how the data is manipulated and embedded, the second loss of the digital memories can feel more profoundly destabilizing than the initial biological death. The essentialism of archival imaginaries has rendered the data bodies we care for brittle and precarious. Whereas we might anticipate the loss of a loved one in their biological state, we are preemptively stripped of anticipative capacity or intentional processing by the ways service providers obscure and commoditize the dead.

The moment of that second loss, the moment that the relationship between digital and archival essentialism is ruptured, punctures a hole in the immortal web of online time. The physical and the metaphysical are collapsed. Are the digital memories gone forever or gone to a place we cannot access? This inability to intentionally part with ADM and IDM serves as an example for what we might look for if we are to make our own containers for making our digital memories precious: established rites of passage for navigating our relationship to the digital data of the deceased.

Data Replaces the Soul

What rites might help us navigate this collapse? Spirituality offers a way of understanding the temporality of the deceased as it passes from the physical into the immaterial and the pain associated with second losses of the newly immaterial.

The practice of secondary burial rites are a formalized process for safely moving the dead from the physical into the astral realm, transforming the non-material component of the dead into a soul, and restoring social order to their community by disentangling the soul of the dead from the bodies of the living, on their own terms. In practice, secondary burial rites are given to a body after its initial burial, after its bones have withered and dried, when it can then be relocated to a final resting place so that the spirit may complete its journey. This tradition can be understood in the most general terms as a way to reunite the soul of the dead with their ancestors in the spirit realm. These death rites are traditionally practiced by indigenous cultures throughout the world and are structured by animism, a belief system that attributes a spiritual essence to all things. This attribution is reflected in our own entanglements with our technological dependencies, formed through systems that render the material immaterial as quickly as possible, essentializing the dead and surrendering the control of precious-making on our own terms.

Secondary burial rituals typically originate from a fear of the corpse, so a quick, first burial of the corpse is performed to prevent further distress by the material loss. This fear is also present in non-animistic cultures where the fear of the corpse is associated with health concerns, resulting in a bureaucratic funeral industry that mirrors the ways in which the dead are immediately rendered immaterial, turning them into abstract tokens of exchange in a system that that capitalizes on abstraction and marginalizes their presence into funeral sites further from social presence (6). The difference in anamistic practices though is the intentional renegotiation of the dead’s immaterial essence by the community in the space between a first and second burial. Interestingly, certain animistic cultures have a different attitude toward the remaining non-material component of the dead than our own association with its immortality. Instead, the non-material component is considered spiritual but not yet viewed as a soul, nor is it understood to be everlasting. Sociologist Robert Hertz first took note of this nuance in his essay "A Contribution to the Study of the Collective Representation of Death" (7)

“This representation is linked to a well-known belief: to make an object or a living being pass from this world into the next, to free or to create the soul, it must be destroyed… as the visible object vanishes it is reconstructed in the beyond, transformed to a greater or lesser degree. The same belief applies to the body of the deceased.”

Our own implicit belief in the immortality of our non-materiality is inherited from capitalism. Archival artifacts have a way of being rendered into commodities. Instead of developing practices that would allow us to observe decaying artifacts, if we encounter data bodies we want to make precious, our impulse is to view them through archival imaginaries of digital essentialism. We hurriedly submit our artifacts, our IDM, and even sometimes ADM, to a service provider and begin the ritual of sending payment and proof of kinship in order to maintain access.

Similarly, our ‘renegotiation period’ is captured and capitalized by nascent AI projects which seek to fulfill their promise that the dead might live on in the digital afterlife, or the techno-astral plane. This is the digital imaginary of data transformation, currently framed as chatbots with the dead, otherwise known as thantabots, however still governed by services providers who will determine the contexts for the collective representations that these bots exist within, the constraints on their digital afterlife, and how future generations will interact with this preserved data.

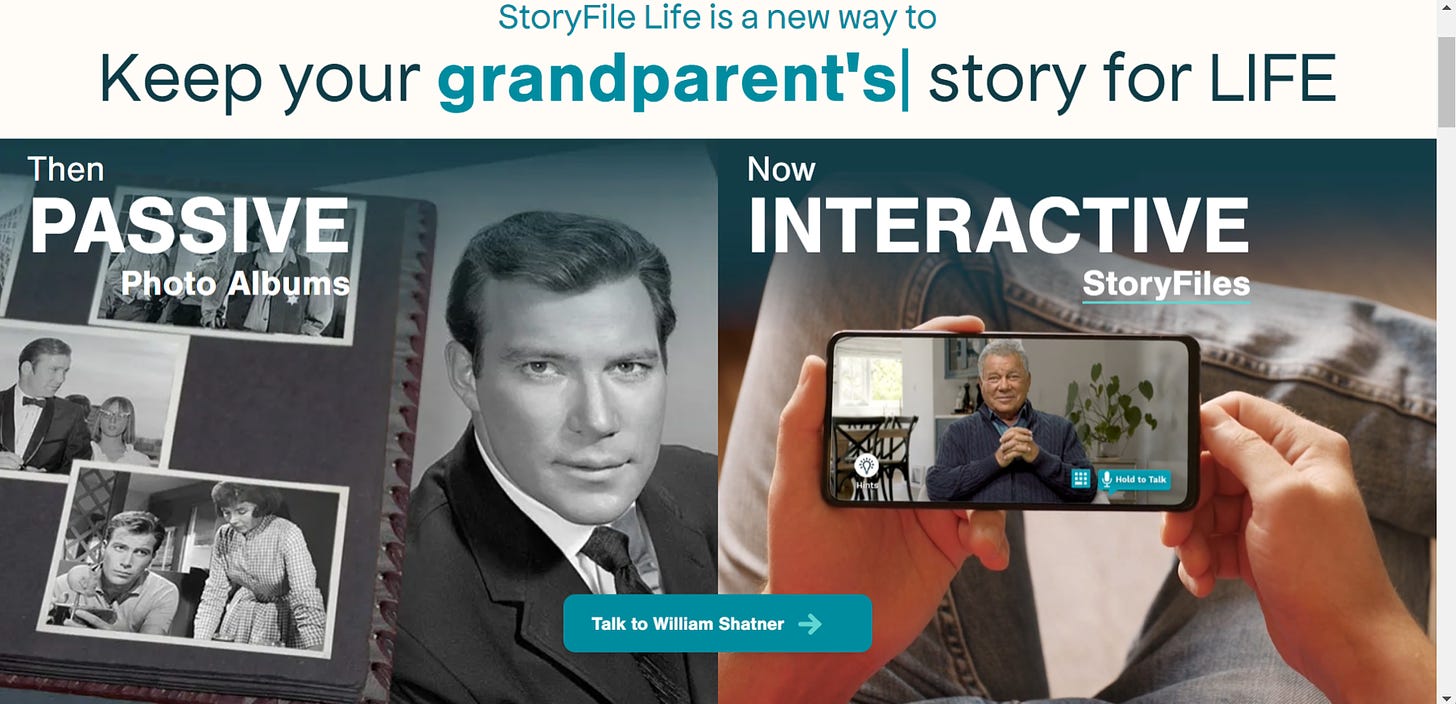

Consider two contrasting examples where the nature of these constraints are illustrated. StoryFile Memories is a cloud-based file storage system in which people can upload all manner of digital artifacts - images, video and sound recording - to become an interactive AI of their "authentic self" intended to live after death and communicate with the bereaved. (8) With plans ranging from $1 per question to a one-time, all-access price of $499, users can answer from a bank of over 1600 predetermined questions about their life and experiences. Their answers are then transformed by StoryFile's proprietary conversational AI which can then be interacted with. All plans currently offer unlimited conversations with the digitally transformed.

In contrast, Project December is trained on data intentionally input by the bereaved about the dead, but places other constraints on the type of data used to construct the thantabot. (9) Users are given the opportunity to recall memories of the dead in the form of their own remembrances, instead of using the data artifacts left behind, thus creating a more personally crafted entity to interact with. This process is akin to the renegotiation process described above, though framed in the logic of individualism rather than collective processing. However, other forms of constraints are placed on the construction process, with personality traits being defined through predetermined binaries, and limits on interaction time. Project December is a paid service offered by OpenAi. The website states that for $10, “your conversation will included over 100 back-and-forth exchanges and will last an hour or more, depending on how quickly you respond and how you spread your conversation out over time”

In both cases, we have thantabots and digitally reconstructed afterlives that we both interact with and also risk having intrude into or infect our own selves. All of these are more palatable terms for what Bassett calls "digital zombies" to describe the dead online as 'resurrected, reanimated, and socially active', digital artifacts that transcend their digital essentialism and become fully or partially alive in the online afterlife. But it's Bassett's digital zombie that most closely resembles animistic representations of the dead.

In Celebrations of Death: The Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual, (10) authors Peter Metcalf and Richard Huntington observe several indigenous animistic cultures in Southeast Asia that practice secondary burial. The Berawan of northern Borneo have a captivating belief for its purpose: souls may wander far from their human body during illness or at death, and upon return to their body, find it has greatly decomposed. They are unable to reenter and revive their body; to do so would create a monster. Thus, a ceremony must be performed to summon and guide the spirit properly into the land of the dead, to be recognized by the ancestors as a 'beautiful spirit'.

The anxiety Bassett writes at length about is the monster taking shape for the bereaved subject. It could be in the form of the digitally enduring memory itself appearing at an inappropriate or unexpected moment, or more directly to her text, as a non-entity: a disappeared artifact now impossibly gone from the 'digital dasein' where its essence was comfortably experienced in programmed environments.

What surfaces in this initial review of AI projects are the ways in which they serve as an evolution of the digital containers we use for precious-making. In other words, they represent a step towards the conceptualization of digital secondary burial sites for sending our data bodies into the techno-astral plane, and articulate the parameters used to define the rites associated with that passage. However, in both cases, we are resorting to service providers that continue to accelerate the commodification of our digital afterlives. The question that remains for us is whether the data arrives in this location transformed after a period of renegotiation or if it arrives unprocessed, still bound to and feeding into our anxieties. This remains an open question. As exemplified here, spiritual, non-digital perspectives give us tools for understanding the socio-technical rituals and dependencies that we are engaged in. By continuing to pursue these lines of thought, we develop new ways of framing our interactions with the dead online, and may find pathways for breaking our calcified archival imaginaries and reimagine new ways of living with the data bodies we construct, inhabit, and inherit.

Bibliography:

Bassett, Debra. "Profit and Loss: The Mortality of the Digital Immortality Platforms." Digital Afterlife: Death Matters in a Digital Age, edited by Maggi Savin-Baden and Victoria Mason-Robbie, Routledge, 2021, pp. 78-96.

Stokes, Patrick. "The State of Postmortem Privacy: Respect, Memory, and the 'Right to be Forgotten'." Ethics and Information Technology, vol. 16, no. 4, 2014, pp. 297-309. doi: 10.1007/s10676-014-9344-0.

Bonnet, François J. After Death. Urbanomic, 2018.

Diehm, Cade. Comment on the New Models server. Discord, 3 Mar. 2023.

Turkle, Sherry. The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit. Twentieth Anniversary Edition, MIT Press, 2005.

Krupar, Shiloh R. "Green Death: Sustainability and the Administration of the Dead." Cultural Geographies, vol. 25, no. 2, 2018, pp. 267-284. doi: 10.1177/1474474017732977

Hertz, Robert. "A Contribution to the Study of the Collective Representation of Death." Death and the Right Hand, translated by Rodney Needham, Free Press, 1960, pp. 1-86.

StoryFile: Revolutionary Conversational Video." StoryFile, https://storyfile.com/

Project December." Project December, https://projectdecember.net/

Metcalf, Peter, and Richard Huntington. Celebrations of Death: The Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual. 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 1991.

🪦💾

🫡